Insulin is one of the most talked-about hormones in modern health—and one of the most poorly explained. It’s commonly associated with weight gain, fat storage, and metabolic disease, and often discussed as something that needs to be tightly controlled or kept low.

For many people, this idea feels reasonable. Lowering insulin through dietary changes can improve blood sugar control, reduce hunger, and lead to weight loss. But insulin didn’t become a problem on its own, and understanding why it’s so closely tied to metabolic dysfunction matters more than simply trying to suppress it.

This article is not about dismissing insulin or questioning the usefulness of low-carbohydrate diets. It’s about explaining what insulin actually does in the body, how insulin resistance develops, and why modern conditions place constant strain on a system that normally works very well.

By the end, you’ll have a clearer understanding of the difference between insulin and insulin resistance, why certain approaches provide relief, and why long-term metabolic health depends less on avoiding insulin and more on restoring balance and normal responsiveness.

If you’ve ever felt unsure how insulin fits into the bigger picture of health, this article will give you a framework that makes the rest of the conversation easier to understand.

What Is Insulin?

Insulin is a hormone produced by the pancreas in response to incoming nutrients. Despite how it’s usually talked about, its primary role isn’t weight gain or fat storage. It’s something far less dramatic, but far more important: metabolic safety. Insulin exists to keep energy moving through the body in a controlled, non-damaging way.

One of insulin’s most important—and least discussed—functions is protecting cells from excess glucose. Glucose is a useful fuel, but it is also chemically reactive, and can become toxic when left to accumulate. When glucose remains in the bloodstream for too long, it begins to bind to proteins and cellular structures in a process known as glycation.

Over time, this damages tissues, disrupts normal function, and contributes to many of the complications associated with metabolic disease. Insulin prevents this by clearing glucose from the blood before it becomes harmful.

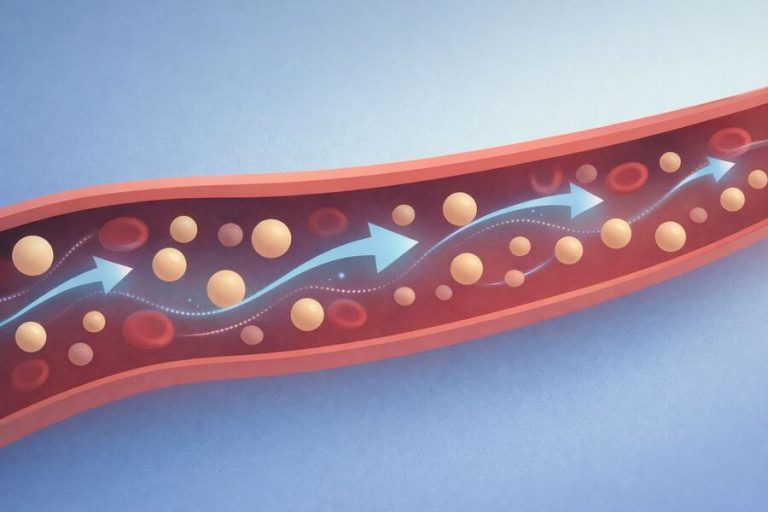

This makes insulin less of a storage hormone and more of a traffic controller. When energy enters the system, insulin signals that fuel is available and helps direct it where it can be safely used or temporarily stored. How that fuel is handled depends on the tissue involved.

Muscle cells respond to insulin by absorbing glucose for immediate energy or future activity. The liver uses insulin to regulate how much glucose is released into the bloodstream or stored for later use. Other tissues rely on insulin signaling to maintain steady access to fuel between meals.

