Carbohydrates are one of the most common sources of dietary energy, yet their effects are often discussed in broad or conflicting terms. Some people report stable energy and good performance when eating carbohydrates, while others experience fatigue, hunger, or difficulty regulating blood sugar. These differences are frequently attributed to the carbohydrates themselves.

In reality, carbohydrates follow the same basic physiological pathway in everyone. They are digested, absorbed as glucose, and managed through a coordinated hormonal response. What differs is not the food, but how the body handles it once glucose enters the bloodstream.

This article explains what happens in the body after carbohydrates are eaten, step by step—from digestion and absorption, to insulin release, to how glucose is ultimately used or stored. Rather than asking whether carbohydrates are “good” or “bad,” the focus is on understanding the process so individuals can recognize how carbohydrates affect their own bodies, instead of adopting rules that may work well for others but not for them.

What Happens in Your Body When You Eat Carbohydrates

When carbohydrates are eaten, the body processes them in a predictable sequence. First, they are broken down and absorbed into the bloodstream. Next, hormones respond to manage rising blood sugar. Finally, glucose is directed toward use or storage. While the later stages depend heavily on metabolic health, the early steps are largely the same for everyone.

For a full walk-through of exactly what carbs are, see this article here.

Step 1 — Carbohydrates are Digested and Absorbed

Before carbohydrates can influence energy levels, hormones, or fat storage, they must first be broken down from the food we eat into absorbable units that can be delivered into the bloodstream. This initial phase of carbohydrate handling is remarkably consistent across individuals. Regardless of health status, fitness level, or dietary philosophy, the body follows the same basic steps.

What differs later is not whether this process occurs, but how the body responds once glucose enters circulation.

Breakdown into Simple Sugars

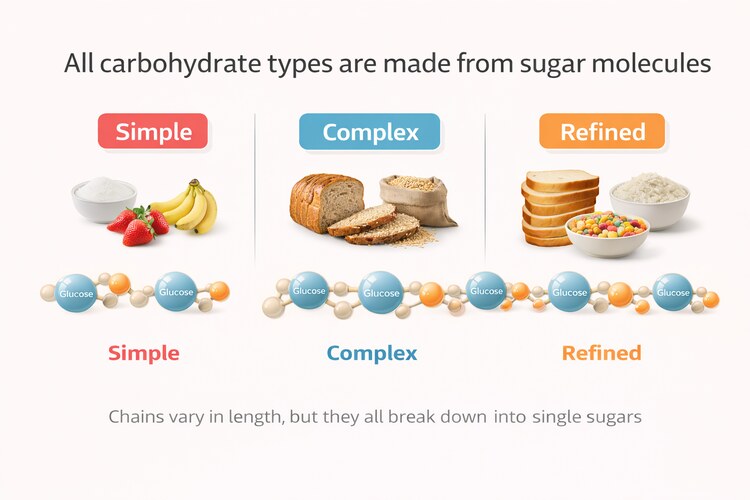

Carbohydrate digestion begins in the mouth. Enzymes in saliva, primarily amylase, start breaking large carbohydrate structures like starches into smaller chains (all carbohydrates break down into small sugars like glucose). This early step is limited but important, as it prepares carbohydrates for more complete digestion later on.

When food reaches the stomach, carbohydrate digestion largely pauses. This is not because the stomach fails to digest food, but because its environment is optimized for a different task. The stomach is highly acidic, which is ideal for protein denaturation and pathogen control, but incompatible with carbohydrate-digesting enzymes. As a result, salivary amylase is inactivated, and carbohydrate digestion temporarily slows.

