Most people think they have a “slow metabolism” because weight loss feels hard, they get tired after meals, and they can’t go long without eating without turning into a hangry mess. But in a lot of cases, that isn’t a slow metabolism at all. It’s a metabolism that’s become overly dependent on constant incoming fuel—usually sugar and starch—to keep energy and mood stable.

And here’s the uncomfortable context: by strict criteria, only about 1 in 8 U.S. adults are considered metabolically healthy. In other words, 88 percent of people are already somewhere on the spectrum of metabolic dysfunction, whether they feel it yet or not. That’s why I’d argue metabolic flexibility is one of the most underestimated and neglected parts of metabolic health—and long-term health in general.

That’s what this article is about: metabolic flexibility. It’s your body’s ability to run smoothly in both modes—fed and fasted—and switch between them without crashes, cravings, brain fog, or that urgent “I need food now” feeling. When that switch works, you don’t just “feel better.” Blood sugar control becomes calmer. Hunger becomes less aggressive. Fat loss becomes less of a fight. Training feels less dependent on perfect meal timing. And your day stops being dictated by snacks, caffeine, and energy dips.

By the end of this article, you’ll understand exactly what metabolic flexibility is (in plain English), what’s supposed to happen in the fed and fasted state, and why modern life tends to break the switch. You’ll also be able to spot the most common signs of metabolic inflexibility in yourself, and you’ll leave with a practical plan to restore it—whether that means tightening meal timing, reducing carbs for a period, using nutritional ketosis as a shortcut, or simply adding the right kind of movement and recovery.

What is Metabolic Flexibility?

Before we define it, it’s worth clearing up one thing that confuses almost everyone: “metabolic flexibility” isn’t a single, locked-in clinical term with one universal definition. Researchers and clinicians use it slightly differently depending on context — exercise physiology tends to talk about fuel use during activity, while metabolic disease research tends to focus on how well someone shifts between burning fat and burning glucose in response to feeding, fasting, or insulin. Same underlying idea, different lens.

For our purpose — getting healthier in real life — we can define metabolic flexibility like this:

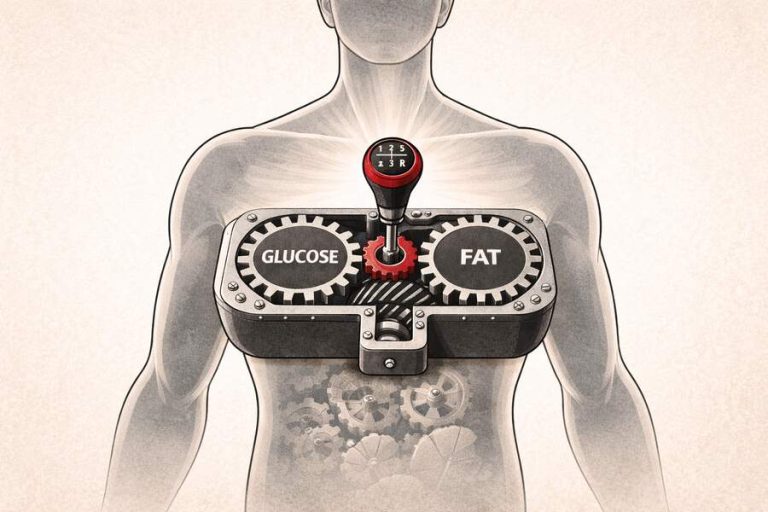

Metabolic flexibility is your body’s ability to match fuel use to the situation, smoothly and efficiently.

When you eat, you should be able to handle incoming energy without your blood sugar staying elevated for hours. When you haven’t eaten for a while, you should be able to access stored energy without crashing, getting shaky, or feeling like you urgently need food. When you move, your metabolism should be able to scale energy output without you feeling depleted or fatiguing too quickly.

A simple way to think about it is that a metabolically flexible body can run well in both modes — fed and fasted — and transition between them without drama. You’re not stuck relying on one fuel source. You’re not locked into constant grazing to feel normal. Your metabolism can “shift gears” without grinding. If this does not sound like something you’re capable of yet, then you’re likely one of the 88 percent of metabolically dysfunctional people.

People often reduce metabolic flexibility to “being good at burning fat,” but that’s only one aspect of it. The bigger picture is adaptability and stability. A flexible metabolism doesn’t fear glucose, and it doesn’t depend on glucose. It can use carbs when they’re available and useful, and it can lean on fat when they aren’t — all while keeping your energy, hunger, and mental clarity relatively steady.

That’s the key point: metabolic flexibility isn’t a diet identity. It’s a basic metabolic capability — and when it’s missing, a lot of modern health problems start making sense.

For an in-depth look at how the body processes and relies differently on glucose and fat, see this article here.