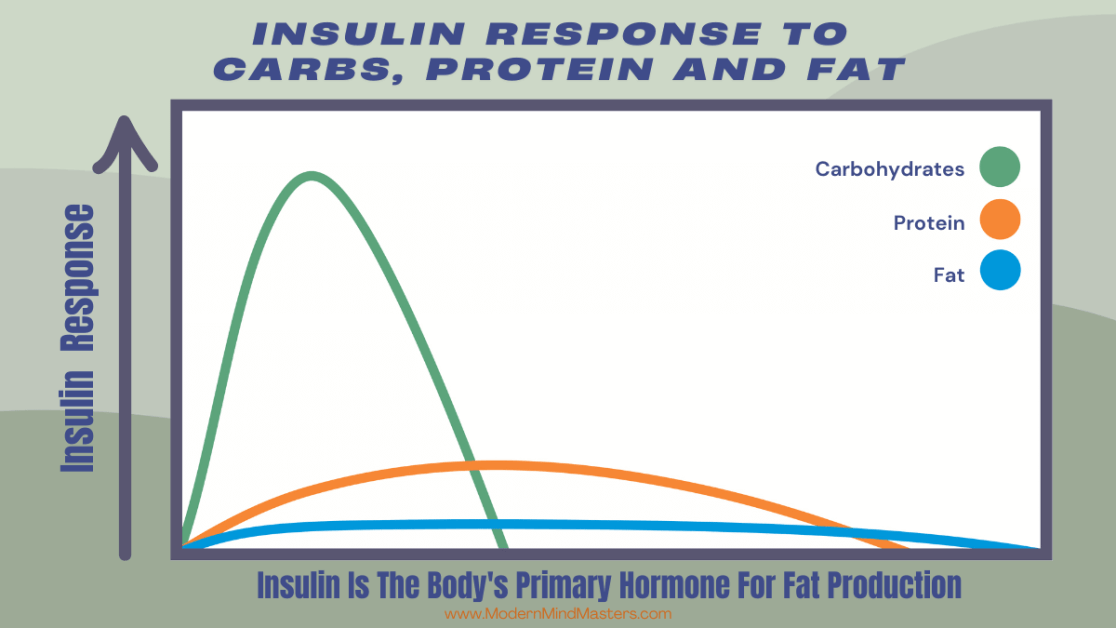

Contrary to popular belief, insulin is also not triggered by carbohydrates alone. While fat has a very small insulin response, protein intake stimulates insulin because it is required for amino acids to enter cells and support repair, maintenance, and growth. Without insulin, muscle tissue would break down faster than it could be rebuilt. This anabolic, protective role is essential for survival and recovery.

In a healthy body, insulin is dynamic. It rises when nutrients enter the bloodstream, completes its regulatory work, and then falls back to low levels. This rise-and-fall pattern is normal and necessary. Problems do not arise because insulin exists, but because the body is placed in conditions where insulin signaling is required constantly, without relief.

Understanding insulin as a protective, regulatory hormone—rather than a fat-storage switch—changes how we interpret both health and disease. It shifts the question away from how much insulin is present, and toward why the body is being asked to produce it so often.

Why Insulin Became the Villain

Insulin often gets a bad rap as the hormone that causes fat gain and blocks fat burning. In modern nutrition discussions, it is frequently treated as something to minimize or avoid altogether. This view did not arise randomly, nor is it entirely disconnected from real experience.

Many people improve their health by lowering carbohydrate intake or reducing how often they eat. These approaches reduce insulin levels, and the improvements that follow—weight loss, better blood sugar control, reduced hunger—can feel decisive. When lowering insulin produces results, it is easy to assume that insulin itself was the problem.

Over time, this assumption hardened into a narrative. Because insulin resistance is closely associated with obesity and metabolic disease, insulin became blamed for the condition rather than examined as part of the body’s response to metabolic stress. Elevated insulin came to be seen as the cause of dysfunction instead of a signal that regulation had already begun to fail.

This framing also reflects a broader frustration with decades of dietary advice that emphasized frequent eating and high carbohydrate intake. When insulin entered the conversation, it provided a simple explanation for why those approaches often failed. Insulin became a stand-in for a deeper metabolic mismatch.

