Most people never question the idea that carbohydrates are a metabolic requirement. We’re told the body runs on glucose, the brain needs sugar, and removing carbs inevitably leads to fatigue and poor health. When energy dips or concentration falters, it’s taken as confirmation.

What’s rarely explored is whether those early effects reflect true biological dependence—or simply a system unaccustomed to switching fuels. Fortunately, the human body is more adaptable than that.

When carbohydrates are removed from the diet, the body does not run out of energy—it changes how energy is produced and used. Blood sugar and insulin levels shift, stored fuel is mobilized, and metabolic pathways that are largely unused in modern diets become active again. What follows is not a failure of metabolism, but a transition.

Much of the confusion around low-carbohydrate diets comes from misunderstanding this process. Temporary adjustment is often mistaken for long-term dysfunction, and glucose is frequently treated as the only fuel the body can use. In reality, dietary carbohydrates are just one way the body can meet its energy needs.

Humans evolved with the ability to switch between fuel sources depending on availability. In a world of constant carbohydrate intake, that flexibility is rarely called upon, which makes the experience of reducing carbs feel unfamiliar—and sometimes uncomfortable at first. Unfamiliar, however, does not mean unsafe.

This article explores what actually happens inside the body when carbohydrates are reduced or removed. Not as a diet prescription, and not as an argument against carbohydrates, but as a clear physiological explanation of how the body adapts when one fuel source is no longer dominant.

What Carbohydrates Normally Do in the Body

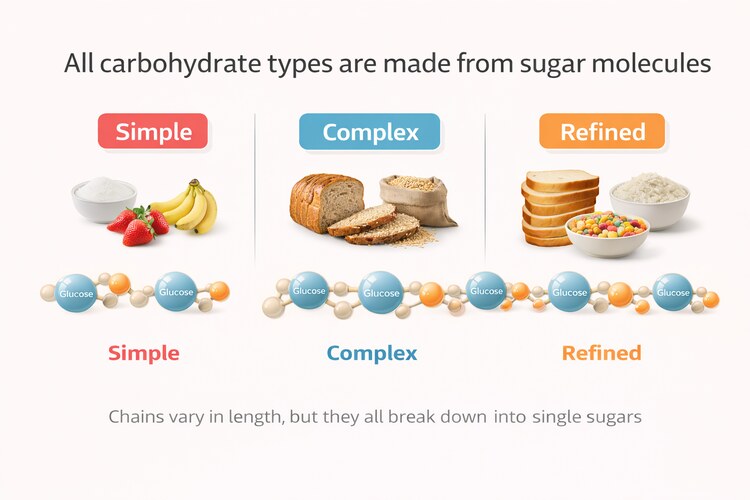

Carbohydrates themselves are not fuel in the form the body can directly use. They are chains of sugar molecules that must first be broken down into simple sugars—primarily glucose, along with smaller amounts of fructose and galactose. Of these, glucose plays the central role in human metabolism because it circulates in the bloodstream and must be tightly regulated.

See this article here for a more in-depth look at the roles of glucose and fat as different energy supplies.

Once absorbed, glucose enters the bloodstream and must be tightly regulated. While glucose is a useful fuel, elevated blood sugar is not benign. When glucose lingers in circulation, it contributes to oxidative stress and cellular damage, which is why the body treats its clearance as urgent.

Rising blood sugar triggers the release of insulin, which directs glucose into cells for immediate use or storage. Some of this glucose is burned right away to meet energy needs. The remainder is stored as glycogen, primarily in the liver and skeletal muscle, where it serves as a short-term energy reserve.

These glycogen stores are small and short-lived by design. The liver typically holds enough glycogen to maintain blood sugar for roughly 12 to 24 hours in the absence of food. Muscle glycogen varies with body size and activity but is generally sufficient for hours of moderate to intense exercise, not days of energy supply. Compared to the body’s fat reserves, glycogen is a limited, temporary buffer.

Because glucose must be cleared quickly and because it is easy for cells to use, the presence of carbohydrates pushes metabolism toward a glucose-dominant state. Fat breakdown and ketone production are downregulated—not because they are inferior fuel sources, but because they are unnecessary while glucose is abundant and being actively managed.