Fed vs Fasted Metabolism: The Two States You Must Handle

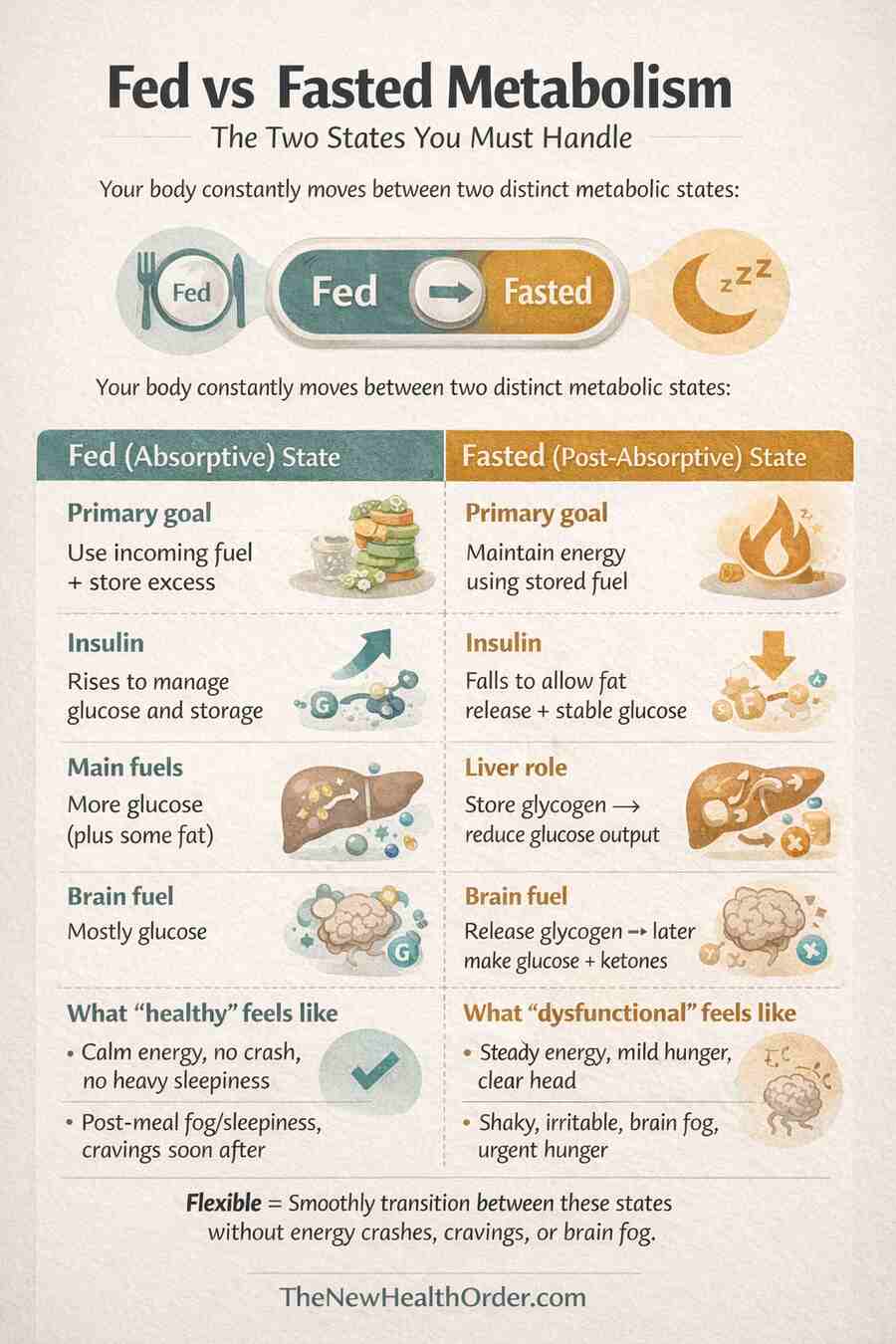

If metabolic flexibility is the ability to match fuel to the situation, then most of the time that situation falls into one of two broad states: fed or fasted. A metabolically healthy body moves between these constantly—sometimes multiple times a day—and the ease and quality of that transition has a big influence on your energy, hunger, mood, and long-term metabolic health.

If you regularly feel hangry, irritable, shaky, or suddenly desperate for food between meals, that’s often a sign your metabolism isn’t switching gears smoothly and is leaning too heavily on constant incoming fuel (glucose) to feel normal.

The Fed (Absorptive) State

The fed state is the period after you eat, when nutrients are actively arriving in your bloodstream. Glucose broken down from absorbed food rises, amino acids rise, and dietary fat begins to circulate as well. Your body’s job in this window is straightforward: use what you can, store what you don’t need immediately, and keep blood sugar in a safe range.

Insulin plays the role of traffic controller here. It helps move glucose into cells (especially muscle), supports glycogen storage in the liver and muscle, and nudges excess energy toward storage when there’s more coming in than you can burn. That’s not a flaw—it’s normal physiology. In a metabolically healthy person, the fed state is calm and quiet. Blood sugar rises modestly, comes back down predictably, and you feel steady rather than wired, sleepy, or ravenous soon after eating.

