Ketones are often talked about as if they’re either a breakthrough or a danger — a metabolic superpower for some, and a red flag for others. In reality, what they mean depends entirely on context. Ketones are a normal part of human metabolism, and misunderstanding them has led to unnecessary confusion about diet, fat loss, performance, and metabolic health.

This article isn’t about promoting ketosis or warning you away from it. It’s about understanding what ketones actually are, why the body makes them, when they appear, and how they’re used — without diet ideology, fear-based framing, or oversimplified rules. By the end, you’ll be able to interpret ketones in context, understand what they do (and don’t) say about fat burning and health, and see how they fit into a larger, more flexible view of metabolism.

If you’ve ever wondered whether ketones matter for you, why people respond to them so differently, or how they relate to insulin, glucose, and long-term metabolic resilience, this article will give you the framework to make sense of it — and the confidence to keep learning without chasing numbers or trends.

What are Ketones?

Ketones, and ketosis more generally, tend to attract strong opinions on both sides, but most of that confusion comes from a lack of clear definitions. Before talking about when ketones appear or what they might mean for health, it helps to understand what they actually are and what role they play in normal human metabolism.

Ketones Are a Normal Part of Energy Metabolism

Ketones are commonly described as a backup or emergency fuel — something the body turns to only during starvation or extreme deprivation. In that framing, ketones are tolerated rather than valued, and the assumption is that a healthy metabolism should rarely need them. This view is intuitive, but incomplete.

A metabolism that rarely accesses ketone-based fuel and remains locked in a glucose-only mode is not inherently more efficient or safer over the long term. In fact, this kind of rigid glucose dependence is commonly seen alongside the early stages of metabolic dysfunction, particularly as activity levels decline and insulin sensitivity worsens with age. The core issue is adaptability. When glucose handling is no longer effortless, a metabolism with fewer available fuel pathways becomes increasingly constrained.

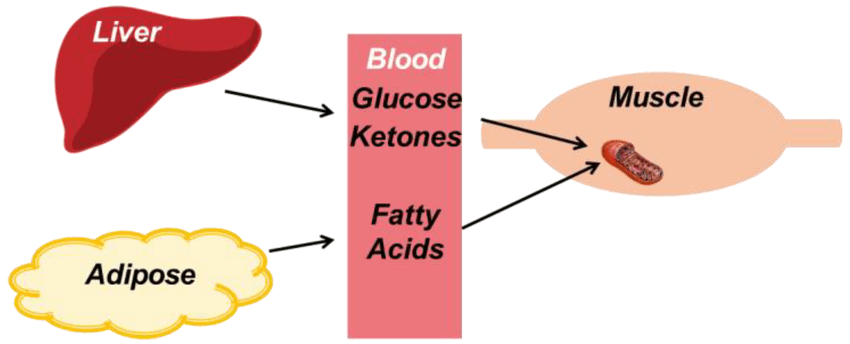

At a basic level, ketones are small, water-soluble molecules the body uses to produce energy. They are made in the liver and released into the bloodstream, where they can be taken up by tissues and converted into usable fuel. Like glucose and fatty acids, ketones are a normal energy substrate — one of several ways the body keeps cells powered under different conditions. Their presence does not signal failure or emergency; it reflects a shift in how energy is sourced and distributed.

The body produces three ketone bodies: acetoacetate, beta-hydroxybutyrate, and acetone. Beta-hydroxybutyrate is the most abundant in circulation and the one most commonly measured, which is why it tends to dominate discussions about ketosis. But ketones do not operate in isolation. They function as a coordinated system regulated by hormonal signals and energy demand, not as a single molecule acting independently.

The concern arises when this system becomes inaccessible. In the United States, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggest that nearly one in three adults are already prediabetic, with many more showing signs of insulin resistance despite feeling generally healthy. In this earlier stage, blood glucose may still appear normal, but it is maintained by chronically elevated insulin.

Persistently high insulin keeps fat locked away and suppresses ketone production. Over time, this leaves the body with fewer usable fuel options and an increasing dependence on glucose to meet everyday energy needs. The problem is timing: this dependence deepens just as glucose regulation is beginning to strain. Suppressed ketones matter not because they are “better” than glucose, but because losing access to them removes the body’s ability to shift fuels when glucose is no longer handled smoothly.

For many people, this narrowed fuel strategy can persist for years before it is labeled as prediabetes or diabetes. Blood sugar may only rise later, but the underlying issue shows up earlier: a metabolism that has fewer ways to respond to fasting, missed meals, illness, or declining activity. By the time a diagnosis appears, the challenge is not simply elevated glucose, but a system that has already lost flexibility.