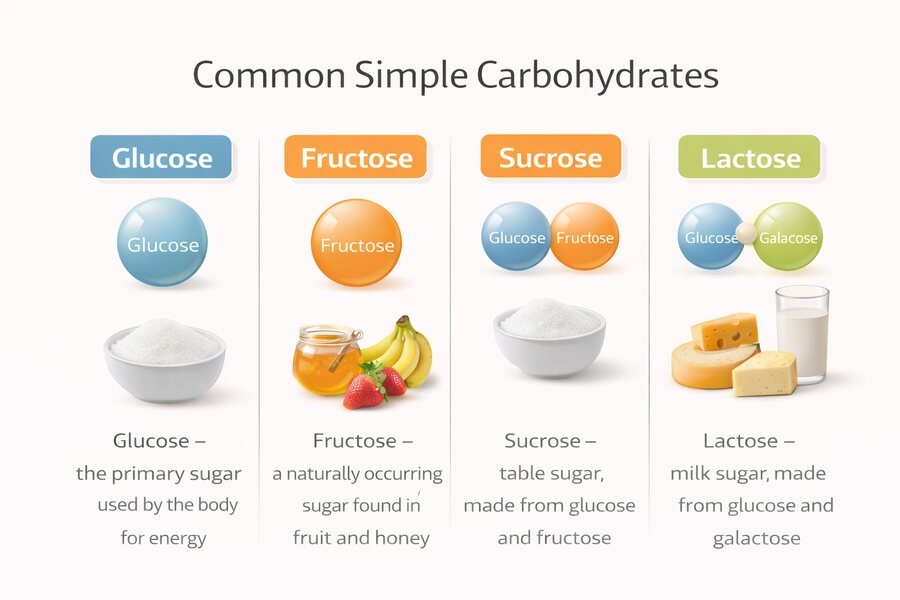

The process picks up again in the small intestine, however. Here, pancreatic enzymes continue breaking carbohydrate chains down until they reach their simplest usable forms: monosaccharides. The primary monosaccharide produced is glucose, along with smaller amounts of fructose and galactose. These single-sugar units are the only forms carbohydrates can be absorbed as; anything more complex cannot cross the intestinal wall.

By this point, the original food source matters far less than many people assume. Whether carbohydrates come from fruit, grains, legumes, or refined foods, they must ultimately be reduced to the same basic sugars before the body can use them. Differences in food quality influence how quickly this happens (which is very important for health), but not what the end product is.

Absorption into the Bloodstream

Once carbohydrates have been fully broken down, glucose is absorbed through the lining of the small intestine and enters the bloodstream. This moment marks the point at which carbohydrates become metabolically relevant.

As glucose appears in circulation, blood sugar levels rise. This rise is not abnormal, dangerous, or pathological—it is the expected and necessary consequence of eating carbohydrate-containing foods. The body is designed to detect this increase quickly and respond to it in a controlled and coordinated way.

It is important to understand that the bloodstream is not the final destination for glucose. It functions as a temporary transport system, allowing energy to be delivered from the gut to tissues throughout the body. Elevated blood glucose is meant to be transient, not sustained.

Why Blood Glucose Rises

The rise in blood glucose following carbohydrate intake serves a clear physiological purpose: it signals that energy is available. This signal initiates the next phase of carbohydrate handling, in which hormones coordinate how that energy is distributed, stored, or used.

At this stage, nothing has gone “wrong.” No fat has been stored by default. No metabolic damage has occurred. The body is simply recognizing incoming fuel and preparing to manage it.

What determines whether this process unfolds smoothly, or becomes problematic, depends on what happens next.

Step 2 — Insulin is Released

As glucose enters the bloodstream after carbohydrate absorption, the body responds by releasing insulin. This response is rapid, automatic, and necessary. Insulin is not released because something has gone wrong, but because glucose is not meant to remain in the blood for long.

Glucose is a useful fuel inside cells, but when it lingers in circulation it quickly becomes harmful. Prolonged elevation increases oxidative stress and promotes chemical reactions that damage proteins and tissues. For this reason, the body treats rising blood glucose as a temporary state that must be corrected.

Insulin provides the signal that allows glucose to be cleared from the bloodstream and delivered into cells that can use or safely store it. In this sense, insulin is protective. It restores balance by moving energy to where it belongs.

How Insulin Release is Triggered

The pancreas is constantly sensing how much glucose is circulating in the blood. When glucose levels begin to rise after a meal, pancreatic cells respond almost immediately by releasing insulin. In a healthy system, this response begins within minutes.

The digestive tract also plays a role. As carbohydrates move through the intestine, hormonal signals are released that alert the pancreas in advance, allowing insulin levels to rise early, rather than waiting until blood sugar has already climbed too high. In metabolically healthy individuals, insulin release often starts before blood glucose reaches its peak, helping to keep the rise controlled and short-lived.