See this article here for a greater look into insulin’s role in the body and on health.

The Fasted (Post-Absorptive) State

The fasted state starts once the immediate flow of nutrients from a meal slows down—typically a few hours after eating—and it deepens overnight. In this state, your body’s job is to keep you fueled without relying on incoming food, which means shifting from “what’s coming in” to “what’s stored.”

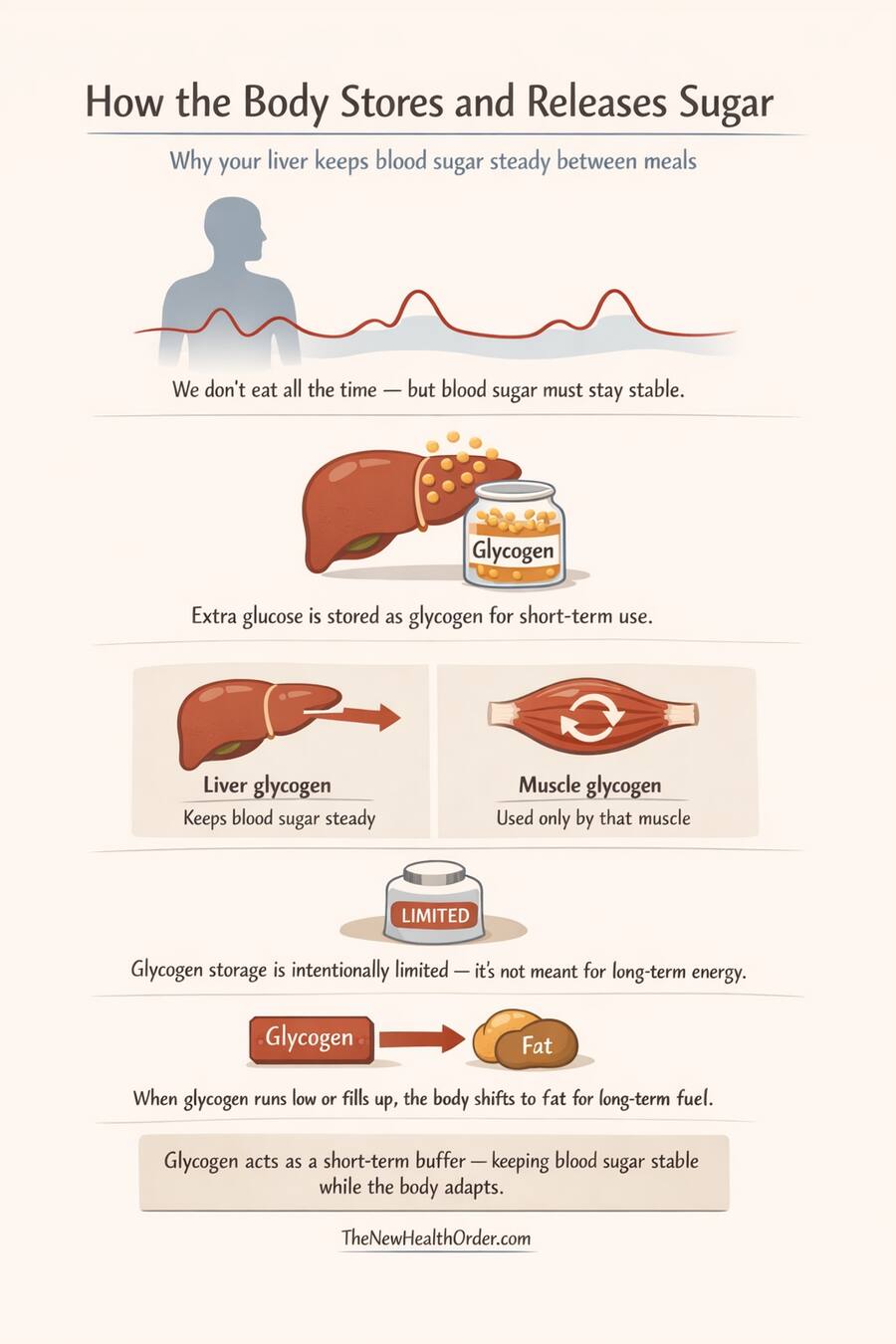

The first thing to know is what glycogen is. Glycogen is basically the body’s stored form of carbohydrate—think of it as glucose packed away for later, mainly in the liver (for keeping blood sugar stable) and in muscle (for local use during activity).

Early in the fasted state, your liver releases some of its glycogen to keep blood glucose steady for the tissues that still need it—especially red blood cells (which can only use glucose) and parts of the kidney.

At the same time, insulin is falling, which signals fat tissue to start releasing fatty acids. Most of the body—muscle, heart, and many organs—can use those fatty acids directly, so they begin leaning more on fat for energy fairly quickly. This doesn’t only happen once glycogen is gone; it ramps up alongside glycogen use as the “background fuel” between meals.

