Most nutrition debates start with food: carbohydrates versus fat, calories versus hormones, one diet versus another. But those arguments often skip a more fundamental question—how the body actually uses energy in the first place.

Human metabolism is the system that determines how carbohydrates, fat, and protein are processed, prioritized, stored, or converted into energy. It governs whether fuel is used immediately, saved for later, or invested in building and repair. Without understanding this system, discussions about diet tend to become oversimplified, contradictory, or ideological.

This article explains how human metabolism really works. You’ll learn how the body chooses between carbohydrates, fat, and protein, why glucose is tightly regulated, how fat provides long-term energy, when ketones are produced, and why metabolic flexibility (switching between glucose and ketones) matters for health. The goal is not to tell you what to eat, but to give you a clear framework for understanding why different dietary approaches affect people differently.

By the end, you’ll be able to evaluate nutrition claims with greater clarity, recognize where common misunderstandings come from, and understand the biological context behind many modern diet debates—before choosing any particular strategy.

What Metabolism Actually Is (and What It Isn’t)

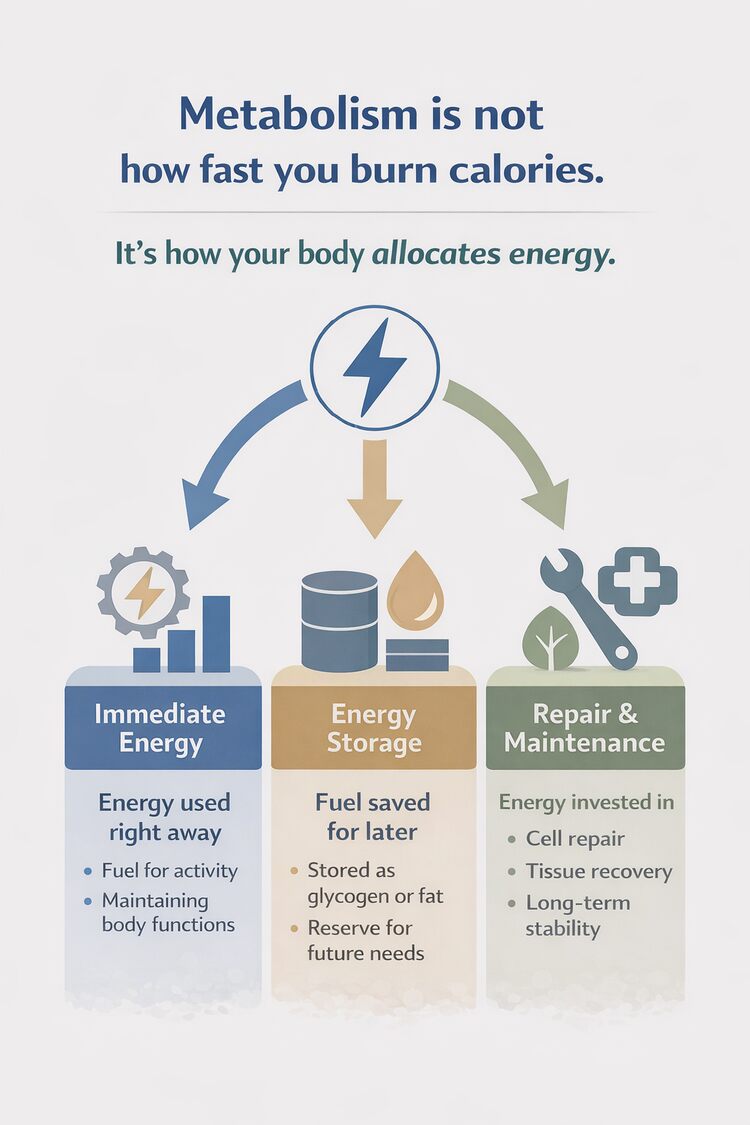

When most people talk about “metabolism,” they’re usually talking about weight and calorie burning. Someone has a “fast metabolism,” someone else has a “slow one,” and that difference is often blamed for how easily a person gains or loses fat.