This metabolic prioritization is often mistaken for dependence. In reality, it reflects availability and safety, not exclusivity. When glucose is constantly supplied, the body uses it. When it is not, the body shifts to other fuels that are already built into human physiology.

For details on how exactly the body operates when eating carbohydrates, see this article here.

The First 24–72 Hours Without Carbohydrates

When carbohydrates are removed from the diet, the body enters a short period of metabolic adjustment rather than immediate adaptation. The goal during this phase is not to switch fuel systems overnight, but to keep blood glucose within a narrow, safe range while alternative pathways begin to increase. As with most aspects of metabolism, the priority is efficiency and stability, not speed.

Stored liver glycogen plays a central role in this process. Its function is to release glucose into the bloodstream to maintain stable blood sugar between meals. When dietary carbohydrates are no longer available, liver glycogen is steadily drawn down, with levels typically falling substantially over the first 12 to 24 hours depending on prior intake and activity. These stores do not disappear entirely, however. Even without carbohydrates, the liver continues to replenish small amounts of glycogen using internally produced glucose, maintaining a reduced but dynamic buffer rather than a full reserve.

As glycogen availability declines, insulin levels fall and the hormonal environment shifts. Lower insulin removes the signal to store incoming energy and allows stored energy to be released instead. This marks the point at which fat tissue begins to contribute more meaningfully to energy supply, setting the stage for the broader metabolic transition that follows.

Fat Utilization

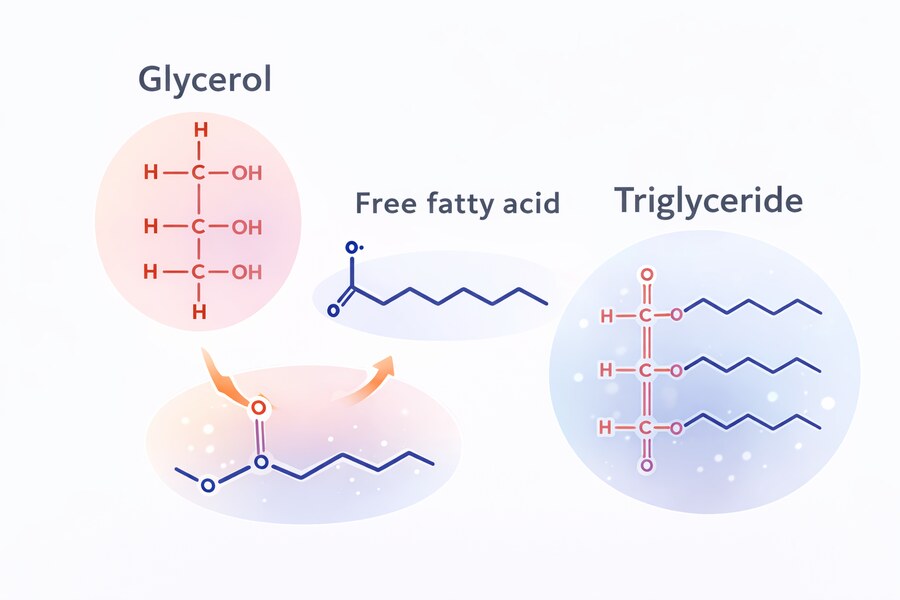

Body fat is stored primarily as triglycerides—large molecules made up of three fatty acids bound to a glycerol backbone. These storage molecules cannot be used directly by most tissues, so when insulin levels fall, the inhibitory signal that suppresses fat breakdown is removed, allowing counter-regulatory hormones such as glucagon and adrenaline to activate fat metabolism.

In response, fat cells break triglycerides apart, releasing free fatty acids into the bloodstream, where they can be used by tissues such as muscle, heart, and liver for energy. The glycerol released in this process is sent to the liver, where it contributes to glucose production through gluconeogenesis.

These fatty acids are a normal, benign fuel source. Many tissues—including skeletal muscle, heart muscle, and much of the liver—can use fatty acids directly for energy. This process is not harmful or stressful in itself; it is a routine part of human metabolism that occurs during fasting, between meals, and overnight.