The brain is the exception. It can’t use fatty acids directly in any meaningful amount, so early on it still relies mostly on glucose. But if fasting continues long enough (or carbs remain very low), the liver converts some fatty acids into ketones—a clean, portable fuel that can cross into the brain. Ketones aren’t “magic” and they’re not just a waste product. They’re a normal backup fuel that helps your brain stay powered when glucose availability is lower.

For a deeper look at ketones and their importance for metabolic health, see this article here.

This is where metabolic flexibility becomes very real in day-to-day life. In a flexible metabolism, the transition into the fasted state feels relatively calm: energy stays steady, hunger rises gradually, and you can function normally without obsessing about food. If you can’t access stored energy efficiently yet, the fasted state feels like a problem. That’s when the classic signals show up—shakiness, irritability, brain fog, cravings, or a sudden dip in energy—because your body hasn’t learned to make that fuel handoff smooth.

What “Smooth Switching” Looks Like

A smooth switch doesn’t mean your body instantly flips a perfect on/off switch from glucose to fat. In real life there’s overlap. The key is that the transition is orderly and stable, not chaotic. As glucose becomes less available, fatty acid mobilization increases to offset the dip, thereby leaving no unfilled energy needs, and ensuring energy remains constant.

In a metabolically flexible system, several things happen consistently. In the first stage (roughly the first 4–12 hours after a meal), your liver helps keep blood glucose stable by releasing glucose from glycogen (stored carbohydrate), while many tissues—like muscle and the heart—begin increasing their use of fatty acids as insulin falls. Ketones may start to rise, but they’re usually still low at this point.

As fasting continues (roughly 12–24 hours, or sooner in someone who’s well-adapted), liver glycogen becomes more limited, fat-based fuel use becomes more dominant, and the liver produces more ketones from fatty acids. This is when ketones become meaningfully available as an alternative fuel—especially for the brain.

With longer fasting or sustained very low-carb intake (roughly 24–48 hours and beyond), the liver ramps up ketone production, and the brain begins using ketones for a large share of its energy. That shift matters because the brain’s glucose demand can fall dramatically: in a normal fed state, the brain runs on roughly 110–145 g of glucose per day, but after prolonged fasting, studies have shown this can drop to around ~40 g/day.

But it never drops to zero. Some tissues must run on glucose (red blood cells are the classic example), so your body keeps making a baseline supply via gluconeogenesis even when you’re deep into ketosis. In fact, the body is able to make between 180 – 220 g of glucose per day without any dietary glucose, enough to fuel the body fully.

For other changes in the body under fasting conditions, see this article here.

Practically, “smooth switching” looks like this: after meals you feel steady rather than foggy or sleepy, and between meals you don’t crash. Hunger rises gradually instead of spiking suddenly. You can go overnight without waking up ravenous, and you don’t feel like you need constant snacks or caffeine just to function. That’s the real fingerprint of metabolic flexibility: you can spend time in both states—fed and fasted—without your body acting like something has gone wrong.

Fed vs Fasted Metabolism

| Feature | Fed (Absorptive) State | Fasted (Post-Absorptive) State |

| Primary goal | Use incoming fuel + store excess | Maintain energy using stored fuel |

| Insulin | Rises to manage glucose and storage | Falls to allow fat release + stable glucose |

| Main fuels being used | More glucose (plus some fat) | More fatty acids; glucose buffered by liver |

| Liver role | Store glycogen; reduce glucose output | Release glycogen → later make glucose + ketones |

| Brain fuel | Mostly glucose | Glucose early; more ketones with longer fasting/very low carb |

| What “healthy” feels like | Calm energy, no crash, no heavy sleepiness | Steady energy, mild hunger, clear head |

| What “dysfunctional” feels like | Post-meal fog/sleepiness, cravings soon after | Shaky, irritable, brain fog, urgent hunger |

Why Metabolic Flexibility Matters for Health

A simple way to think about metabolic flexibility is that it’s the difference between a body that uses fuel, and a body that gets pushed around by it. When the switch is working, you can eat without crashing afterward, and you can go hours without eating without your energy or mood falling apart.

When it isn’t, the same patterns tend to show up everywhere—blood sugar feels unstable, hunger feels urgent, fat loss feels stubborn, and workouts feel overly dependent on perfect timing. The next four sections break down exactly how that plays out in real life.