For a deeper dive into how carbohydrates affect insulin response, see this article here.

The problem with this story is not that insulin matters—it does—but that it assigns blame to a hormone that plays a central role in normal energy regulation. Insulin did not suddenly become harmful. The environment it operates in changed, and the narrative shifted with it.

Insulin’s Roles in the Body

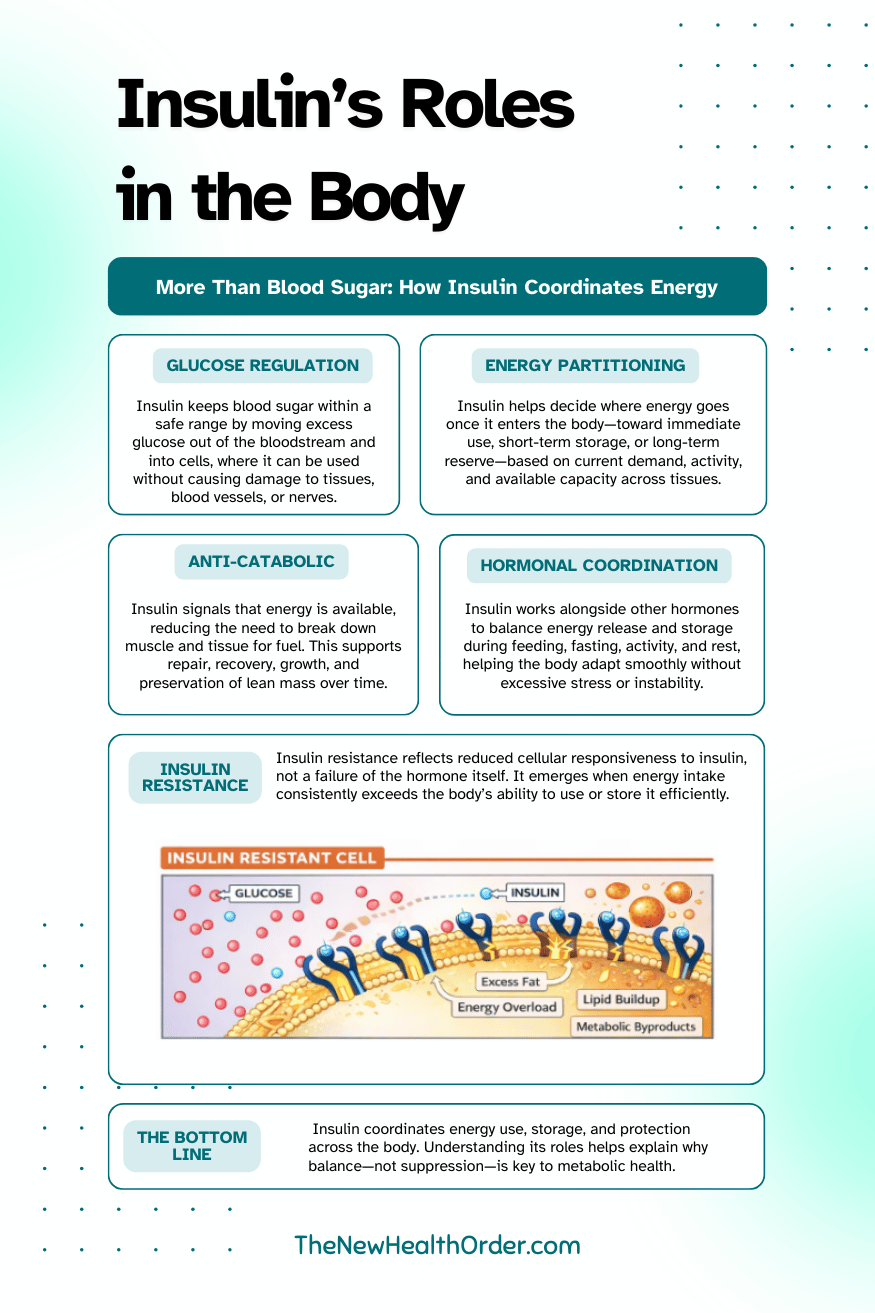

Once insulin is stripped of its reputation, its actual role becomes much easier to understand. Insulin is not a command to store fat. It is a coordinator, quietly managing what happens to energy once it enters the system.