At the same time, the liver begins converting some of these fatty acids into ketone bodies, commonly referred to as ketones.

Ketone Release

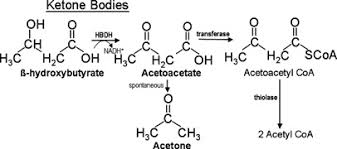

Ketones are small, water-soluble molecules produced by the liver from fat-derived fatty acids. Their role is to act as an alternative fuel that can circulate easily in the blood and cross into tissues that cannot use fatty acids directly, the most important of which is the brain.

Fatty acids are too large to cross the blood–brain barrier efficiently, which means the brain cannot run directly on fat. Ketones solve this problem. They provide a fat-derived fuel that the brain can use, reducing its reliance on glucose when carbohydrate intake is low.

Ketone production begins to rise within the first couple of days without carbohydrates, but it remains relatively modest at this stage. The body is still in transition, not yet fully adapted to relying on ketones as a major fuel source.

Glucose Still Matters

Even without dietary carbohydrates, the body does not lose its ability to supply glucose. Certain tissues continue to require it. Red blood cells, which lack mitochondria, rely exclusively on glucose, and small portions of the brain and certain cells in the kidney and immune system also depend on it.

To meet these needs, the liver—and to a lesser extent the kidneys—produces glucose internally through a process called gluconeogenesis, using non-carbohydrate sources such as amino acids, lactate, and the glycerol released when triglycerides are broken down.

Crucially, as ketone availability increases, overall glucose demand falls. In a carbohydrate-fed state, studies have found that the brain typically consumes between 110-130 grams of glucose per day. During full ketosis, this requirement drops substantially as ketones supply the majority of its energy needs, with studies showing the brain using around 40 grams per day, with the ketones supplying the remaining 60-70% of energy.

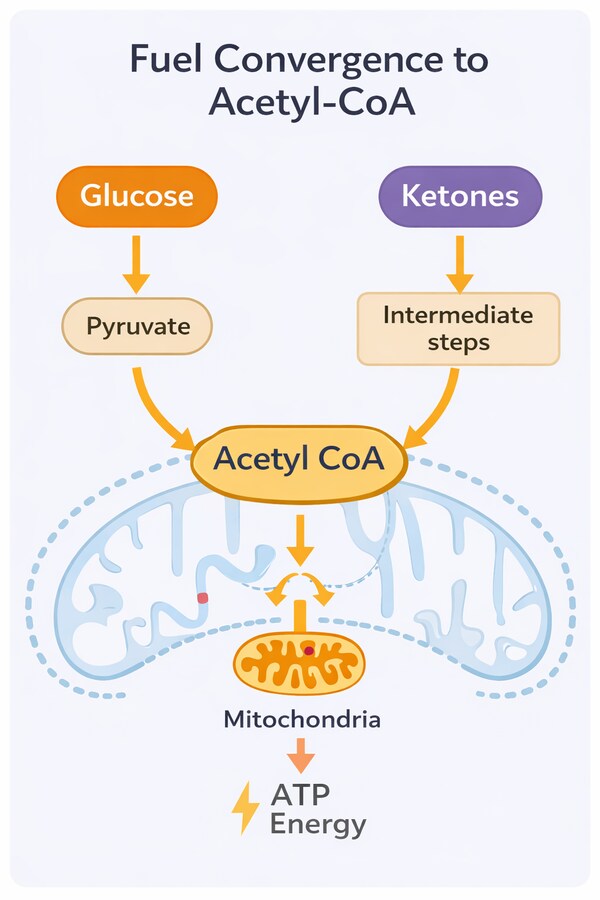

This does not reflect a shortage of usable energy. Both glucose and ketones are ultimately converted into acetyl-CoA, the common fuel that enters the mitochondria to produce ATP. The shift therefore represents a change in fuel delivery and efficiency, not a decline in energy availability or brain function.

Gluconeogenesis is not an emergency backup mechanism. It is always active to some degree, even in people eating carbohydrates, and simply adjusts to match demand. Under normal conditions, the body can produce on the order of 150–200 grams of glucose per day—enough to meet the needs of glucose-dependent tissues while the rest of the body increasingly relies on fat and ketones.