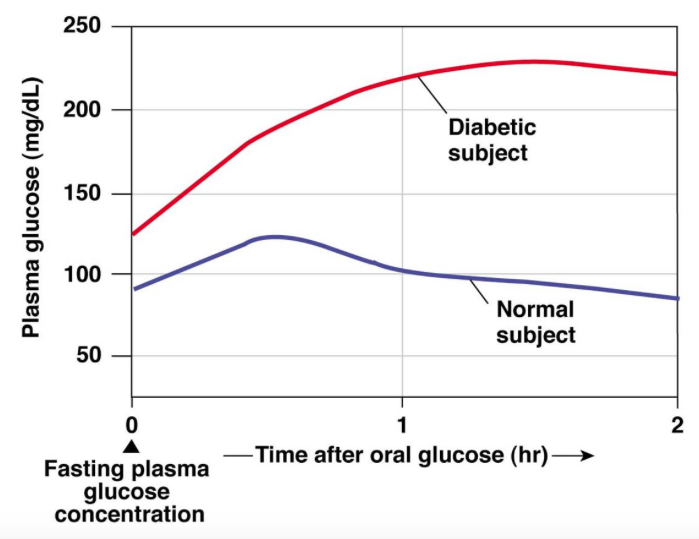

Blood Sugar and Insulin Sensitivity

Metabolic flexibility matters enormously for blood sugar regulation because it reflects whether your body can do what it’s designed to do after a meal: clear glucose efficiently, then switch back toward stored fuel once cleared.

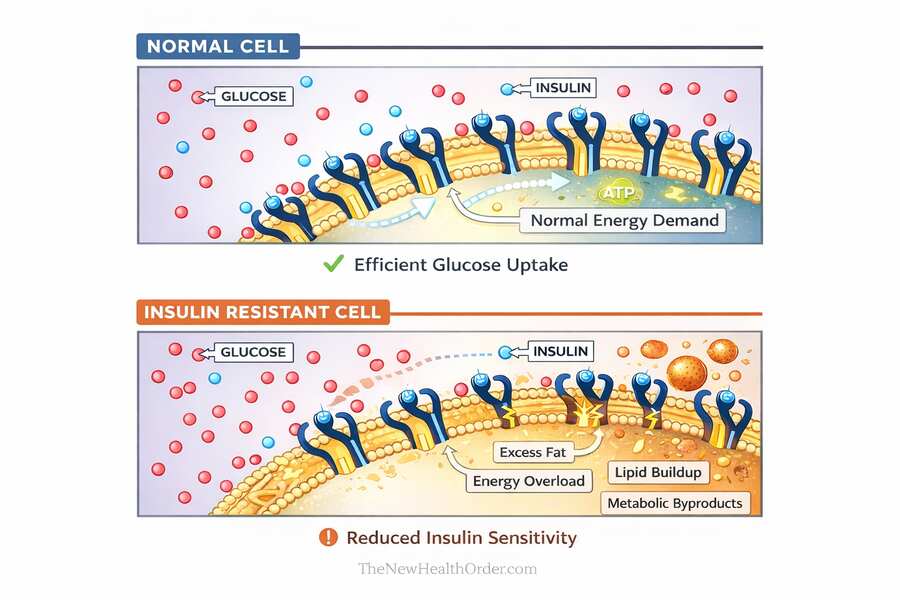

In the fed state, insulin rises to move glucose out of the bloodstream—mainly into skeletal muscle and the liver, where it can be used or stored as glycogen. When those tissues are insulin sensitive, glucose comes down in a predictable way and insulin doesn’t need to stay elevated for long. A few hours later, insulin falls and fat tissue releases fatty acids, so the body can run on stored energy without you feeling like you’re crashing.

When flexibility is poor, that coordination breaks down. Insulin resistance means muscle doesn’t take up glucose as well, the liver may keep producing glucose when it shouldn’t, and blood sugar stays higher for longer. The pancreas responds by pushing out more insulin, which can leave you stuck in a pattern of higher insulin, poorer fat access, and stronger hunger between meals.

That’s why this matters for health: chronically elevated glucose and insulin are key signals tied to insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, fat gain, and cardiometabolic risk. Metabolic flexibility is the healthy opposite: glucose is handled when it arrives, and your body can smoothly rely on stored fuel when it doesn’t.

Weight Regulation and Fat Loss

A lot of people blame a “fast” or “slow” metabolism for why weight loss feels easy for some and almost impossible for others. Sometimes there are real differences in energy expenditure, but often they are quick to identify themselves as victims of their metabolism – but not the cause of their metabolic inflexibility.

In a metabolically healthy rhythm, insulin rises after you eat to handle incoming fuel, then it falls again as you move into the post-absorptive state. When insulin is low enough, fat cells can release fatty acids, and your muscles and other tissues can burn them for energy. That’s the basic “stored fuel” system working as intended.

When metabolic flexibility is poor, people often spend most of the day in a semi-fed state—frequent eating, higher baseline insulin, and a weaker shift into fat use between meals.

The result is that fat stores become harder to tap, not because fat is magically locked, but because the hormonal and metabolic signals that allow fat mobilization aren’t happening consistently. That’s when appetite tends to feel louder, energy dips hit harder, and adherence becomes the real bottleneck.

This is also why weight loss tends to improve so many health markers—even when the diet isn’t clean. Dropping excess fat (especially visceral fat around the organs and fat stored in the liver) often improves insulin sensitivity, triglycerides, blood pressure, and fatty liver risk simply because the body is under less metabolic strain. That’s the real lesson behind the “I ate junk food and my labs improved” stories: the improvement usually came from being in a calorie deficit and losing weight, not from the food quality itself.