In biology, metabolism means something much broader—and far more interesting.

Metabolism refers to the full collection of chemical processes that keep the body alive. These processes allow your cells to turn food into usable energy, repair and replace tissues, regulate body temperature, produce hormones, and power everything from muscle movement to brain activity. Metabolism doesn’t switch on when you eat and off when you stop—it runs continuously, even while you sleep.

You can think of metabolism as a budget. Energy from food is not simply taken in and spent, but deliberately allocated. Some is used immediately to meet current demands, some is saved for future needs, and some is invested in building, repair, and long-term maintenance.

While having more energy coming in than going out is necessary for survival, thriving depends on how that energy is managed. Metabolism is the system that sets those priorities—balancing short-term expenses with savings and long-term investments, all at the same time.

Metabolism Is a System, Not a Speed

We often describe metabolism as “fast” or “slow,” but that language oversimplifies what’s really happening. While people do differ in how much energy they burn at rest, metabolism isn’t just a dial that controls calorie burning.

A better analogy is a smart thermostat, not a furnace. The body constantly adjusts how energy flows based on current conditions—what you’ve eaten, how active you are, whether you’re stressed, and what different tissues need at that moment.

Two people can eat the same number of calories and experience very different outcomes because their bodies are making different decisions with that energy. A taller person may require more energy simply to maintain basic functions, an athlete may channel more energy toward movement and repair, while a sedentary individual may store more. Differences in sex, muscle mass, and hormonal environment further shape how that same intake is used.

The body doesn’t simply burn fuel because it’s available, like a car engine at idle. It allocates energy deliberately, prioritizing stability and survival over convenience.

Catabolism and Anabolism

All metabolic activity falls into two broad categories, which are always happening side by side:

- Catabolism is the process of breaking down molecules to release energy. This includes converting carbohydrates, fats, and—when necessary—proteins into usable energy that cells can spend immediately. You can think of

- Anabolism is the process of building and maintaining the body. This includes repairing muscle tissue, producing enzymes and hormones, and storing energy for future use.

You can think of catabolism as earning income and anabolism as paying bills and making investments. Energy is constantly coming in and going out, and the body has to balance both at once.

