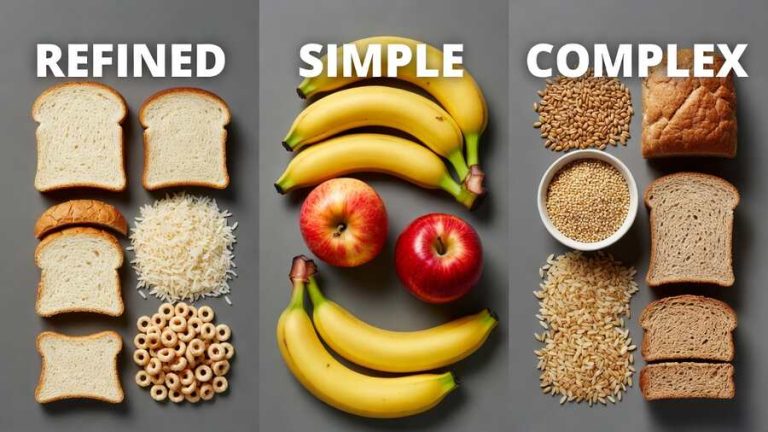

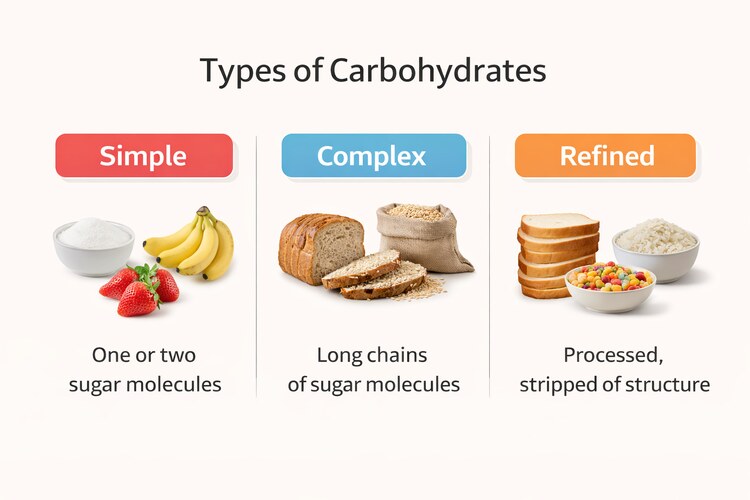

Carbohydrates are usually explained using neat categories: simple, complex, refined. You’re told that simple carbs spike blood sugar, complex carbs are slow and healthy, and refined carbs are the ones to avoid. On paper, it sounds like an easy system to follow.

In practice, it rarely works that way.

Many foods labeled as “complex” can raise blood sugar just as fast as sugar itself. Whole, unprocessed carbs can still keep the body running almost entirely on glucose. And swapping refined carbs for “healthier” ones doesn’t always fix energy crashes, hunger, or blood sugar issues — which leaves people wondering what they’re missing.

The problem is that carb labels describe what foods look like chemically, not what they do once you eat them.

This article breaks down what simple, complex, and refined carbohydrates actually are, how each behaves during digestion, and why their labels often fail to predict real metabolic effects. More importantly, it explains what matters more than carb type — so you can understand how carbohydrates influence blood sugar, fuel use, and energy in the real world, not just on a nutrition label.

What Are Simple Carbohydrates?

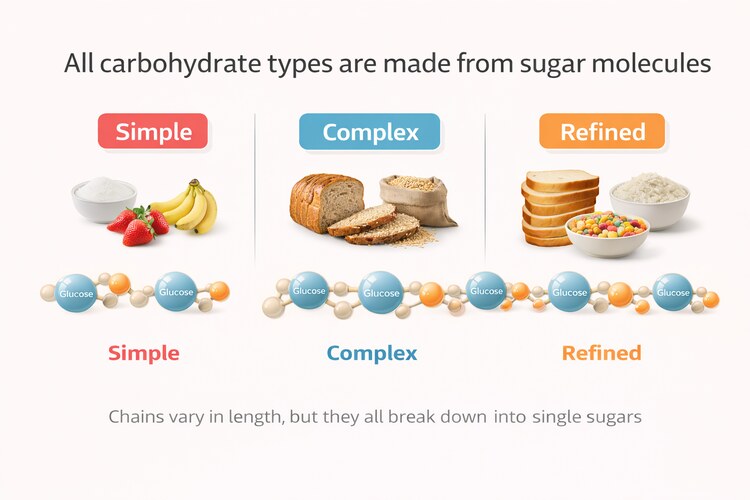

To understand simple carbohydrates, it helps to clear up one important point first: all carbohydrates are built from sugar molecules.