This level of glucose production is not merely sufficient for survival. Once adaptation has occurred, it supports normal physiological function, including tissue repair, immune activity, and brain metabolism.

Why This Phase Can Feel Difficult

During the first 24–72 hours, fuel systems are still realigning. Glycogen levels are declining, insulin is falling, electrolyte and water loss increases, and ketone production has not yet fully scaled to meet demand. The size of this adjustment depends heavily on how carbohydrate-dependent the metabolism was to begin with.

For individuals consuming the commonly recommended high-carbohydrate intakes—often 200 to 300 grams per day—the drop in glucose availability is large and abrupt. Fat oxidation and ketone use may lag behind, creating a temporary mismatch that produces symptoms such as fatigue, headache, lightheadedness, or mental fog.

By contrast, those already eating fewer carbohydrates—particularly those following low-carb or ketogenic patterns—experience a much smaller shift. Insulin is already low, fat metabolism is active, and ketone production is partially established. In metabolically flexible individuals, the transition can be subtle or barely noticeable.

Metabolic Flexibility vs Metabolic Inflexibility – key Physiological Differences

| Feature | Metabolically Flexible | Metabolically Inflexible |

| Baseline fuel use | Uses glucose and fat interchangeably | Relies predominantly on glucose |

| Insulin levels | Low to moderate; fall readily | Chronically elevated; slower to fall |

| Fat oxidation | Rapidly increases when carbs are reduced | Slow to upregulate |

| Ketone production | Rises quickly and efficiently | Delayed and blunted initially |

| Brain fuel switching | Smooth transition to ketone use | Slower transition; temporary mismatch |

| Gluconeogenesis | Matches reduced glucose demand | Must scale rapidly to meet higher demand |

| Long-term adaptability | Stable energy across fuel states | Struggles outside glucose-dominant state |

In all cases, these effects reflect a temporary delay in fuel switching, not a lack of usable energy or a failure of metabolism. As fat oxidation and ketone utilization increase and electrolyte balance stabilizes, the system settles into a new equilibrium.

The Metabolic Shift: From Glucose to Fat

After the initial adjustment period—typically spanning the first several days for metabolically flexible people, or as long as two weeks for metabolically inflexible people—the body begins to reorganize how it produces and uses energy. By this point, short-term glucose reserves have been depleted, insulin levels remain low, and fat-derived fuels are consistently available. What follows is no longer a response to carbohydrate absence, but a new metabolic baseline.

At this stage, fat is no longer released merely to compensate for falling blood glucose. It becomes the primary fuel source for most tissues, supported by rising ketone production and improved fat-oxidation capacity.

How Different Tissues Adapt

Skeletal muscle is among the first tissues to adapt. As enzymes involved in fat oxidation increase, muscle fibers become more efficient at using fatty acids for energy. This reduces their reliance on glucose and allows muscle glycogen to be conserved for brief, high-intensity activity rather than routine energy needs. In keto-adapted individuals, studies have shown that peak rates of fat oxidation can more than double compared with carbohydrate-fed athletes, reflecting a substantial shift in muscle fuel utilization.

The heart undergoes one of the most pronounced shifts. Cardiac muscle has a high, continuous energy demand and a dense mitochondrial network, and under normal physiological conditions it derives much of its energy from fatty acid oxidation. This preference—documented across decades of human and animal studies—reflects efficiency rather than stress. In low-insulin and low-carbohydrate states, the heart readily increases use of both fatty acids and ketones as stable, high-yield fuel sources, underscoring that ketone metabolism is a normal and well-tolerated component of human energy physiology rather than an emergency response.

The liver continues to function as the central metabolic coordinator. Fatty acids arriving from adipose tissue are either used directly for energy or converted into ketone bodies, which are released into the bloodstream to supply other organs. Ketone production becomes steadier and more closely matched to demand, rather than rising sharply in response to falling glucose as it does early in the transition.