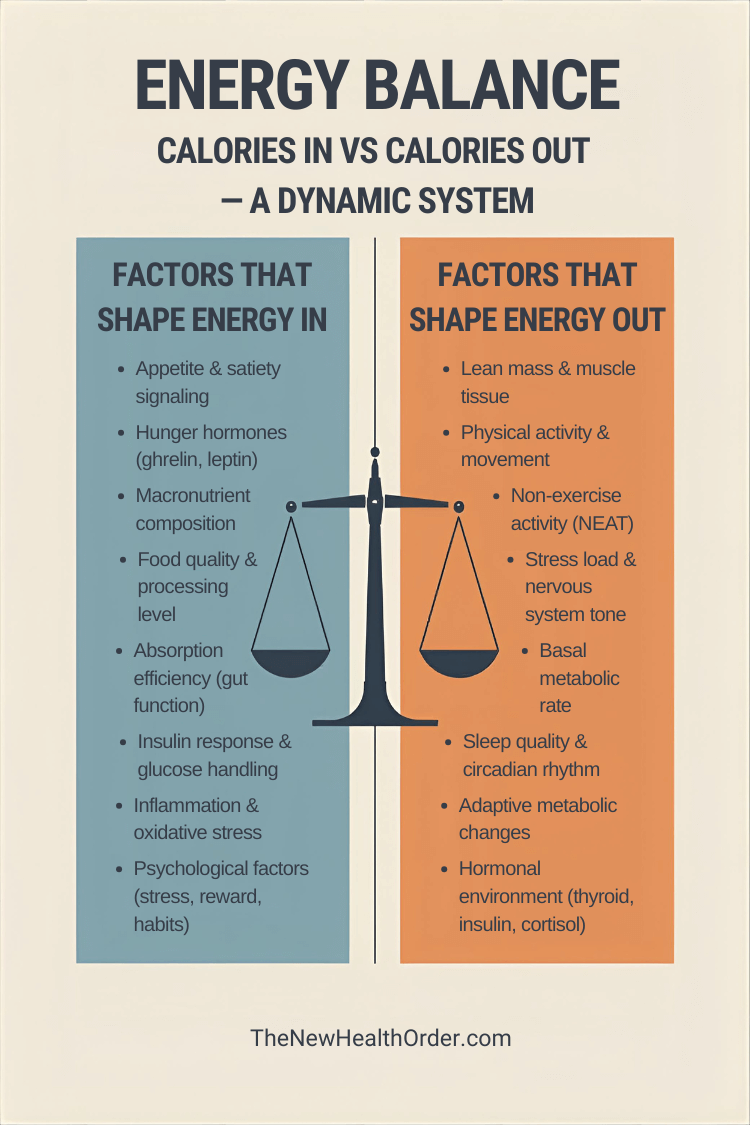

Calories Measure Energy, Not Instructions

This is why “calories in versus calories out” is not as simple as it sounds on the surface. The arithmetic itself is static—energy cannot be created or destroyed—but the biology that determines how many calories are actually burned is highly dynamic.

Energy expenditure is shaped by metabolism, which reflects many variables, including body size, muscle mass, activity level, hormonal signals, and how energy is being allocated at a given time. As a result, two people of similar stature can experience very different outcomes on the same intake—one losing weight at 2,500 calories while another gains weight at 1,500.

A large part of this variance is the fact that most of the energy your body uses each day isn’t from exercise — it’s from maintaining basic life processes. Basal metabolic rate (BMR), which supports breathing, circulation, and cell function, accounts for about 60–70% of daily energy expenditure, with the rest split between physical activity and the energy cost of digesting food.

Calories still matter, but metabolism determines calories out. It is the underlying metabolic context—not the math alone—that shapes real-world outcomes.

Metabolism is not a fixed “burn rate”, it is more of an adaptive, responsive, and highly regulated system that continuously adjusts how energy is used, stored, and allocated.

Rather than treating all calories or foods identically, metabolism responds to internal signals and external demands—such as activity, stress, feeding, and rest. It isn’t something you simply “have,” but something your body is constantly doing, recalibrating moment by moment to maintain stability and function.

How the Body Chooses Which Fuel to Use

The human body does not rely on a single fuel source. At any given moment, it draws energy from a combination of carbohydrates, fats, and—under specific conditions—protein. Which fuel contributes most depends on what is available and what the body needs right now.

And not all calories are processed the same. The energy cost of digesting food — the thermic effect of food — varies by macronutrient. Protein has a much higher thermic cost than carbohydrates or fat, meaning the body expends more energy simply processing protein.

Rather than thinking in terms of preference, it is more accurate to think in terms of priority. The body continuously prioritizes fuel use in a way that maintains stability and supports immediate demands while preserving longer-term energy reserves.

Some fuels are available to the body almost instantly. When carbohydrates are consumed, they are broken down into glucose, which enters the bloodstream and can be used quickly by many tissues. How quickly your glucose rises depends on the type of carbohydrate you eat. Because elevated blood glucose must be tightly regulated, glucose is typically dealt with promptly—either used for energy or stored.

Fat, by contrast, is stored primarily in adipose tissue (body fat) and is released more gradually. Accessing fat for energy requires additional steps and oxygen, but it provides a large and reliable supply of fuel over time.

This difference in availability plays a major role in how the body allocates energy from moment to moment.

Short-Term Needs vs Long-Term Energy

Fuel selection also reflects the body’s need to balance short-term energy demands with long-term planning.

Glucose (from carbohydrates) supports rapid responses and immediate activity. Ketones (from fat) support endurance and sustained energy use. Both serve essential roles, and neither is inherently dominant across all situations.

You can think of this as an energy budgeting system: some resources are kept readily accessible for quick use, while others are stored efficiently for later.

Mixed Fuel Use Is Normal

Even in a rested state, the body typically uses a mixture of fuels. After eating—particularly after carbohydrate intake—glucose contributes a larger share. Between meals, during sleep, or during prolonged low-intensity activity, fat often contributes more.