“Carbohydrate” is an umbrella term. Some carbs are made from a single sugar molecule, others from long chains of them — but they’re all constructed from the same basic units. Digestion is simply the process of breaking those chains back down into individual sugars.

For a more in depth look at exactly what carbs are, as well as common misconceptions, see this article here.

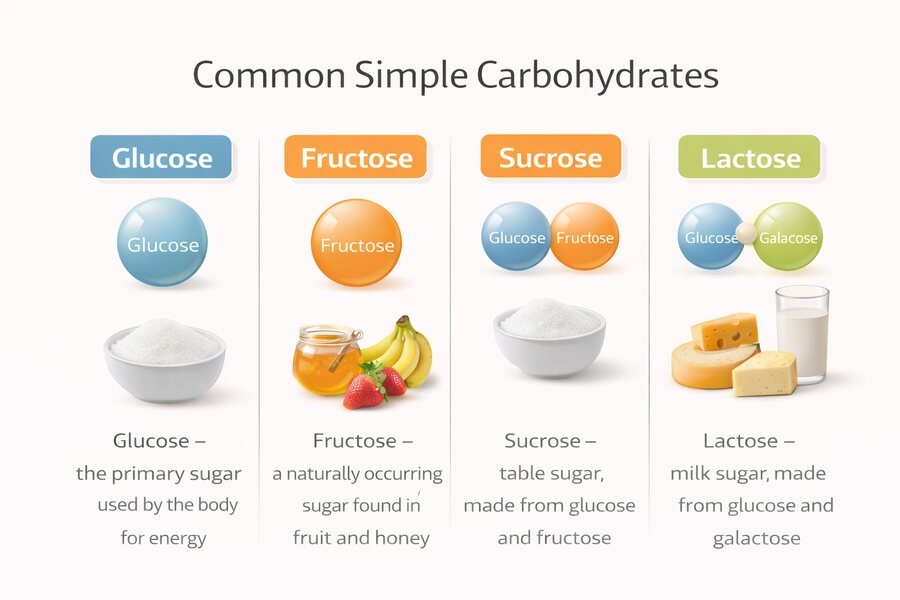

Simple carbohydrates are the smallest of these structures. They’re made up of one or two sugar molecules, which means the body has very little work to do before absorbing them into the bloodstream.

In practical terms, simple carbs become sugar very quickly.

The most common simple carbohydrates include:

- Glucose – the primary sugar used by the body for energy

- Fructose – a naturally occurring sugar found in fruit and honey

- Sucrose – table sugar, made from glucose and fructose

- Lactose – milk sugar, made from glucose and galactose

Because these sugars are already small and require minimal digestion, they tend to raise blood glucose rapidly and trigger a noticeable insulin response. This is why foods high in simple carbohydrates often produce quick energy followed by equally quick drops.

It’s important to note that simple does not automatically mean processed or unhealthy. Fruit contains simple sugars, but it also includes fiber, water, and micronutrients that slow absorption and change how those sugars affect the body.

The key takeaway is that simple carbohydrates describe molecular structure, not nutritional quality. Their impact depends on how much you eat, how often, and the metabolic context — not just the fact that they’re chemically simple.

What Are Complex Carbohydrates?

Complex carbohydrates are carbohydrates made from longer chains of sugar molecules, usually glucose. Instead of one or two sugars linked together, complex carbs contain dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of glucose units joined in a chain.

This is why they’re called complex — not because they behave differently once absorbed, but because their structure is larger and more intricate.

Common sources of complex carbohydrates include:

- Bread, rice, pasta, and grains

- Potatoes and other starchy vegetables

- Legumes such as beans and lentils

During digestion, these long chains are broken down step by step into individual glucose molecules. Once that process is complete, the end result in the bloodstream is the same as with simple carbs: glucose. The main difference is how quickly that glucose appears.