Brain Adaptation and Reduced Glucose Demand

One of the most meaningful changes occurs in the brain. During the early days without carbohydrates, the brain still depends heavily on glucose, which is why cognitive symptoms like brain fog are commonly reported during the transition phase. As ketone availability increases, however, the brain progressively increases ketone uptake and utilization.

Over time, ketones can supply a substantial portion of the brain’s energy needs, significantly reducing—but not eliminating—its requirement for glucose. This lowers the burden on gluconeogenesis and decreases the need to continually convert protein and other substrates into glucose.

This adaptation is not merely sufficient; it is metabolically efficient. Ketones provide a stable energy source with less fluctuation than glucose, which helps explain why mental energy often becomes more consistent once adaptation is complete.

Energy Stability and Metabolic Efficiency

As fat oxidation becomes the dominant energy pathway, overall energy availability becomes less dependent on meal timing. Fat stores are large and continuously accessible, allowing energy production to remain stable across long periods without food.

At the cellular level, mitochondria adapt by upregulating enzymes involved in fat metabolism and ketone utilization. This shift supports steady ATP production and reduces reliance on rapid changes in blood sugar. Hunger patterns often change as a result—not because appetite is suppressed, but because energy availability becomes more consistent.

Ketones as More Than Fuel

Ketones do more than provide energy. They also act as signaling molecules that influence key regulatory pathways involved in growth, repair, and cellular maintenance.

In low-insulin, low-carbohydrate states, signaling through pathways such as mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin) tends to decrease, while processes associated with cellular cleanup and repair—such as autophagy—are upregulated. This reflects a broader shift from a growth-focused metabolic state, driven by frequent nutrient availability, toward a maintenance and repair-oriented state.

These signaling effects are an active area of research, but they help explain why the metabolic shift involves more than simply replacing one fuel with another. The body is not just changing what it burns—it is changing how it allocates resources between growth, storage, and repair.

Glucose-Dominant vs Ketone-Dominant Metabolic Signaling

| Hormone / Pathway | Glucose-Dominant State | Ketone-Dominant State | Functional Role |

| Insulin | ↑ Elevated | ↓ Low | Drives glucose uptake, storage, and anabolic signaling |

| Glucagon | ↓ Suppressed | ↑ Elevated | Mobilizes stored energy; supports gluconeogenesis |

| mTOR | ↑ Activated | ↓ Suppressed | Growth, protein synthesis, cell proliferation |

| AMPK | ↓ Low activity | ↑ Activated | Energy sensing; promotes fat oxidation and repair |

| Lipolysis | ↓ Inhibited | ↑ Upregulated | Release of fatty acids from adipose tissue |

| Fat oxidation | ↓ Reduced | ↑ Increased | Primary fuel use from fatty acids |

| Autophagy | ↓ Suppressed | ↑ Enhanced | Cellular cleanup and maintenance |

| Inflammatory signaling | ↑ Often higher | ↓ Often reduced | Systemic inflammatory tone |

| IGF-1 signaling | ↑ Higher | ↓ Lower | Growth and anabolic signaling |

None of this implies that carbohydrates are inherently harmful or that growth-oriented metabolism is undesirable. It illustrates that human metabolism is flexible, capable of operating in different modes depending on fuel availability.

By this stage, the body is no longer merely tolerating the absence of carbohydrates. It has reorganized itself around a different, fully functional metabolic strategy.

For more details about the changes and potential benefits from ketosis and fasted states, see this article here.

Short-Term Effects During the Transition Phase

In a metabolically healthy body, fuel use is flexible. Glucose, fatty acids, and ketones are continually increased or decreased based on availability, demand, and efficiency. The body does not “commit” to a single fuel source—it shifts between them as conditions change.

In modern diets, however, this flexibility is often underused. Constant carbohydrate intake, frequent eating, and chronically elevated insulin keep metabolism locked in a glucose-dominant state. When carbohydrates are suddenly reduced, the machinery required to switch fuels may be slow to respond.

This difference helps explain why the transition away from carbohydrates feels effortless for some people and difficult for others.