Blood Glucose Regulation

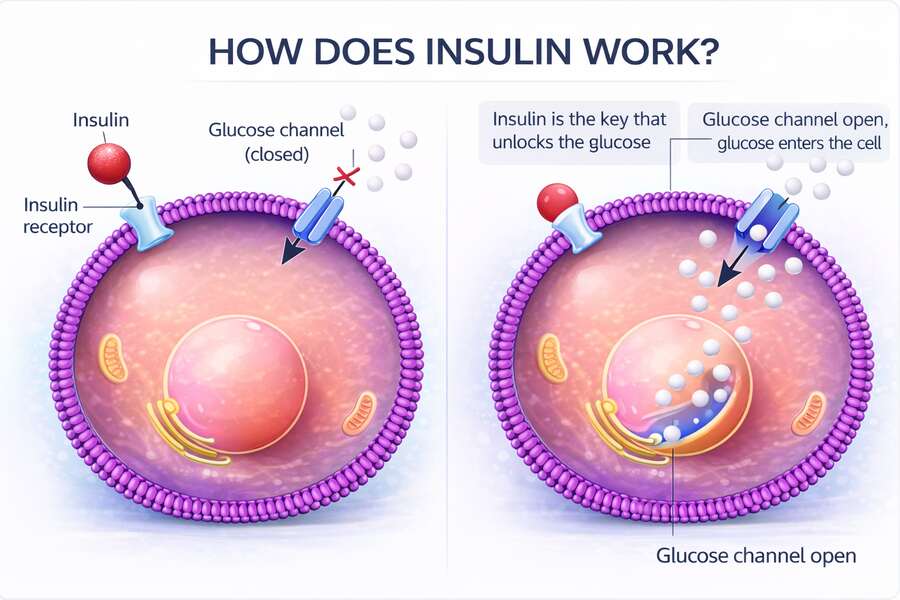

One of insulin’s most important jobs is regulating blood glucose. Glucose is a useful and efficient fuel, but it is not something the body can leave circulating freely for long periods. When glucose remains in the bloodstream too long, it begins to interfere with normal cellular function and damage tissues over time.

Insulin prevents this by clearing excess glucose from the blood and directing it into cells where it can be used safely. This protects organs, blood vessels, and nerves from unnecessary exposure to high glucose levels. In this sense, insulin acts less like a storage signal and more like a safety mechanism.

Without insulin, blood sugar would rise uncontrollably, cells would struggle to access energy, and long-term damage would accumulate. Regulating blood glucose is not a secondary function of insulin—it is the foundation of its role in human physiology.

Energy Partitioning

Insulin also helps determine where energy goes once it enters the body. When nutrients are absorbed, insulin coordinates whether that energy is used immediately, stored for short-term needs, or reserved for later.

Muscle tissue responds to insulin by taking in glucose to support movement, repair, and growth. The liver responds by regulating how much glucose is released into the bloodstream or stored as glycogen. Other tissues rely on insulin signaling to maintain a steady supply of fuel between meals.

Fat storage is part of this process, but it is not insulin’s primary objective. Storing energy as fat occurs when immediate needs are met and storage elsewhere is limited. Insulin allows this to happen when appropriate; it does not force it by default.

See this article here for an in-depth look at how glucose and fat differ in terms of energy production and metabolic health.