Ketones are part of what prevents this narrowing. While they do rise during fasting or prolonged periods without food, they are not an emergency signal. Their production reflects a normal, regulated response that allows energy to keep flowing when glucose alone is no longer sufficient or reliable.

Where Ketones Come From — and What They Actually Do

Ketones are made in the liver from fat, but not because the body is trying to burn fat faster or more aggressively. Fatty acids are highly energy-dense, yet they are relatively difficult to transport, and some tissues cannot use them directly. The brain, in particular, is protected by the blood–brain barrier and cannot rely on fatty acids as a primary fuel source.

Ketones solve this logistical problem. By converting fat-derived energy into small, water-soluble molecules, the liver creates a form of fuel that circulates easily through the bloodstream and can reach tissues that fat alone cannot. In this sense, ketones are not just another fuel — they are a delivery system that allows fat-based energy to be distributed where it is needed most.

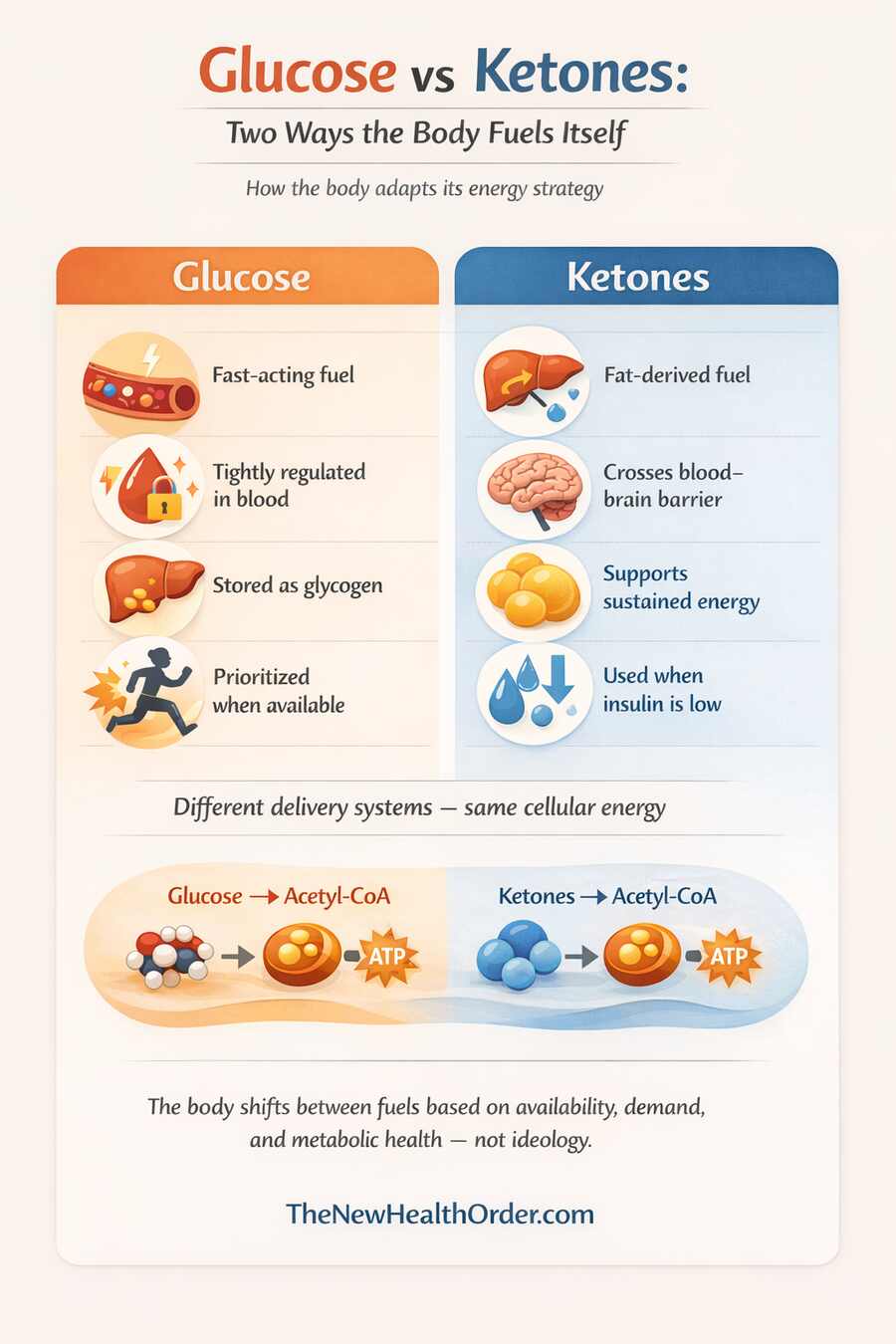

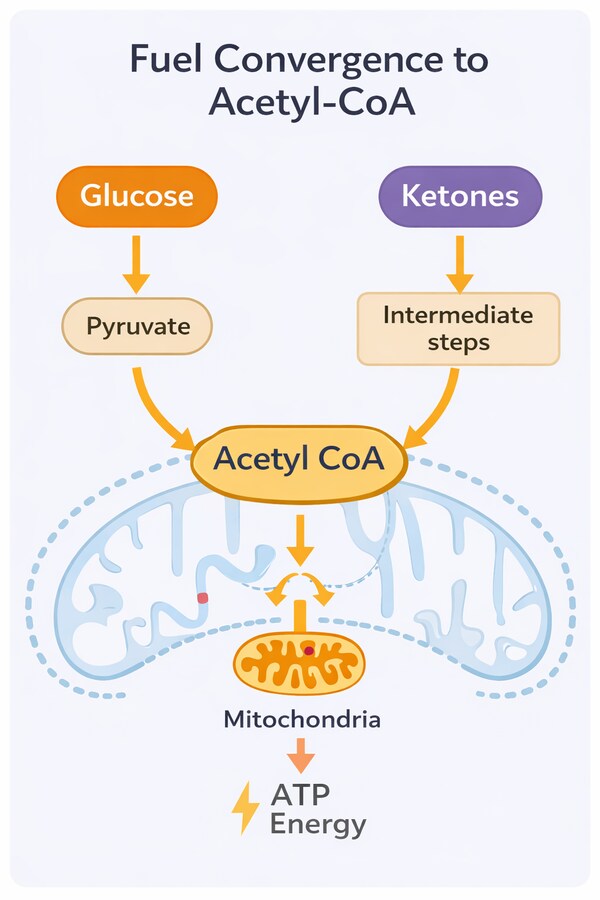

At the cellular level, both glucose and ketones ultimately produce the same end product: acetyl-CoA, the molecule that enters the Krebs cycle to generate ATP (the form of energy cells use).

The difference between glucose and ketones is not the energy they provide, but how that energy is packaged, transported, and delivered to the intended destination. Ketones allow energy derived from fat to reach glucose-dependent tissues when glucose availability is reduced.

For this reason, it is misleading to think of ketones purely as a last-resort fuel. Their presence reflects a broader metabolic state involving changes in hormone signaling and fuel partitioning — a shift we’ll explore in more detail in the next section, where we look at why the body makes ketones in the first place.