These shifts do not occur as sudden switches. Instead, the body continuously adjusts the balance between available fuels based on changing conditions. The ability to make these adjustments efficiently is sometimes referred to as metabolic flexibility, a very important concept that affects weight loss, health, and everything in between, which we will return to later.

Fuel use is not determined by conscious choice or willpower. It is guided by chemical signals—especially hormones—that reflect the body’s current state. These signals influence whether energy is used immediately, stored for later, or released from storage.

At this stage, it’s enough to understand that fuel selection is regulated and context-dependent. The details of those regulatory signals become clearer when we examine how each macronutrient is processed.

Carbohydrate Metabolism

When carbohydrates are present, they play a prominent role in short-term energy regulation. Once eaten, they are processed into glucose, a form of energy that can be used quickly by many tissues. Because glucose levels in the blood must be tightly controlled, the body handles carbohydrates in a highly regulated way.

What Happens to Carbohydrates After You Eat Them

Most dietary carbohydrates, whether they come from sugars or starches, are broken down during digestion into simple sugar units—primarily glucose (carbohydrates are just long chains of sugar molecules). This glucose is absorbed through the intestinal wall and enters the bloodstream.

Once in circulation, glucose becomes immediately available as an energy source. At this point, the body must decide how to handle it. Broadly, there are three options: use it right away to meet current energy needs, store it for short-term use, or redirect it into other metabolic pathways.

Which option is chosen depends on factors such as current activity level, hormonal signals, and how much stored energy is already available.

A common misconception is that glucose comes only from dietary carbohydrates. While carbohydrates are one source of glucose, they are not the only one. The body is capable of producing glucose on its own through regulated metabolic pathways, supplying what is needed for normal function even when dietary carbohydrate intake is low. This ability allows the body to maintain stable energy availability without placing undue burden on any single fuel source.

Glycogen Storage in Liver and Muscle

When immediate energy demands are met, excess glucose can be stored as glycogen. Glycogen is a storage form of glucose found primarily in the liver and skeletal muscle.

These two storage sites serve different purposes:

- Liver glycogen helps maintain blood glucose levels between meals.

- Muscle glycogen provides fuel for muscle contraction during physical activity.

Glycogen storage, however, is limited. Once these stores are filled, additional glucose must be handled differently. This limited capacity is one reason carbohydrate metabolism behaves differently from fat metabolism, which relies on much larger storage reserves.

Why Glucose Is Closely Regulated

Unlike fat, glucose cannot accumulate freely in the bloodstream. Even modest elevations outside the normal range can interfere with cellular function, so the body uses hormonal signals—most notably insulin—to keep blood glucose within tight limits (see this article here for an in-depth look at metabolism’s most crucial hormone – insulin).

Rather than allowing glucose to linger in circulation, the body directs it toward immediate use or storage as efficiently as possible. The goal is not to favor carbohydrates over other fuels, but to maintain internal stability.

Many mainstream explanations describe glucose as the body’s “preferred” fuel, implying that it is inherently superior to other energy sources. In reality, glucose is often used promptly not because it is a better fuel, but because it must be tightly regulated. Once glucose enters circulation, the body has limited options: it must be used, stored, or converted. Immediate use or short-term storage is therefore the most practical way to manage its presence.

Glucose and glycogen provide short-term energy buffering, not long-term energy storage. Once glycogen stores begin to decline—such as between meals or overnight—the body gradually shifts toward other fuel sources to meet ongoing energy needs.

Seeing carbohydrate metabolism in this context helps clarify its role: glucose is a fast, tightly regulated fuel that supports immediate demands, especially when the body must tightly regulate glucose levels, while other fuels contribute over longer time frames.

For a full look at carbohydrates, and exactly how they can affect health and energy (for better or worse), see this article here.