In theory, complex carbohydrates digest more slowly than simple sugars. In practice, the speed varies widely depending on processing, cooking, fiber content, and portion size. Finely milled flour, puffed grains, or well-cooked starches can raise blood sugar just as rapidly as sugar itself.

This is where much of the confusion comes from. The term complex is often used to imply “slow,” “stable,” or “healthy,” but complexity on paper doesn’t guarantee a gentle metabolic response.

Whole, intact foods tend to slow digestion somewhat, while refined or heavily processed versions behave much more like sugar. But in all cases, complex carbohydrates are still chains of sugar that ultimately become glucose.

So while complex carbohydrates may differ in how fast they’re digested, they are not a fundamentally different fuel. They’re the same building blocks — just assembled into longer chains.

What Are Refined Carbohydrates?

Refined carbohydrates are carbohydrates that have been processed to remove parts of the original food, usually fiber, fat, protein, and micronutrients. What remains is a concentrated source of starch or sugar that the body can digest very quickly.

Refining doesn’t change what carbohydrates are made of — they’re still chains of sugar molecules — but it changes how fast and how forcefully those sugars reach the bloodstream.

Common examples of refined carbohydrates include:

- White flour and foods made from it (bread, pastries, pasta)

- White rice

- Breakfast cereals

- Sugar and high-fructose corn syrup

- Many packaged and ultra-processed foods

In whole foods, carbohydrates are embedded within a complex physical structure: intact plant cells, fiber, water, and accompanying nutrients. Refining strips much of that structure away. Digestion becomes easier, faster, and more complete.

As a result, refined carbohydrates tend to raise blood glucose more rapidly, which triggers higher insulin responses while also providing less satiety per calorie.

This is why refined carbs often behave metabolically more like sugar than like whole foods — even when they’re technically “complex” carbohydrates. White bread, for example, is made from long chains of glucose, yet it can spike blood sugar as fast as, or faster than, table sugar.

It’s also why carb labels can be misleading. A food can be complex (long sugar chains), refined (structure removed), and fast-absorbing (high glucose impact), all at the same time.

The key point is that refining changes how carbohydrates act in the body, not what they become. Whether simple or complex, once refined, carbs tend to behave similarly: quickly delivering glucose and keeping the body in a glucose-dominant metabolic state.

Simple vs Complex vs Refined — The Real Differences

By this point, it should be clear why carbohydrate labels cause so much confusion. Simple, complex, and refined describe different characteristics of food, but they’re often treated as if they describe different metabolic outcomes. They don’t.

At the most basic level, all digestible carbohydrates end up in the same place: as glucose in the bloodstream. The differences between carb types lie in how quickly and how predictably that glucose appears — not in whether it appears at all.

Simple carbohydrates deliver glucose quickly because they’re already small sugar units. Complex carbohydrates deliver glucose slightly more slowly because they must be broken down first. Refined carbohydrates deliver glucose quickly because processing has removed the natural barriers that slow digestion. But in every case, the end product is the same.

This is why a food can be both complex and refined at the same time. White bread is made of long chains of glucose (complex), yet those chains are finely milled and rapidly absorbed (refined). Metabolically, it behaves far more like sugar than its “complex carb” label suggests.

To see exactly how the body reponds to any type of carbohydrate, see this article here.

What matters more than the category is the total glucose load, the speed of absorption, and the frequency of exposure. A small amount of carbohydrate eaten occasionally is very different from large amounts eaten repeatedly throughout the day, regardless of whether the source is labeled simple or complex.

Fiber and food structure can slow absorption and blunt blood sugar spikes, which is why whole foods generally behave better than processed ones. But slower does not mean neutral. Even whole-food carbohydrates still suppress fat burning and ketone production for as long as glucose and insulin remain elevated.

In other words, these classifications tell you something about food chemistry, but very little about long-term metabolic effects. They can be useful descriptors, but they don’t answer the question most people are actually asking: Will this keep my body in glucose-burning mode, or allow it to switch fuels?