Ketones exist because the body needs a reliable way to supply energy when glucose availability changes. They are not a signal that the body is starving or in trouble, but a normal response to conditions where relying exclusively on glucose would be inefficient or unnecessary. Ketone production reflects a shift in fuel strategy, not a metabolic failure.

In fact, the shift into ketosis does more than change how fuel is delivered. When ketones become a meaningful energy source, the body also enters a state that favors cellular repair, metabolic housekeeping, and reduced growth signaling. Processes involved in cellular cleanup and stress resistance become more active, while constant fuel storage and turnover slow down. These effects are not unique to ketosis alone, but they are closely associated with the metabolic state in which ketones dominate. If you want to explore these effects in more detail, including what they may mean for long-term health, they’re covered more fully in our article on the benefits of the ketogenic diet.

The Energy Problem Ketones Solve

Glucose is the body’s most familiar fuel and is the form of energy derived from most carbohydrate-based foods. It circulates in the blood and can be rapidly used by many tissues, which makes it well suited for immediate energy needs. However, glucose must be maintained within a narrow range, it is stored only in limited amounts as glycogen, and it depends heavily on regular dietary intake.

Fat represents a far larger energy reserve, but it cannot always be used directly. Fatty acids are difficult to transport and cannot cross certain protective barriers, including the blood–brain barrier. This creates a practical problem: the body may have ample stored energy, yet limited access to it in tissues that depend on a continuous fuel supply.

Ketones solve this problem by converting fat-derived energy into a form that can circulate easily through the bloodstream and reach glucose-dependent tissues. In doing so, they allow the body to maintain energy availability without constant reliance on carbohydrate intake. Rather than replacing glucose entirely, ketones complement it, ensuring that energy delivery remains stable across a wide range of conditions.