So metabolic flexibility doesn’t guarantee weight loss, but it makes weight regulation far less of a fight: you can go longer between meals without crashing, you’re less driven by urgent hunger, and your body is more willing to run on its own stored energy.

Energy Levels, Mood, and Cognitive Stability

One of the most practical reasons metabolic flexibility matters is that it shows up in how you feel day to day. A metabolically flexible body can keep energy output relatively steady as you move through the day, instead of relying on frequent hits of food—especially carbs—to feel normal.

When metabolically flexible, you are not reliant on periodic meals and can go long stretches without eating while energy stays surprisingly stable. I can go 48 hours without a meal without feeling much energy disturbance at all, and I believe most healthy bodies should be able to do the same, assuming they have sufficient fat stores to begin with and are not malnourished or underweight.

Hunger still shows up, but it’s usually very mild, periodic, and in no way affects your mood or focus. It’s more of a gentle reminder that you haven’t eaten in a while instead of a full-blown hostage negotiation led by your stomach. That’s a pretty good real-world sign that your body can cover the gap with stored fuel rather than sounding the alarm the moment incoming fuel stops.

When flexibility is poor, you get an energy lag between fuels. As glucose availability drops, the body should ramp up fat use (and, over longer fasts or very low carb intake, ketones). If that ramp-up is sluggish, the brain and nervous system feel it first: brain fog, irritability, shaky urgency, cravings, and that restless “I need to eat now” feeling. Those are signals that the body has not smoothly transitioned between fuel sources.

On the flip side, the fed state can also reveal a lot. If you regularly feel sleepy, foggy, or like you need a nap after eating, that can be a sign you’re not handling the meal smoothly—often because blood sugar rises higher than it needs to, stays elevated too long, or swings (up then down) in a way that leaves you drained. Large or very high-carb meals may do this regardless, but becoming tired or sleepy after an average meal is not the norm.

Exercise Capacity and Recovery

Metabolic flexibility matters for exercise because training is basically a controlled energy crisis. The moment you start moving, your muscles need more fuel—fast—and the “best” fuel depends on what you’re doing. Higher intensity work leans more on glucose (and muscle glycogen), while lower intensity and longer duration work relies more on fat oxidation. A flexible metabolism can shift along that spectrum without you feeling like you hit a wall the moment conditions change.

When flexibility is poor, exercise often feels harder than it should. You fatigue early and get that shaky feeling if you haven’t eaten recently. This was one of the most noticeable effects of being metabolically inflexible when I first started to transition – it took me a good few weeks to be able manage my energy when exercising after reducing carbohydrate intake. Now, however, I can exercise when fasted with little detriment.

Recovery is just as noticeable as the exercise itself. After training, you want to replenish glycogen, repair tissue, and calm inflammation. Insulin sensitivity in muscle typically improves after exercise, which helps shuttle nutrients where they need to go. A metabolically flexible system tends to bounce back faster: steadier appetite, better energy the next day, and less food and energy cravings following hard sessions.

The practical takeaway is that metabolic flexibility isn’t just about food and diet—it’s about performance and resilience. The more options your body has for fueling work and restoring itself afterward, the less fragile you feel when meals, training times, or life schedules aren’t perfectly controlled.

Signs You’re Flexible vs Inflexible

Metabolic flexibility isn’t something you need a lab test to notice. In real life, it shows up as how stable you feel between meals, how you respond to food, and how your energy behaves when conditions change.

Signs of Good Flexibility

- You can go 4–6+ hours between meals without crashing or getting shaky

- Hunger is mild and gradual, not urgent or aggressive

- You feel steady after meals (no heavy sleepiness, fog, or sudden slump)

- You can exercise without perfectly timing food, especially at lower intensities

- If you miss a meal, you feel mostly normal (just “I could eat,” not “I need to eat now”)

- Your mood and focus stay relatively stable across the day

- After an indulgent meal/day, you return to baseline quickly (less “hangover” effect)

- Your one-off strength output doesn’t fall apart just because you haven’t had carbs (though repeated all-out sets may drop)

- An occasional 24-hour fast feels manageable and doesn’t cause a dramatic energy crash

- Even longer gaps (up to 36–48 hours, in someone with adequate fat stores) feel mostly steady rather than like an emergency

Signs of Metabolic Inflexibility

- You get hangry, irritable, anxious, or foggy when meals are delayed

- Energy drops sharply a few hours after eating; you feel like you need frequent snacks

- Strong cravings (especially for quick carbs) appear when you’re hungry

- You feel sleepy or sluggish after meals more often than you’d expect

- Exercise feels worse when fasted; you get shaky or feel fatigued easily

- Hunger feels urgent and distracting, not mild and periodic

- Your energy and mood feel tightly tied to constant food intake or caffeine

- Longer gaps without food (around 24 hours or more) feel dramatic—energy, mood, and focus drop sharply