What Insulin Actually Does

Insulin is often described as a “fat storage hormone,” but this framing is incomplete and misleading. In the context of a normal meal, insulin functions primarily as a coordination signal.

It directs glucose out of the bloodstream and into tissues that can use it immediately or store it safely. Muscle cells increase glucose uptake for energy or glycogen replenishment. The liver absorbs glucose and reduces its own glucose output. As a result, blood sugar levels fall back toward baseline.

Fat storage is not the default outcome of insulin release – it occurs only when glucose cannot be efficiently used or stored elsewhere, or when energy intake consistently exceeds demand.

Timing of the Insulin Response

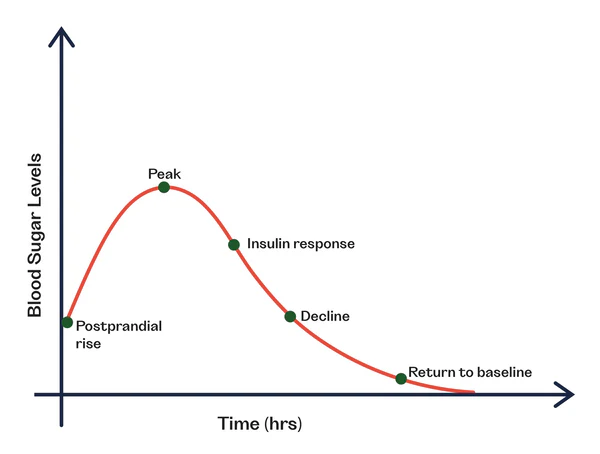

In a healthy person consuming a moderate carbohydrate meal, insulin release begins within minutes, peaks within roughly an hour, and declines as blood glucose returns toward baseline. Most glucose is cleared from circulation within one to two hours.

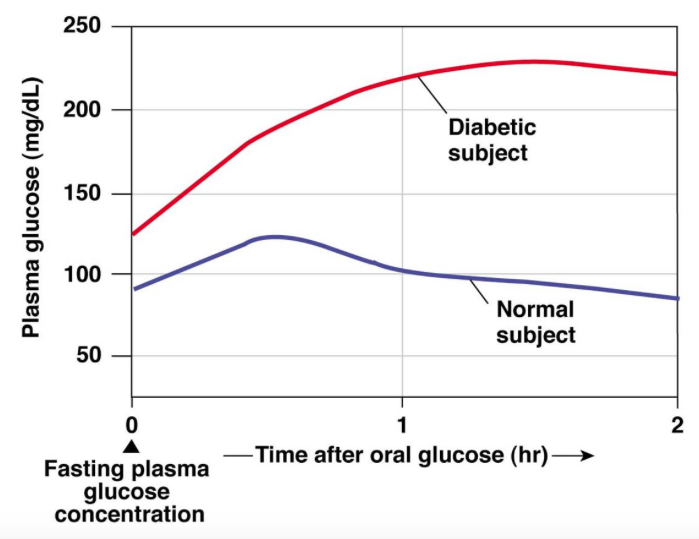

In a healthy system, blood glucose typically rises to ~120–140 mg/dL before insulin facilitates its return to baseline within about 2 hours.

Insulin secretion is fast, but it is not unlimited. The body releases enough insulin to restore balance, not the maximum amount possible. Very large or rapidly delivered glucose loads from carbohydrate-heavy meals can raise blood sugar higher and extend the time required for clearance, even in healthy individuals.

What defines metabolic health is not how much insulin can be produced in a single moment, but how efficiently glucose is cleared once insulin is released.

Step 3 — Where Carbohydrates Go in the Body

Once glucose begins to leave the bloodstream under the direction of insulin, the critical question is no longer whether carbohydrates are being handled, but how they are being handled. This process, known as nutrient partitioning, determines the ultimate fate of incoming glucose.