Metabolic Inflexibility and the Transition Phase

When metabolic flexibility is reduced, the body is slower to increase fat oxidation and ketone production as glucose availability declines. Glycogen is falling, insulin is low, but alternative fuel pathways are not yet fully active. The result is a temporary gap between energy demand and energy delivery.

This gap—not a true lack of energy—is what produces many of the short-term symptoms often referred to as “keto flu.” Fatigue, mental fog, headaches, and weakness reflect delayed fuel switching rather than metabolic harm.

See here for a detailed look at exactly what is “keto-flu” and how it can best be avoided when transitioning to a low carbohydrate diet.

Longer-Term Adaptation (Weeks to Months)

As the weeks progress, the metabolic changes initiated during the transition phase become more stable and efficient. Fat oxidation and ketone utilization are no longer reactive responses to falling glucose but are fully integrated into everyday energy production. At this stage, the body is not simply coping without carbohydrates—it is operating comfortably in a different metabolic mode.

Restored Energy Stability

One of the most consistent changes people notice over time is greater stability in energy levels. With fat and ketones supplying the majority of baseline energy needs, energy availability becomes less dependent on recent meals. Large swings in blood sugar are reduced, and the frequent cycles of hunger and fatigue that accompany glucose-heavy diets often diminish.

This does not mean energy is constantly elevated. Rather, it becomes more predictable. Physical and mental effort draw from a large, continuously accessible fuel supply, rather than from short-lived glucose spikes.

Improved Fuel Efficiency and Flexibility

At the cellular level, mitochondria adapt to favor fat-derived fuels. Enzymes involved in fatty acid oxidation and ketone metabolism are upregulated, while reliance on rapid glucose turnover decreases. This improves overall metabolic efficiency and reduces the need for constant fuel intake.

Crucially, this adaptation does not eliminate the body’s ability to use glucose. Metabolic flexibility improves, allowing glucose to be used effectively when it is available or needed—such as during intense physical activity—without making it the default fuel at all times.

Appetite Regulation and Satiety

As insulin signaling stabilizes and energy delivery becomes more consistent, appetite cues tend to normalize. Meals are often driven more by physiological needs than by rapid fluctuations in blood sugar. Many people find they can go longer between meals without discomfort, not because hunger is suppressed, but because energy availability is steady.

This shift is a downstream effect of metabolic adaptation, not a conscious effort to eat less.

Physical Performance Over Time

Endurance and low- to moderate-intensity activity often feel easier as fat oxidation improves. We already saw how the FASTER study found peak fat oxidation 2.3-fold higher in long-term low-carb athletes. Similarly, a randomized crossover study of competitive powerlifting and Olympic weightlifting athletes, three months on a ketogenic diet (≤50 g carbohydrate/day) reduced body mass but did not impair maximal lifting performance compared with a high-carbohydrate diet.

Activities that rely heavily on rapid glucose turnover—such as short, high-intensity bursts—may require more time to fully adapt or may perform best with some carbohydrate availability. This pattern was already observed in classic work by Phinney and colleagues, who studied trained individuals after four weeks of nutritional ketosis. In that study, endurance at moderate intensities was preserved despite increased reliance on fat oxidation, while capacity for high-intensity exercise declined alongside lower muscle glycogen levels. Together, these findings suggest that fat-based metabolism readily supports sustained work, but activities dependent on rapid glycolytic flux may remain constrained by limited glucose availability.

This highlights an important point: adaptation does not create a single “optimal” fuel strategy for all activities. It expands the body’s capacity to match fuel use to demand.

A Stable, Sustainable State

By this stage, most of the symptoms associated with early carbohydrate reduction have resolved. Electrolyte balance stabilizes, cognitive energy improves, and physical function normalizes. The body has regained the ability to move smoothly between fuels rather than remaining locked into a glucose-dependent pattern.

This longer-term state is not fragile. It reflects a metabolically flexible system capable of functioning across a range of dietary conditions.

For more details on the potential longer-term benefits of the ketogenic diet, see this article here.

Potential Downsides to Low-Carb Diets

While the human body is capable of adapting to low-carbohydrate conditions, that does not mean this metabolic state is optimal for everyone, in every context, at all times. Metabolic flexibility works in both directions, and there are situations where limiting carbohydrates may be unnecessary, counterproductive, or require careful modification.