- Your strength output noticeably drops if you haven’t eaten recently, and training feels dependent on carbs or perfect meal timing

Signs of Flexibility vs Inflexibility

| In daily life… | More flexible looks like | More inflexible looks like |

| Between meals | Stable energy, hunger is mild | Crashes, shakiness, hangry urgency |

| Appetite | “I could eat” | “I need to eat now” |

| After meals | Steady, clear | Sleepy/foggy, cravings rebound |

| Fasting tolerance | 12–24h manageable; longer possible if not underweight | 24h feels dramatic; mood/energy drops hard |

| Training | Less dependent on meal timing | Performance feels fragile without carbs/food |

| Cravings | Occasional, manageable | Loud, urgent, often carb-specific |

Why Metabolic Inflexibility Develops in Modern Life

If you recognized yourself in the “inflexible” list, the next question is obvious: why does this happen to so many people now? For most, it isn’t bad genetics or a lack of discipline. It’s that modern life quietly removes the very conditions your metabolism evolved to handle.

Constant Feeding + Low Movement

For most of human history, eating wasn’t constant. There were natural gaps—hours, often days—where the body had to rely on stored fuel. And daily life involved a lot more movement, often at low-to-moderate intensity. That combination matters because it creates a normal rhythm: periods of incoming energy, followed by periods where the body has to switch to stored energy. That rhythm is basically “practice” for metabolic flexibility.

Modern life flips that. Many people spend most of the day in a semi-fed state: breakfast, snacks, coffees, lunch, something in the afternoon, dinner, dessert—often with very little time spent truly post-absorptive. Even if the portions aren’t huge, the constant drip-feed keeps insulin elevated more often than it should be, and it reduces the number of opportunities your body has to fully shift into fat-based fuel use.

At the same time, energy demand is often low. When movement is mostly optional and much of the day is spent sitting, the body simply doesn’t have to burn through much fuel. And if energy demand is low while energy supply is frequent, you end up with the perfect setup for metabolic inflexibility: the body is constantly processing incoming energy, but rarely forced to get good at accessing stored energy.

The Mitochondrial “Supply Exceeds Demand” Problem

Here’s the deeper mechanism that ties it all together. Metabolic inflexibility isn’t just about hormones or willpower—it’s about what’s happening at the level of the mitochondria, the “engines” inside your cells.

In a healthy system, fuel supply roughly matches fuel demand. After a meal, mitochondria burn more glucose. Between meals, they burn more fatty acids. During activity, demand rises and mitochondria pull in and use more fuel cleanly.

But when fuel is always coming in and demand stays low, mitochondria are stuck in a chronically over-supplied state—more fuel arriving than is actually needed. Think of it like revving an engine while the car is barely moving. Over time, this “energy congestion” creates metabolic spillover: incomplete fuel processing, oxidative stress signals, and fat being stored in places it doesn’t belong (like liver and muscle). Those changes are closely tied to insulin resistance, and once insulin resistance sets in, switching fuels becomes even harder—because the body gets worse at handling glucose after meals and worse at shifting to fat between meals.

This is the core pattern: constant supply + low demand → mitochondrial overload → insulin resistance → reduced fuel switching. Once you see that loop, the solution becomes much more obvious—and it’s not complicated. You restore flexibility by reintroducing the conditions that reduce congestion and rebuild the switch: periods without constant intake, and enough movement to raise real energy demand.

How Metabolic Flexibility Is Restored in Practice

Restore the Fed–Fasted Rhythm

This part is about frequency. The goal is to stop living in a constant “semi-fed” state where insulin never really comes down and the body never has to practice running on stored fuel. For many people that simply means distinct meals, fewer snacks, and a consistent overnight fasting window. It may sound like a “hack”, but all you’re doing is just giving your metabolism enough uninterrupted time to shift into the post-absorptive state and do normal fat-based fueling between meals.

If you’re relatively healthy, that alone can make a noticeable difference: steadier appetite, fewer crashes, and less obsession with food. But if you’re strongly metabolically inflexible, this lever can feel uncomfortable at first—because the switch is rusty. That’s where the next lever matters.

Improve Fuel Balance and Lower Glucose Pressure

This part is about intake. If most of your meals are carb-heavy and you’re already insulin resistant, spacing meals out can feel like extending the crash rather than fixing it. In that case, reducing carbohydrate intake—at least temporarily—can make the switch dramatically easier because insulin stays lower for longer and fat release becomes more available.

For many people, reaching nutritional ketosis is the fastest way to do this. It’s not the only route, but it’s often the most direct: carbs are low enough that the body is forced to practice using fatty acids and ketones, hunger tends to quiet down, and energy becomes steadier between meals.

Once that stability is restored, some people can reintroduce carbohydrates strategically without immediately returning to the crash-and-crave cycle—because their metabolism is no longer dependent on constant glucose.