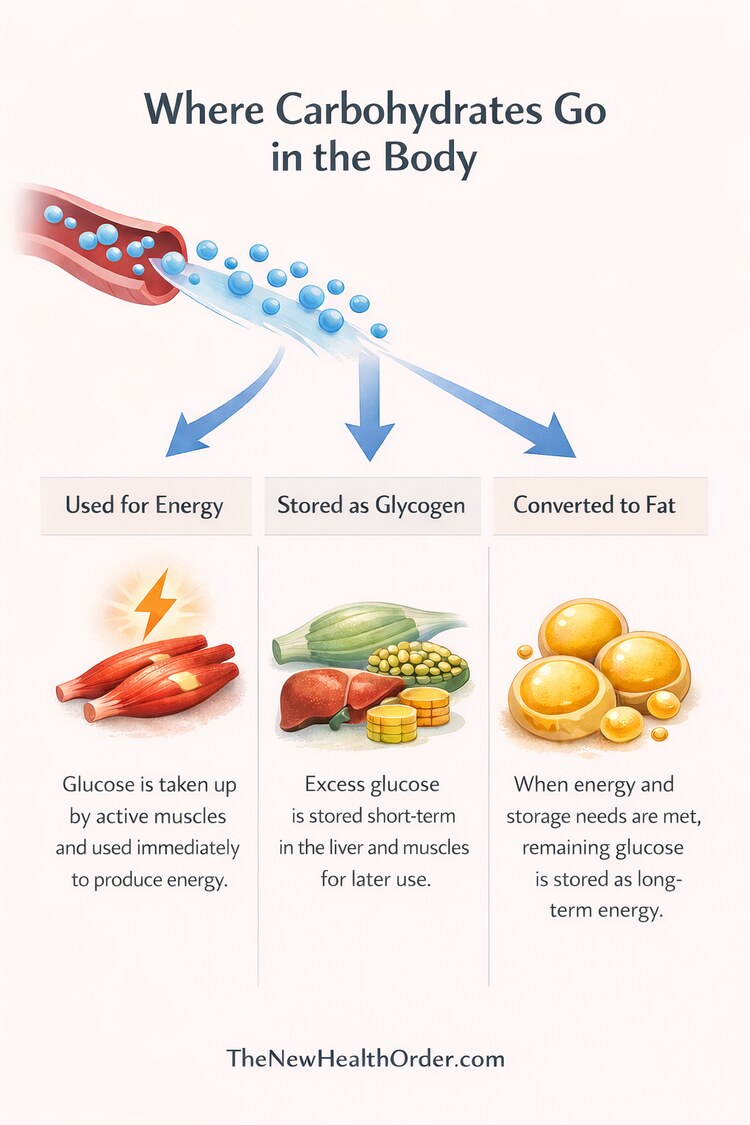

Glucose has only a few possible destinations. It can be used immediately for energy, stored temporarily for later use, or converted into fat. These pathways exist in everyone. What differs is which pathway dominates.

Used for Immediate Energy

When energy demand is high, glucose is pulled directly into active tissues, particularly skeletal muscle, and oxidized for fuel. This is the most direct and efficient use of carbohydrates and the one we most commonly think of – direct usable energy.

In physically active or metabolically healthy individuals, muscle acts as a powerful glucose sink, sucking up much of this free glucose. Insulin sensitivity is high, uptake is rapid, and glucose is cleared from the bloodstream quickly. In this context, carbohydrates support performance, recovery, and normal metabolic function rather than storage.

Stored as Glycogen for Later Use

When immediate energy needs are met, glucose can be stored as glycogen in muscle and liver cells. Glycogen acts as a short- to medium-term energy reserve that can be drawn on during physical activity or between meals.

This storage pathway is finite but flexible. The liver typically holds around 80–100 grams of glycogen, which is used primarily to maintain stable blood sugar when dietary glucose is unavailable. In a resting, non-exercising adult, liver glycogen can be substantially depleted within 12–24 hours, and much sooner during fasting, illness, or prolonged physical activity.

Muscle glycogen storage is larger—often 300–500 grams depending on muscle mass and training status—but it is stored locally and cannot be released back into the bloodstream. Instead, muscle glycogen is reserved for the muscle’s own energy needs.

Interestingly, studies show that immediate carbohydrate intake after exercise increases muscle glycogen repletion more than frequent small intakes, while smaller frequent intakes enhance liver glycogen stores.

Efficient glycogen storage allows carbohydrates to be absorbed and cleared from the bloodstream without prolonged elevations in blood glucose or insulin. When glycogen capacity is available, glucose has a clear destination. When it is not, the body must rely more heavily on other disposal pathways.