Comparing Simple, Complex, and Refined Carbohydrates

| Category | Simple Carbs | Complex Carbs | Refined Carbs |

| Common perception | Often considered healthy when “natural” | Viewed as slow, stable, and safer | Widely seen as unhealthy |

| Typical examples | Fruit, honey, milk, table sugar | Rice, oats, potatoes, legumes | White bread, cereal, pastries, soda |

| Degree of processing | Low to moderate | Low to moderate (varies by preparation) | High |

| Digestion speed | Fast | Slower on average, but variable | Very fast |

| Blood sugar impact | Rapid glucose rise | Glucose rise still occurs | Sharp glucose spikes |

| Insulin response | Moderate to high | Moderate | High |

| Key metabolic reality | Quickly becomes glucose | Fully converted to glucose | Delivers glucose rapidly with low satiety |

How the Body Uses Different Fuel Systems

To understand why carbohydrate type matters less than it’s often made out to, it helps to understand how the body actually fuels itself.

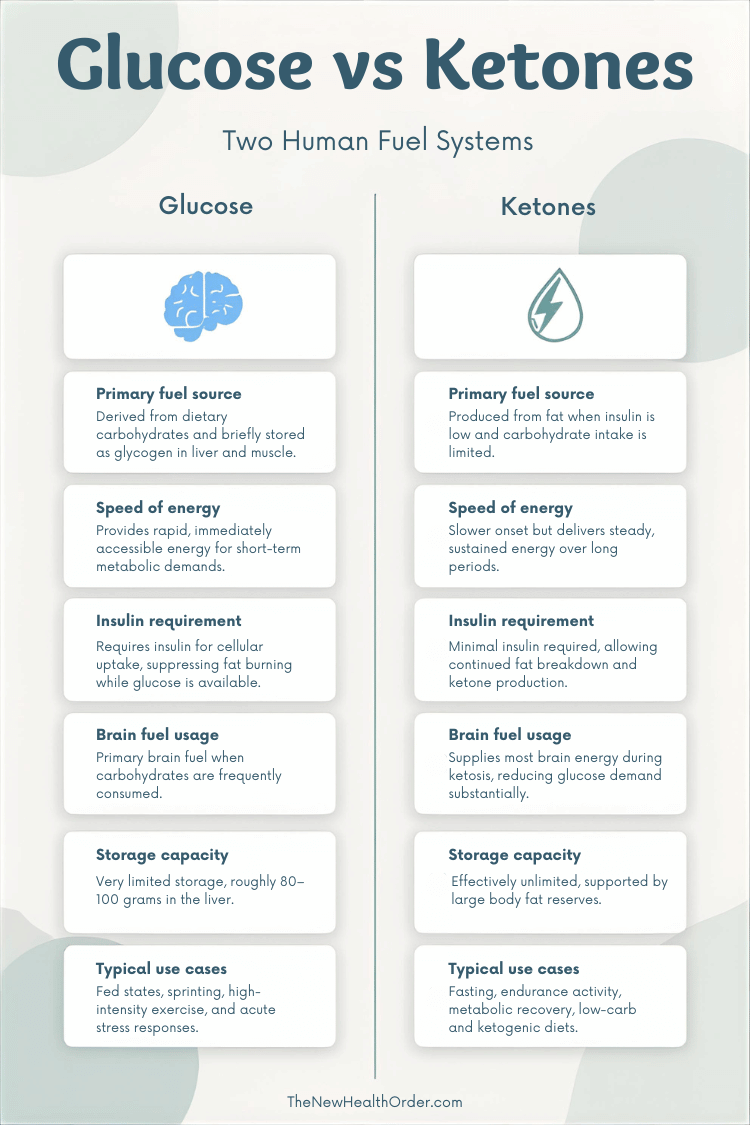

Humans are not designed to run on a single fuel. The body can operate primarily on glucose when carbohydrates are available, or shift toward fat and ketones when they are not. Both systems are normal, built-in parts of human metabolism.

For an in-depth look at the effect of carbs, protein, and fat on metabolism, see this article here.

When carbohydrates are eaten, glucose enters the bloodstream and insulin rises to manage it. As long as glucose is readily available, the body will preferentially use it for energy. This is efficient and useful for short-term demands.

See this article here for an in-depth look at insulin and why it’s fundamental to metabolic health.