High-Intensity and Glycolytic Demands

Certain forms of physical activity rely heavily on rapid glucose availability. Short, explosive efforts—such as sprinting, repeated maximal lifting, or high-intensity intervals—place a high demand on muscle glycogen. While some adaptation can occur over time, performance in these contexts may remain constrained without adequate carbohydrate availability.

This does not indicate a metabolic flaw. It reflects the reality that different fuels excel under different demands, and in these cases, strategic carbohydrate intake may support performance without negating broader metabolic health.

For most people, however, these limitations are unlikely to be relevant. The majority are not training at the absolute limits of strength or endurance where small differences in fuel availability determine outcomes. Such constraints primarily affect highly trained athletes operating near their physiological ceiling, rather than individuals engaging in general fitness, recreational sport, or everyday physical activity.

Thyroid Signaling and Energy Regulation

In some individuals, particularly those combining low carbohydrate intake with aggressive calorie restriction or high stress, thyroid hormone signaling may shift. This is often reflected in changes to circulating T3 levels, which play a role in regulating metabolic rate.

Importantly, this is not a universal outcome and is heavily context-dependent. Adequate total energy intake, sufficient protein, and stress management appear to play a larger role than carbohydrate intake alone. Still, for some people, prolonged very-low-carb intake may require closer attention to overall energy balance.

Individual Variation and Metabolic History

Not all metabolisms respond identically. People with long-standing metabolic dysfunction may initially benefit from carbohydrate restriction but later find that moderate reintroduction improves tolerance, performance, or well-being. Others may struggle with low-carb diets due to genetic factors, activity levels, or personal physiology.

Adaptation is also influenced by metabolic history. Individuals who have spent years in a glucose-dominant state may require more time to regain flexibility—or may prefer approaches that encourage gradual switching rather than strict elimination.

What This Means for Modern Diets

What happens when carbohydrates are removed is not metabolic failure, but metabolic reorganization. The body does not lose its ability to produce energy—it shifts how energy is sourced, regulated, and delivered. Glucose use declines, fat and ketone use increase, and hormonal signals adjust accordingly. For many, this process reveals a capacity that modern eating patterns rarely allow to surface.

Much of the discomfort associated with low-carbohydrate diets arises not from carbohydrate absence itself, but from metabolic inflexibility—the result of long-term reliance on a single fuel system. When the body relearns how to switch between fuels efficiently, energy delivery stabilizes and many of the feared consequences fail to materialize.

At the same time, this does not mean carbohydrates are inherently harmful or universally unnecessary. Different fuels serve different purposes, and metabolic health is defined by flexibility, not exclusion. A system that can use glucose when needed, fat when appropriate, and ketones when advantageous is more resilient than one locked into any single mode.

In a food environment defined by constant availability and frequent eating, understanding how the body responds when carbohydrates are reduced provides useful perspective. It challenges the idea that glucose is the only viable fuel and reframes dietary choices around physiology rather than dogma.

The question is not whether carbohydrates should be eliminated, but whether the body is capable of functioning well without relying on them at all times. That capacity—more than any specific macronutrient target—is the foundation of metabolic health.

FAQs

What happens to your body when you stop eating carbohydrates?

When carbohydrates are removed, insulin levels fall and stored fat is released for energy. The body gradually shifts from relying on glucose to burning fatty acids and producing ketones. During this transition, some people experience temporary symptoms as metabolism adapts, but energy production is maintained once adaptation occurs.

Does the brain need carbohydrates to function?

The brain requires energy, but it does not require carbohydrates specifically. In the absence of dietary carbs, the liver supplies glucose through gluconeogenesis while ketones provide the majority of the brain’s energy needs. As ketone availability increases, the brain’s glucose requirement drops substantially without impairing function.

Is low-carb or ketogenic eating safe long term?

In metabolically healthy individuals, long-term low-carb or ketogenic diets are generally well tolerated and consistent with human physiology. The body is designed to operate across a range of fuel states, and safety depends more on overall nutrient adequacy, metabolic health, and individual context than carbohydrate intake alone.