Glucose and Glycogen at a Glance

| Feature | Glucose | Glycogen |

| Circulates in blood | Yes | No |

| Must be tightly regulated | Yes | Yes |

| Storage location | Bloodstream | Liver & muscle |

| Storage capacity | Very limited | Limited (hours–day) |

| Primary role | Immediate energy | Short-term buffer |

Fat Metabolism (Fatty Acids and Ketones)

Fat is handled by the body very differently from carbohydrates. Rather than circulating freely as a rapid-use fuel, fat is primarily stored and accessed deliberately over time. This makes fat the body’s most reliable long-term energy reserve.

How Dietary Fat Is Processed and Stored

Dietary fats are broken down during digestion into fatty acids and glycerol. These components are absorbed through the intestinal wall and transported in the bloodstream to tissues throughout the body.

Most fatty acids are directed toward storage in adipose tissue, where they are assembled into triglycerides. This storage system is highly efficient and allows the body to maintain large energy reserves without disrupting normal blood chemistry.

Unlike glucose, fatty acids are not allowed to accumulate freely in the bloodstream. Their release from storage is tightly regulated, ensuring that fat remains a stable and controlled energy source rather than a constantly circulating one.

Whereas glycogen stores are limited and deplete relatively quickly, fat stores are large and can sustain energy needs for much longer periods. It has been documented multiple times that with enough stored fat, the body can survive for weeks and months without consuming any calories. In fact, the longest medically documented fast without food is 382 days, achieved by Angus Barbieri in 1965-1966.

Fatty Acid Oxidation and Energy Production

When energy demand increases and conditions allow, fatty acids are released from adipose tissue (body fat) and transported to cells. Inside the mitochondria, these fatty acids are broken down through a process known as fatty acid oxidation (often called beta-oxidation).

Compared to glucose metabolism, fatty acid oxidation requires oxygen, produces energy more slowly, but yields a large amount of energy per unit of fuel.

This makes fat particularly well suited for sustained, lower-intensity energy needs rather than rapid bursts of activity. Over longer timeframes—such as between meals, during sleep, or during prolonged activity—fat can supply a substantial portion of the body’s energy requirements, even when food is scarce.

Ketones as an Alternative Fuel Source

When fat is broken down for energy, most tissues can use the resulting fatty acids directly. However, some tissues—most notably parts of the brain—cannot rely on fatty acids as a primary fuel. To bridge this gap, the body has an additional mechanism.

Under certain metabolic conditions, the liver converts some fatty acids into ketone bodies, commonly referred to as ketones. Ketones are small, water-soluble molecules that circulate easily in the bloodstream and can be used as an energy source by many tissues, including the brain.

Ketone production increases when glucose availability is lower and fat mobilization is higher, such as between meals, during fasting, or when carbohydrate intake is reduced. In these situations, ketones allow energy stored as fat to be used more broadly throughout the body, rather than being limited to tissues that can oxidize fatty acids directly.

Importantly, ketones are not a separate or emergency system, nor do they replace glucose entirely. They are a normal extension of fat metabolism that helps maintain energy availability across different conditions. By providing an additional, flexible fuel source, ketones extend the usefulness of stored fat and support metabolic continuity when glucose supply is reduced.

For a deeper dive into how ketones and ketosis change the physiology of the body, see this article here.

Fat Within the Broader Energy System

Fat metabolism operates alongside carbohydrate metabolism, not in opposition to it. The body continuously adjusts how much energy comes from fat versus glucose based on availability, demand, and regulatory signals.

Because fat stores are large and stable, fat metabolism plays a key role in maintaining energy supply over longer periods. This contrasts with glucose and glycogen, which support shorter-term energy buffering.

Protein Metabolism

Protein plays a fundamentally different role in human metabolism than carbohydrates or fats. Rather than functioning primarily as a fuel, protein supplies the raw materials needed to build, repair, and regulate the body. Energy production from protein is possible, but it is not the body’s preferred use for this macronutrient.

The Primary Roles of Protein in the Body

Dietary proteins are broken down during digestion into amino acids, which enter a shared amino acid pool in the body. From this pool, amino acids are used to support a wide range of essential functions, including:

- Building and repairing muscle and connective tissue

- Producing enzymes that drive metabolic reactions

- Forming hormones and signaling molecules

- Supporting immune function and cellular maintenance

Unlike carbohydrates and fats, protein does not have a dedicated storage form. The body maintains only a limited circulating amino acid pool, which must be continually replenished through dietary intake or internal recycling.