When carbohydrate intake drops — or when enough time passes between meals — insulin levels fall. At that point, the body increases fat burning and produces ketones in the liver, which can supply energy to most tissues, including the brain. This fuel state is called ketosis.

Neither of these states is inherently good or bad. What matters is whether the body can move between them. This ability is often referred to as metabolic flexibility.

Modern diets tend to keep glucose constantly available, which means the fat- and ketone-based system is used less often — not because it’s unnecessary, but because it’s rarely required. In fact, considering it often takes over 24 hours to deplete the liver of glycogen, it is likely that the majority of the Western World have not produced ketones for years, and often decades.

Understanding this dual-fuel design makes it easier to evaluate carbohydrate advice without reducing it to “carbs good” or “carbs bad.”

For a more in depth look at ketones and the ketosis, see this article here.

What Actually Matters More Than Carb Type

Once you move past labels like simple, complex, and refined, a clearer picture starts to emerge. The body doesn’t respond to carbohydrate categories — it responds to glucose exposure, insulin signaling, and time.

Several factors matter far more than whether a carb is technically simple or complex.

Total glucose load

How much glucose enters the bloodstream matters more than its source. A large portion of “healthy” whole-food carbs can deliver more total glucose than a small amount of sugar — even if absorption is slightly slower. For example, a typical bowl of rice contains 45 g of glucose molecules, while a 12 oz can of soda delivers only 20 g of glucose.

Speed of absorption

Faster absorption leads to higher and sharper blood sugar spikes, which require larger insulin responses. Processing, grinding, cooking, and refining all accelerate absorption, regardless of carb type. Using the rice and soda example again: rice peaks insulin in around 45-90 minutes compared to soda’s 15-30 minutes.

Meal frequency

Eating carbohydrates frequently keeps glucose and insulin elevated throughout the day. Even moderate amounts can become problematic if the body is never given time to return to a low-insulin, fat-burning state.

Insulin sensitivity

Two people can eat the same carbohydrate and have completely different responses. Insulin-sensitive individuals clear glucose efficiently. Insulin-resistant individuals experience higher, longer-lasting blood sugar and insulin elevations.

Food structure and fiber

Fiber, intact cell walls, and water content can slow digestion and reduce peak glucose levels. This helps — but it doesn’t eliminate the underlying glucose load or its effects on fuel switching.

Time away from glucose dominance

Perhaps the most overlooked factor is whether the body ever spends meaningful time without incoming glucose. Fat burning, ketone production, and metabolic recovery only occur when insulin is low long enough for these systems to engage.

When viewed this way, carb type becomes secondary. What matters is not whether a carbohydrate is “simple” or “complex,” but whether its intake keeps the body locked in glucose-burning mode — or allows it to switch fuels.

This is the distinction most dietary advice misses. Carbohydrates aren’t just calories; they’re signals. And the signal they send depends less on the label and more on how often, how much, and in what metabolic context they’re consumed.

To explore exactly how many carbohyrates the body really needs per day, see this article here.

Simple vs Complex vs Refined: What They Actually Mean

| Carb Classification | What It Describes | How the Body Typically Responds |

| Simple carbs | One or two sugar molecules | Rapid glucose rise, quick insulin response |

| Complex carbs | Long chains of sugar molecules | Slower digestion, but still becomes glucose |

| Refined carbs | Processed, stripped of structure | Fast absorption, larger glucose spikes |

| Whole-food carbs | Intact plant structure and fiber | Same amount of glucose, but slower absorption and smaller glucose peaks |

Why “Healthy Carbs” Can Still Be A Problem

The idea of “healthy carbs” usually refers to whole, minimally processed foods like fruit, oats, brown rice, potatoes, and legumes. Compared to refined sugars and white flour, these foods often contain more fiber, micronutrients, and water — and that does matter.

But healthier does not mean metabolically neutral.

Even whole-food carbohydrates still break down into glucose. They still raise blood sugar. And they still trigger insulin. The difference is often one of degree, not kind.

Fruit juice, for example, the staple of a healthy breakfast, typically has only a slightly lower glycemic index (GI 45-53) and sugar content (30-36g per 12 oz) compared to soda (~39g sugar, GI ~63). Both deliver a rapid load of liquid simple sugars that trigger similarly strong blood sugar and insulin spikes—making fruit juice not substantially better than soda for insulin responsiveness when consumed in typical amounts.