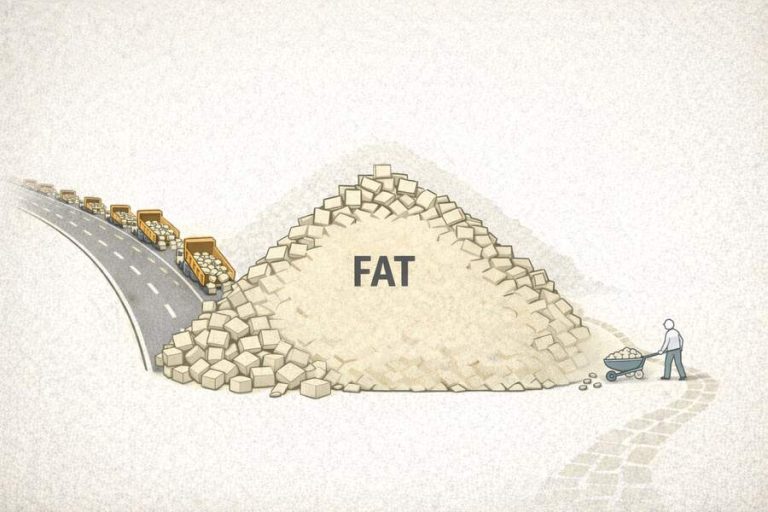

Converted to Fat

Conversion of glucose into fat is not the default outcome of carbohydrate intake. It becomes relevant when glucose cannot be efficiently used for energy or stored as glycogen.

In this situation, excess glucose must still be removed from circulation, and converting it into fat provides a safe long-term storage solution, preventing prolonged exposure of tissues to elevated blood sugar. This pathway reflects limited disposal capacity, not a flaw in carbohydrate metabolism itself.

Whether this pathway is engaged depends on metabolic context—particularly muscle insulin sensitivity, activity level, and overall energy balance.

The three possible destinations for glucose

| Destination | What It Means | When It Dominates |

| Immediate energy | Glucose is oxidized for fuel | High activity or energy demand |

| Glycogen storage | Glucose stored short-term in liver or muscle | Energy needs met, storage available |

| Fat storage | Glucose converted to long-term storage | Disposal capacity exceeded |

Why the Same Carbohydrates Produce Different Outcomes

By the time glucose has entered the bloodstream and insulin has been released to manage it, the original source of the carbohydrates is no longer the determining factor.

In a metabolically healthy body, this process is efficient and coordinated. Insulin sensitivity is high, particularly in skeletal muscle, which allows glucose to be taken up quickly and either used for energy or stored as glycogen. Blood sugar rises modestly, insulin exposure is brief, and levels return to baseline without much disruption. In this context, carbohydrates function as a useful fuel rather than a metabolic burden.

In a metabolically impaired body, the same sequence unfolds very differently. Muscle tissue responds poorly to insulin, glucose uptake is slower, and clearance from the bloodstream is delayed. At the same time, the liver may continue releasing glucose when it should be suppressing output. The result is higher blood sugar peaks, longer exposure, and prolonged insulin release. More glucose is directed toward storage pathways, not because carbohydrates are inherently fattening, but because the body lacks efficient alternatives.

These differences explain why population-wide nutrition advice often feels contradictory. Carbohydrates can support performance, recovery, and normal energy regulation in one person, while contributing to fatigue, hunger, and fat gain in another. The food has not changed. The metabolic context has.

This also explains why carbohydrate tolerance often tracks with activity level. Regular muscle use maintains insulin sensitivity and creates ongoing demand for glucose. When that demand disappears—through inactivity, aging, or chronic overconsumption—the same carbohydrate intake can overwhelm disposal capacity.

The important point is not that carbohydrates are “good” for some people and “bad” for others. It is that carbohydrates expose the state of the system handling them. They reveal metabolic health rather than define it.

How metabolic context changes carbohydrate handling

| Feature | Metabolically Healthy | Metabolically Impaired |

| Glucose uptake | Fast, efficient | Slower, impaired |

| Insulin exposure | Brief | Prolonged |

| Glycogen use | Favored | Limited |

| Fat storage | Secondary | More likely |

| Subjective effect | Stable energy | Hunger, fatigue, crashes |

Understanding this removes much of the confusion surrounding carbohydrates. They do not produce fixed outcomes. They produce responses that reflect how well the body is prepared to manage them.