Where Insulin Directs Energy in the Body

| Tissue / Destination | What Insulin Does | Primary Purpose |

| Muscle | Signals muscle cells to absorb glucose and amino acids | Immediate energy, repair, and growth |

| Liver | Regulates whether glucose is released into the blood or stored as glycogen | Blood sugar stability and short-term energy storage |

| Brain & Organs | Helps maintain stable access to circulating energy | Continuous function and protection |

| Adipose (Fat Tissue) | Allows excess energy to be stored once other needs are met | Long-term energy reserve |

Anti-Catabolic Protection

Another underappreciated role of insulin is protecting muscle and tissue from unnecessary breakdown. In low-insulin states, the body increases reliance on stress hormones to release energy, which can accelerate the breakdown of muscle protein.

Insulin helps counter this by signaling that energy is available, reducing the need to dismantle existing tissue. This is why insulin rises after protein intake as well as carbohydrates. Repair, maintenance, and recovery all depend on insulin’s ability to limit excessive catabolism.

This protective function is especially important during periods of growth, physical training, injury recovery, and normal daily wear and tear. Without insulin’s moderating influence, maintaining lean tissue would be far more difficult.

Hormonal Coordination

Insulin does not act alone. It operates as part of a broader hormonal network that includes glucagon, cortisol, growth hormone, and others. Together, these hormones regulate how energy is released, stored, and conserved under different conditions.

When insulin is present, it signals that energy is available and that stress-driven energy release can be reduced. When insulin falls, counter-regulatory hormones rise to ensure fuel remains accessible. This balance allows the body to adapt to feeding, fasting, activity, and rest without extreme swings.

Problems arise when this coordination is lost and insulin signaling is required continuously. At that point, the system becomes strained, and the body begins to resist the signal itself. Understanding this balance is key to understanding why insulin resistance develops—not because insulin is harmful, but because regulation has been overused.

Insulin vs. Insulin Resistance

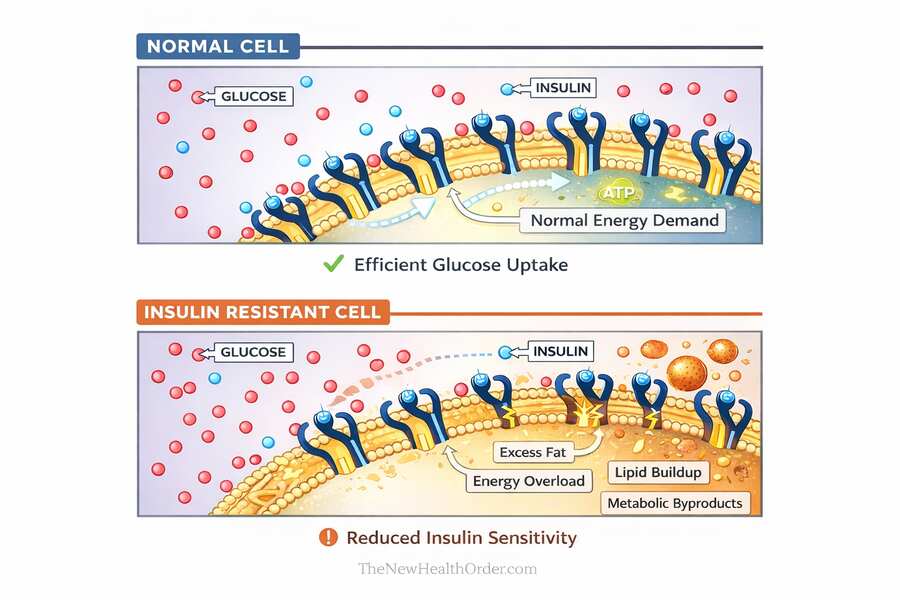

Insulin and insulin resistance are often discussed together, which can blur an important distinction. Insulin is a hormone the body relies on to manage energy. Insulin resistance refers to a reduced cellular response to that hormone, not to insulin itself.

In a healthy system, insulin rises when nutrients enter the bloodstream and cells respond by absorbing and using that energy. Once the job is done, insulin levels fall. This rise-and-fall pattern allows the body to move smoothly between fed and fasted states.