Fiber and intact food structure can slow absorption and reduce glucose spikes. This is why eating fruit is much better than drinking its juiced form. But they don’t change the destination.

As long as glucose is entering the bloodstream, insulin remains active and fat burning remains suppressed. For someone already eating carbohydrates frequently, swapping refined carbs for “healthy” ones may improve nutrient intake — but it doesn’t necessarily restore metabolic flexibility.

This is where many people get stuck. They clean up their food choices, avoid sugar, choose whole grains, and still struggle with energy swings, hunger, or fat loss. The issue isn’t the quality of the carbs — it’s the constant presence of glucose.

Another overlooked factor is quantity. Whole foods are often easier to overconsume than expected. A large bowl of rice, oats, or fruit can deliver a substantial glucose load without tasting sweet or feeling indulgent. From a metabolic standpoint, the body still has to manage that influx.

“Healthy carbs” can absolutely be part of a diet — especially in active, insulin-sensitive individuals or specific performance contexts. The problem arises when they’re treated as required or unlimited, rather than as a tool with trade-offs.

Unfortunately, healthy carbs are still carbs. They may be slower, gentler, and more nutrient-dense, but if they prevent the body from ever leaving glucose-dominant metabolism, they can still contribute to long-term metabolic strain.

When Carb Type Actually Does Matter

Although carb labels are often overemphasized, there are situations where the type of carbohydrate consumed can make a meaningful difference.

One clear example is high-intensity physical performance. Short, explosive efforts — sprinting, interval training, competitive sports — rely heavily on glucose. In these contexts, faster-digesting carbohydrates can improve performance, delay fatigue, and support recovery between efforts. Here, refined or simple carbs may be used strategically rather than habitually.

Carb type can also matter during targeted refeeding after prolonged low-carb intake, fasting, or intense training. In these cases, certain carbohydrates may replenish glycogen more efficiently with fewer digestive issues. This is about timing and purpose, not daily reliance.

Another situation is digestive tolerance. Some people tolerate certain carb sources better than others due to gut sensitivity, microbiome differences, or food intolerances. In these cases, choosing between fiber-rich or lower-fiber carb sources can affect comfort and adherence, even if the metabolic end result is similar.

Outside of these narrower contexts, carb type tends to matter far less than most advice suggests. For sedentary or moderately active individuals eating carbohydrates throughout the day, switching from refined to whole-food carbs may improve nutrient intake — but it rarely changes the underlying metabolic state.

This is the key distinction: carb type matters most when carbs are used intentionally. When they’re consumed by default, in large amounts, or at every meal, their chemical classification becomes secondary to the fact that glucose is always present.

Understanding when carb type matters — and when it doesn’t — helps shift carbohydrates from a rule-based staple into a strategic tool.

Final Thoughts: What Actually Matters

By now, it should be clear that carbohydrate classifications explain structure, not outcome.

Simple, complex, and refined carbohydrates differ in how they’re built and how quickly they’re digested — but once digestion is complete, the body is dealing with the same thing: glucose. The metabolic impact depends far more on how much glucose enters the bloodstream, how often it happens, and whether the body is ever given time to switch fuels.

This doesn’t mean carbohydrate type is irrelevant. It means it’s secondary. Labels can provide context, but they don’t override total intake, absorption speed, meal timing, or individual insulin sensitivity.

Understanding this distinction helps move carbohydrate decisions out of rigid rules and into practical strategy. Instead of asking whether a carb is simple, complex, or refined, the more useful question becomes: How does this fit into my overall metabolic picture?

When carbs are used intentionally, their type can matter. When they’re consumed by default, the label rarely makes the difference people expect.

FAQs

Are complex carbs healthier than simple carbs?

Complex carbs digest more slowly, but they still become glucose. Slower absorption doesn’t mean a lower total glucose load or different fuel outcome.

Are refined carbs worse than all other carbs?

Refined carbs raise blood sugar faster, but large amounts of whole-food carbs can produce similar metabolic effects if eaten frequently.

Do simple carbs always spike blood sugar?

Simple carbs raise blood sugar quickly, but fiber, food structure, and portion size can modify how strong and rapid the spike is.