See this article here for a deeper look at the effect of carbohydrates on the body and metabolic health.

Increase Energy Demand (Movement/Exercise)

If restoring flexibility is about switching fuels smoothly, movement is what trains that ability—because it raises energy demand and forces your body to actually use the fuel you’re storing.

The key point is that exercise doesn’t just “burn calories.” It makes your muscles more willing to take up and use glucose, it increases mitochondrial capacity over time, and it trains your body to handle both fuels depending on intensity.

Low-intensity movement (like walking) pushes fat oxidation and improves baseline fuel use. Higher intensity work and resistance training improve glucose handling, glycogen storage, and insulin sensitivity in muscle—basically increasing the size and efficiency of your main glucose sink.

You don’t need perfection here. Consistency matters more than the ideal program. A daily baseline of walking plus a few sessions a week of resistance training (and optionally some intervals) is enough to shift most people’s metabolism in the right direction—especially when combined with cleaner meal timing and lower glucose pressure.

One important point, though: movement can raise demand, but it can’t always compensate for a constant, high-glucose intake—most people simply can’t out-train continuous food overload. The best results come from using both levers together: enough movement to pull fuel through the system, and enough dietary control to stop reloading the congestion all day long.

Improve Recovery and Food Quality

This is the part that makes flexibility sustainable instead of fragile.

If sleep is poor and stress is high, your body runs more “reactive”: appetite goes up, cravings get louder, glucose control worsens, and fasting feels harder than it should. Recovery directly affects the hormones and nervous system signals that determine whether you feel stable between meals. Solid sleep, sensible training volume, hydration, and stress management make fuel switching smoother and reduce the sense of urgency that drives snacking.

Food quality matters for a different reason: ultra-processed food makes it extremely easy to overshoot energy intake without noticing and keeps the brain’s reward system pulling you back for more.

A whole-food base—adequate protein, minimally processed carbs (if you include them), and better fat sources—makes appetite more predictable and meal spacing easier. It also improves micronutrient intake and reduces the “mixed-fuel overload” problem that tends to happen when highly palatable carbs and fats are combined all day long.

Importantly, none of this requires banning entire food groups forever. The goal is to rebuild a metabolism that can handle food when it arrives and remain calm when it doesn’t—without crashes, cravings, or constant negotiation.

Final Thoughts

Metabolic flexibility is really just fuel stability. When it’s working, you can handle a meal without a crash, and you can go hours without eating without your mood, focus, and energy falling apart. You’re not running on emergency signals all day, and fat loss and training stop feeling like they require perfect timing.

The clearest signs you’re lacking flexibility are also the most common: getting hangry or shaky when meals are delayed, brain fog when hungry, urgent cravings, frequent post-meal fatigue, and a feeling that you need snacks or caffeine just to stay level. In more obvious cases, even longer gaps without food feel dramatic, and strength or workout performance feels fragile unless you’ve eaten recently.

The good news is that these symptoms usually improve in a predictable way once the fuel switch starts coming back online. Hunger becomes quieter and more gradual. Energy between meals steadies out. Post-meal sleepiness and cravings fade. Training feels less dependent on perfect meal timing, and recovery becomes smoother.

To improve metabolic flexibility, focus on three levers. First, restore a real fed–fasted rhythm by cutting grazing and creating clean gaps between meals so insulin can come down and your body can practice using stored fuel. Second, if you’re carb-dependent or insulin resistant, lower glucose pressure—often by temporarily reducing carbs, and for many people the fastest route is a period of nutritional ketosis. Third, increase energy demand with consistent movement and strength training, then make it sustainable with good sleep, stress management, and mostly whole foods.

The goal isn’t to live in one extreme. It’s to build a metabolism that isn’t fragile—one that can use glucose when it’s available, and can run calmly on stored fuel when it isn’t.

FAQs

What is metabolic flexibility?

Metabolic flexibility is your body’s ability to use the right fuel at the right time—and switch smoothly without drama. After you eat, a flexible metabolism can clear glucose efficiently (blood sugar rises modestly, then comes back down) and store what you don’t need. Between meals, it can access stored fuel (mainly fatty acids, and later ketones if carbs are low) so your energy and mood stay steady.

How do I know if I’m metabolically inflexible?

If you get hangry, shaky, foggy, or anxious when meals are delayed, need frequent snacks or caffeine to feel “normal,” or crash after eating, that’s a classic sign. Exercise may feel unusually hard when fasted, and longer gaps without food (24+ hours) can feel dramatic rather than manageable. These patterns usually mean your body struggles to transition from incoming glucose to stored fuel smoothly.

What’s the fastest way to improve metabolic flexibility?

Combine three levers: stop grazing (create clean gaps between meals), increase daily movement (walking + resistance training), and—if you’re carb-dependent or insulin resistant—temporarily lower carbs to reduce glucose pressure and make fat/ketone use easier. Most people notice hunger quieting, steadier energy between meals, fewer cravings, and less need for perfect meal timing within weeks.