Insulin resistance develops when cells are repeatedly exposed to more energy than they can comfortably manage. Over time, they become less responsive to insulin as a protective adaptation. When this happens, the body compensates by producing more insulin in an attempt to keep blood glucose under control.

This is where confusion often arises. Elevated insulin is usually a response to insulin resistance, not the original cause. By the time insulin levels are consistently high, the system is already under strain.

Understanding this distinction matters. If insulin itself were the problem, suppressing it indefinitely would make sense. But if insulin resistance is the issue, the goal becomes restoring normal responsiveness rather than avoiding insulin altogether.

Why Insulin Resistance Develops

Insulin resistance does not develop overnight, and it is rarely caused by a single food or a single habit. It emerges gradually when the body is asked to manage more energy than it can comfortably process, day after day, without enough opportunity to reset and recover.

At a cellular level, insulin resistance is best understood as a protective response. When cells are repeatedly exposed to excess energy, they begin to limit how much more they are willing to accept. Becoming less responsive to insulin reduces the rate at which fuel enters the cell, helping prevent overload and damage.

Several factors contribute to this process. Chronic overconsumption of calories, especially in the absence of sufficient physical activity, increases the demand placed on insulin signaling. Over time, the system is required to stay “on” almost constantly. This sustained signaling is very different from the intermittent rises and falls insulin was designed for.

Low physical demand plays an important role. Muscle tissue is one of the body’s largest energy sinks. When muscle activity is low, less incoming energy is used, and more must be stored or managed elsewhere. This increases metabolic pressure and accelerates the loss of insulin sensitivity.

Inflammation, poor sleep, and chronic stress further compound the problem. These factors interfere with normal signaling and raise the baseline demand for insulin, even when food intake has not changed dramatically. The result is a system that relies more and more on insulin to maintain stability.

Common Contributors to Insulin Resistance

| Contributing Factor | How It Affects Insulin Signaling |

| Chronic Energy Surplus | Repeated excess energy intake increases the demand placed on insulin, forcing the signal to remain elevated for long periods without relief. |

| Low Physical Activity | Reduced muscle use limits one of the body’s main energy sinks, leaving more incoming fuel to be stored or managed elsewhere. |

| Constant Eating | Frequent meals and snacks reduce opportunities for insulin levels to fall, preventing normal recovery between feeding periods. |

| Inflammation | Chronic inflammation interferes with normal cellular signaling, making cells less responsive to insulin over time. |

| Poor Sleep | Sleep disruption alters hormonal balance and increases baseline insulin demand, even when diet remains unchanged. |

| Chronic Stress | Ongoing stress raises counter-regulatory hormones that increase glucose release and insulin requirements. |

| Reduced Metabolic Recovery | Lack of fasting periods, rest, or variation in energy demand prevents the system from resetting and restoring sensitivity. |

Insulin resistance, then, is not a failure of insulin itself. It reflects a mismatch between energy intake, energy use, and recovery. When that mismatch persists, normal regulation becomes strained, and responsiveness declines.

This explains why approaches that reduce insulin demand—such as eating less frequently or lowering carbohydrate intake—often provide relief. They reduce pressure on the system. But lasting improvement requires addressing the conditions that caused insulin signaling to be overused in the first place.

Why Low-Carb Diets Often Work

In recent years, low-carbohydrate and ketogenic diets have been widely discussed as ways to address insulin resistance and metabolic dysfunction. Their popularity isn’t accidental, and it isn’t based on theory alone.

Low-carbohydrate diets tend to work because they reduce the amount of insulin the body needs to produce on a daily basis. For someone who is insulin resistant or metabolically stressed, this reduction can provide immediate relief, and is often the most meaningful first-step a person can take in reversing insulin resistance.