Because of these roles, protein availability shapes how well the body recovers from activity, maintains muscle and connective tissue, and supports everyday functions like immune defense and hormone production.

Why Protein Is Not a Preferred Energy Source

Although amino acids can be used for energy, the body avoids doing so when other fuels are available. Using protein for energy requires additional processing steps, including the removal of nitrogen, which must then be safely excreted.

This makes protein a metabolically costly fuel compared to glucose or fatty acids. More importantly, diverting protein toward energy production reduces the amino acids available for their primary structural and regulatory roles.

For this reason, protein contributes only a small share of total energy under most conditions, with carbohydrates and fats supplying the majority of fuel.

Gluconeogenesis and Conditional Energy Use

Under certain conditions, the body can convert some amino acids into glucose through a process called gluconeogenesis. This pathway helps maintain blood glucose levels when carbohydrate availability is low.

Gluconeogenesis does not occur exclusively from protein, nor does it operate at a fixed rate. It is a regulated, demand-driven process influenced by energy status and hormonal signals.

Importantly, gluconeogenesis does not mean that dietary protein is automatically converted into glucose. Instead, it reflects the body’s ability to maintain glucose availability when needed, using multiple possible substrates. When available, most glucose production is supported by non-protein sources—such as glycerol from fat metabolism and recycled lactate—allowing essential glucose needs to be met without excessive reliance on protein.

Protein’s primary function is to maintain the body’s structure and regulatory systems. Its role as an energy source is conditional and supportive, not central.

Primary Fuels and Their Roles

| Fuel | Main Role | Speed of Use | Storage Capacity | Typical Context |

| Glucose | Rapid energy | Fast | Limited (glycogen) | Fed state, high demand |

| Fatty acids | Sustained energy | Slower | Large | Between meals, rest |

| Ketones | Extended fuel support | Moderate | Derived from fat | Low glucose availability |

| Protein | Structural support | Inefficient | No storage | Energy backup only |

Metabolic Flexibility and Fuel Switching

Human metabolism is not designed to rely on a single fuel source at all times. Instead, it is built to move between fuels as conditions change. This ability to shift between glucose- and fat-based energy is known as metabolic flexibility.

In daily life, energy availability naturally fluctuates. After eating, glucose from food enters circulation. As time passes between meals, that supply tapers off. Overnight, the body relies almost entirely on stored energy. A flexible metabolic system adapts to these transitions smoothly.

This switching is necessary in part because of how energy is stored. Glycogen—the stored form of glucose—acts as a short-term buffer, but its capacity is limited. Fat, by contrast, is stored in far larger quantities and represents the body’s primary long-term energy reserve. As glycogen declines, the body naturally increases its reliance on stored fat. This is not a failure of carbohydrate intake; it is the intended design of the system.

As fat mobilization increases, the liver converts some fatty acids into ketone bodies. Ketones allow energy stored as fat to be used by tissues that cannot rely on fatty acids alone, including parts of the brain. But ketones are more than a backup fuel. Entering a ketone-supported state also changes the body’s hormonal and signaling environment.

When insulin and glucose levels are consistently high, metabolism remains biased toward storage and growth. Periods of ketosis shift the system in a different direction—toward maintenance, repair, and metabolic efficiency. Certain regulatory processes become more active in this state, while constant growth signaling is temporarily dialed down. These effects are not simply about energy delivery; they reflect a different operating mode of the body.

Metabolic flexibility, then, is not just about being able to switch fuels in an emergency. It includes the ability to enter and benefit from fat- and ketone-supported states from time to time. In modern environments where carbohydrates are always available, this state is no longer required for survival—but it may still matter for long-term metabolic health.

Seen this way, ketosis is not an obsolete adaptation or a spare system kept in reserve. It is part of the body’s normal regulatory range, offering benefits that are difficult to access when insulin remains elevated continuously. Human metabolism evolved to move between these states, not to remain locked in just one.