For a deeper dive into insulin and its different response to metabolically healthy and unhealthy people, see this article here.

Why Some Feel Energized by Carbs—and Others Don’t

The way carbohydrates affect energy, hunger, and mood is not random. It reflects how efficiently the body handles glucose once it enters the bloodstream.

When glucose is cleared quickly and smoothly, energy tends to feel stable. Hunger stays muted for longer, and mood remains even. This is what carbohydrate intake looks like in a metabolically healthy system: fuel comes in, is used or stored appropriately, and the system returns to balance without much disturbance.

When glucose clearance is slower, the experience is very different. Blood sugar rises higher and stays elevated longer, followed by a stronger insulin response. As glucose is eventually cleared, levels can fall rapidly relative to the peak, triggering hunger, fatigue, irritability, or mental fog. These sensations are often described as “crashes,” but they are better understood as delayed correction.

Importantly, these effects are not driven by willpower or food quality alone. They are the downstream consequences of how efficiently glucose is managed. Two people can eat the same meal and walk away with entirely different experiences—one feeling energized and satisfied, the other feeling tired and hungry soon after.

This is why carbohydrate advice often feels inconsistent. Some people feel better eating carbohydrates when they match a real physiological demand (such as athletes and the energetically active), while others feel worse when those same carbohydrates exceed their capacity to handle them. Both experiences arise from the same underlying mechanisms.

Understanding this reframes the issue. If carbohydrates consistently disrupt energy or appetite, the problem is not a lack of discipline or a “bad” food choice. It is a signal that the system handling those carbohydrates is under strain.

For those interested in what exactly happens in the body when you don’t eat carbohydrates, see this article here.

Carbohydrates Reflect Metabolic State—They Don’t Define it

By this point, it should be clear that carbohydrates are not acting in isolation. They do not impose a single outcome on the body. Instead, they reveal how well the systems responsible for handling energy are functioning.

When carbohydrate intake is followed by stable energy, controlled appetite, and a smooth return to baseline, it reflects efficient glucose handling. When the same intake leads to fatigue, hunger, or prolonged blood sugar disruption, it points to limitations in clearance, storage, or coordination. In both cases, carbohydrates are exposing the state of the system, not causing it.

This is why repeated carbohydrate intake tends to amplify existing patterns rather than create new ones. In metabolically healthy individuals, regular carbohydrate exposure reinforces efficient handling. Muscle remains insulin sensitive, glucose is disposed of quickly, and balance is easily restored. In metabolically impaired individuals, repeated exposure prolongs insulin elevation, reinforces poor partitioning, and deepens dysfunction over time.

Seen this way, carbohydrates are signals. They provide feedback. They show whether energy is being used, stored temporarily, or diverted into long-term storage. They are not moral choices, dietary failures, or badges of discipline. They are inputs interacting with a system that may or may not be prepared to handle them.

This perspective resolves much of the confusion surrounding carbohydrate advice. There is no universal rule that applies to everyone at all times. There is only the interaction between carbohydrate intake and metabolic capacity at a given moment.

The most useful question, then, is not “Are carbohydrates good or bad?”

It is “How does my body respond when I eat them?”

Understanding that response—rather than following rigid rules—creates the space for meaningful change.

FAQs

What happens in your body when you eat carbohydrates?

When you eat carbohydrates, they are digested into simple sugars—primarily glucose—which enter the bloodstream. Rising blood glucose triggers insulin release, allowing glucose to be moved into cells where it can be used for energy, stored as glycogen, or directed toward longer-term storage depending on the body’s current needs and metabolic capacity.

Do carbohydrates automatically turn into fat?

No. Carbohydrates are first prioritized for immediate energy use and short-term storage as glycogen in the liver and muscles. Conversion of glucose into fat occurs only when energy demand is low and glycogen storage capacity is already full, making fat storage a secondary pathway rather than the default outcome.

Why do carbohydrates affect people differently?

Carbohydrates affect people differently because insulin sensitivity, muscle activity, and metabolic health determine how efficiently glucose is cleared from the bloodstream. In individuals with good glucose handling, carbohydrates are used or stored efficiently. In those with impaired clearance, the same carbohydrates can lead to prolonged blood sugar elevation, higher insulin exposure, and different subjective effects.