By limiting carbohydrate intake, blood glucose rises less often and insulin is required less frequently. This gives cells a break from constant signaling and allows the system to operate in a lower-pressure state. For many people, this leads to improved blood sugar control, easier access to stored energy, and reduced hunger.

Lower insulin levels also make it easier to shift toward using fat for fuel. When insulin demand drops, the body relies less on glucose and more on stored energy between meals. This often results in weight loss, especially in the early stages, without the constant hunger that accompanies many calorie-restricted diets.

These benefits are real, which is why low-carb approaches have helped so many people when other strategies failed. The mistake is not in recognizing their effectiveness, but in assuming that their success means insulin itself is harmful.

Low-carb diets work by reducing metabolic pressure, not by eliminating a dangerous hormone. They simplify the energy environment and allow disrupted signaling to recover. This is particularly useful during periods of metabolic repair.

However, lowering insulin demand is a strategy, not a definition of health. The long-term goal is not to suppress insulin indefinitely, but to restore the body’s ability to respond to it appropriately. When insulin sensitivity improves, the system becomes more flexible, and energy can be handled without constant restriction.

For more information about ketogenic diets and their role in overcoming insulin resistance, see this article here.

Insulin and Diabetes

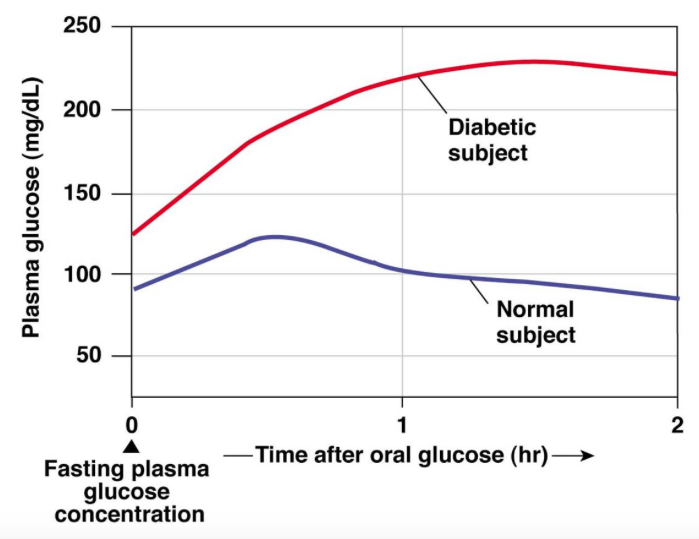

Because insulin is so closely associated with diabetes, it’s often discussed as if the two are inseparable. This connection is understandable, but it can also be misleading if the relationship isn’t explained carefully.

In simple terms, diabetes reflects a breakdown in insulin regulation—not insulin itself. In type 1 diabetes, the body no longer produces sufficient insulin, making external insulin essential for survival. In type 2 diabetes, insulin is still produced, often in large amounts, but cells no longer respond to it properly. The problem is not the presence of insulin, but impaired signaling.

In both cases, insulin plays a central role in managing blood glucose. Without effective insulin action, glucose remains in the bloodstream longer than it should, increasing the risk of tissue damage over time. This is why insulin therapy, when required, is lifesaving rather than harmful.

It’s also important to recognize that diabetes develops gradually. Long before blood sugar rises into the diabetic range, insulin signaling is often under strain. The body compensates by producing more insulin to maintain normal glucose levels. By the time diabetes is diagnosed, this compensatory system has usually been overwhelmed.

Understanding this progression helps clarify insulin’s role. Insulin is not the cause of diabetes, but a hormone the body relies on increasingly as regulation begins to fail. Treating insulin as the enemy obscures the real issue, which is the loss of normal responsiveness over time.

This distinction matters because it reframes both prevention and recovery. The goal is not to eliminate insulin, but to reduce the conditions that force the body to depend on it excessively. Restoring healthier signaling, rather than suppressing insulin outright, is what ultimately protects metabolic health.