Hormones and Metabolism

Metabolism is not governed by calories or macronutrients alone. It is regulated by a network of hormonal signals that coordinate how energy is used, stored, and released across the body.

Hormones act as messengers. They reflect the body’s current state—fed or fasted, active or resting, stressed or calm—and adjust metabolic pathways accordingly. In this way, hormones translate changing conditions into metabolic decisions.

Among the most influential metabolic hormones is insulin, which signals that energy is available and promotes the uptake and storage of nutrients. Its counterpart, glucagon, signals energy scarcity and supports the release of stored fuels. Together, they help maintain stable blood glucose and coordinate fuel availability.

Other hormones play supporting but important roles. Thyroid hormones influence overall energy throughput, affecting how rapidly fuels are processed. Stress hormones, such as cortisol and adrenaline, help mobilize energy during acute demand. Longer-term signals, including hormones involved in appetite and energy balance, help align intake with expenditure over time.

Crucially, hormones do not act in isolation. Metabolic regulation emerges from their combined effects, varying by tissue and circumstance. The same nutrient can be handled differently depending on the surrounding hormonal environment.

Understanding metabolism therefore requires more than knowing what fuels exist or how they are processed. It requires recognizing that fuel use is governed by signals, not by conscious choice or static rules.

This hormonal layer is what allows metabolism to remain adaptive—responding appropriately to changing conditions rather than operating rigidly.

Key Hormones in Metabolic Regulation

| Hormone | Primary Signal | Effect on Metabolism |

| Insulin | Energy abundance | Storage, uptake |

| Glucagon | Energy scarcity | Fuel release |

| Cortisol | Stress | Mobilization |

| Thyroid hormones | Throughput | Energy rate |

| Adrenaline | Acute demand | Rapid fuel access |

Why Understanding Metabolism Matters Before Choosing a Diet

Most discussions about diet begin at the wrong level. They focus on food choices, macronutrient ratios, or rules to follow, without first establishing how the body actually processes and regulates energy.

Metabolism is the system that sits beneath every dietary approach. It determines how carbohydrates, fats, and proteins are handled, how fuels are prioritized, and how the body adapts as conditions change. Without understanding this system, dietary arguments tend to become ideological rather than biological.

This is why the same diet can produce different outcomes in different people, and why no single macronutrient framework explains metabolic health on its own. Food does not act on a blank slate. It enters an already regulated system shaped by hormones, energy status, and prior conditions.

Understanding metabolism does not tell you what to eat. It tells you how the body responds to what is eaten. That distinction matters because it shifts the conversation away from rigid prescriptions and toward mechanism, context, and adaptability.

By starting with metabolism, later discussions about diet, health, and metabolic dysfunction can be grounded in physiology rather than assumption. The goal is not to promote a particular way of eating, but to provide a framework that makes nutritional claims easier to evaluate—and harder to oversimplify.

FAQs

What is metabolism, in simple terms?

Metabolism is not just a measure of how fast you burn calories or how easily you lose weight. It is the entire system that manages how energy is used, stored, and allocated throughout the body. This includes powering cells, maintaining body temperature, repairing tissues, producing hormones, and deciding whether energy is spent immediately or saved for later. Weight change is only one possible outcome of how this system is regulated.

Does the body prefer carbs over fat for energy?

The body doesn’t prefer carbohydrates because they are a “better” fuel. Instead, glucose from carbs must be tightly regulated in the bloodstream, so when it is present, the body prioritizes using or storing it to maintain stability. Fat is stored in much larger quantities and released more gradually, making it a more suitable long-term fuel. Which fuel dominates depends on availability and hormonal signals, not preference.

Can the body make glucose without eating carbohydrates?

Yes. The body can produce glucose on its own through regulated metabolic pathways, a process known as gluconeogenesis. This allows essential tissues that rely on glucose to function even when dietary carbohydrates are limited. Importantly, this process is demand-driven and uses multiple possible substrates, meaning the body can maintain necessary glucose levels without requiring constant carbohydrate intake.