The Real Problem: Chronic Metabolic Mismatch

When insulin is viewed in context, a clear pattern emerges. Insulin itself is not the problem. The issue lies in the conditions under which it is asked to operate.

Human metabolism evolved to handle periods of feeding and fasting, activity and rest. Energy intake was intermittent, and physical demand was high. Insulin rose when food was available and fell when it was not. This rhythm allowed cells to respond efficiently without being overwhelmed.

Modern life has disrupted that balance. Food is constantly available, often in energy-dense and highly refined forms. Physical activity and movement is no longer required for daily survival. At the same time, sleep disruption, chronic stress, and irregular schedules raise the baseline demand for insulin even further.

Under these conditions, insulin signaling is required almost continuously. The hormone itself does not change, but the environment does. Over time, cells adapt by becoming less responsive, reducing how much energy they allow in. This adaptation protects the cell in the short term, but it comes at the cost of normal metabolic regulation.

This is the mismatch. The body is equipped to manage energy in cycles, but is instead placed in a state of constant input and low output. Insulin resistance is not a failure of willpower or a flaw in the hormone, but a predictable response to sustained imbalance.

Understanding metabolic disease through this lens changes the conversation. It shifts focus away from blaming individual nutrients or hormones and toward restoring alignment between energy intake, energy use, and recovery. Reducing metabolic pressure, increasing physical demand, and allowing periods of rest all help return insulin signaling to its intended rhythm.

When that balance is restored, insulin no longer needs to work overtime. Regulation becomes easier, responsiveness improves, and metabolic health begins to reassert itself. The solution is not to fight insulin, but to change the environment that forced it into constant use.

Reframing Insulin Correctly

By this point, insulin should look very different from the way it is often portrayed. It is not a fat-storage switch, a metabolic villain, or a hormone to fear. It is a regulator, doing the job it was designed to do in the conditions it is given.

Insulin exists to manage energy safely. It protects cells from excess glucose, coordinates how fuel is used and stored, and supports repair and recovery. These functions are not optional. They are fundamental to survival and long-term health.

Problems arise not because insulin is present, but because modern conditions force insulin signaling to remain elevated far too often. Constant food availability, low physical demand, chronic stress, and poor recovery place continuous pressure on a system designed to work in cycles. Insulin resistance is the predictable result of that mismatch.

This is why approaches that reduce insulin demand—such as low-carbohydrate diets or less frequent eating—often help. They give the system breathing room. But their success does not mean insulin is harmful, nor does it mean health requires avoiding insulin forever.

A healthier way to think about insulin is in terms of responsiveness, not suppression. In a well-functioning system, insulin rises when needed and falls when its work is done. Flexibility, not avoidance, is the goal.

Reframing insulin this way shifts the focus away from single nutrients or hormones and toward the broader context in which metabolism operates. It encourages strategies that reduce chronic overload, restore balance, and allow normal regulation to return.

Insulin did not break human metabolism. It has been responding to an environment that no longer matches the conditions it evolved to manage. Understanding that difference is the first step toward making choices that support metabolic health rather than fighting against it.

FAQs

What does insulin do in the body?

Insulin is a hormone that helps keep blood sugar within a safe range by moving glucose out of the bloodstream and into cells where it can be used for energy. Beyond blood sugar control, insulin also helps coordinate how energy is distributed, supports tissue repair, and protects organs from damage caused by prolonged high glucose levels.

What causes insulin resistance?

Insulin resistance develops gradually when cells are repeatedly exposed to more energy than they can comfortably manage. Over time, cells reduce their responsiveness to insulin as a protective adaptation, often influenced by chronic overnutrition, low physical activity, poor sleep, stress, and ongoing inflammation.

What happens if insulin is high?

High insulin levels usually indicate that the body is compensating to keep blood glucose stable when cells are less responsive to insulin. While this compensation can work for years, persistently elevated insulin signals ongoing metabolic strain and often accompanies insulin resistance rather than causing it.