Ketones as a Backup — Not an Emergency

Ketones are often described as a backup fuel, and in one sense that description is accurate — they tend to rise when glucose availability is reduced. But a backup system does not imply distress. It implies redundancy. Ketone production does not signal starvation or metabolic danger; it signals that the body has shifted to a different, equally regulated way of meeting its energy needs.

This distinction matters because it reframes ketosis as a controlled and purposeful state rather than a sign of deprivation. Ketones rise in contexts where insulin levels are low and stable, allowing fat-derived energy to be mobilized and distributed efficiently. The body does not enter this state by accident, nor does it lose control when ketones appear.

Understanding ketones as a regulated backup rather than an emergency response helps explain why they have always been part of human metabolism, and why they are commonly misunderstood today.

When Ketones Are Produced

Ketones don’t appear because of one specific food or diet label. They show up when the body shifts how it fuels itself, based on hormones and how much energy is actually available. To understand when ketones are produced, it helps to stop thinking in terms of diets and start thinking about what signals the body is responding to.

Low Insulin Is the Primary Trigger

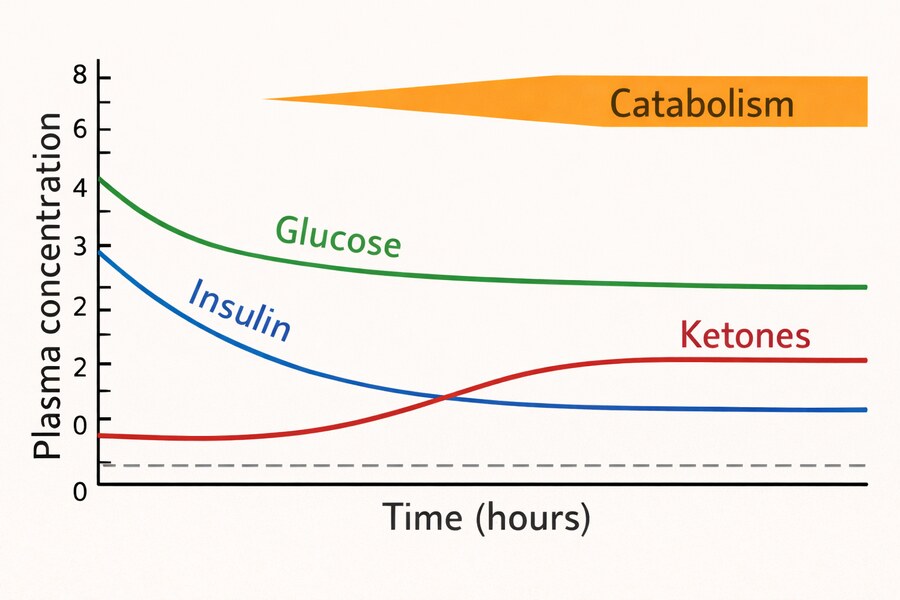

The most important signal for ketone production is low insulin. Insulin is a hugely influential and powerful gatekeeper hormone, directing whether the body prioritizes storing energy or releasing it for use. When insulin levels are elevated, fat breakdown is suppressed and ketone production remains minimal. When insulin falls, stored fat becomes accessible, and the liver begins converting fatty acids into ketones.

This is why ketones are commonly associated with fasting, longer gaps between meals, and periods of reduced carbohydrate intake. In these situations, insulin levels decline not because the body is in distress, but because immediate glucose handling is no longer the dominant priority. Lower insulin allows fat-derived energy to circulate and signals that an alternative fuel pathway can be engaged.

Importantly, this process is gradual rather than binary. Insulin does not need to drop to zero for ketones to appear, and small amounts of insulin remain present even during nutritional ketosis. Ketone production rises and falls along a continuum, reflecting the balance between insulin signaling and energy demand rather than an on–off switch.

Glycogen Depletion and Fat Flux

Glycogen, the stored form of glucose in the liver and muscles, plays a key supporting role in ketone production. Liver glycogen in particular acts as a short-term buffer, helping maintain blood glucose between meals. Once liver glycogen becomes depleted (the liver stores roughly 80–100 g of glycogen—enough to maintain blood glucose for about 12–24 hours before other fuels are needed), the body must rely more heavily on other energy sources to meet ongoing demand.

As glycogen availability falls, falling insulin and rising glucagon signal that stored energy should be released, causing fatty acids to be released from fat tissue and delivered to the liver in greater amounts — a process often described as increased fat flux. When the supply of fatty acids exceeds the liver’s immediate energy needs, the excess is diverted into ketone production. This is not a wasteful process, but an efficient way to package and distribute energy derived from fat.

It’s also important to recognize that glycogen depletion does not require extreme deprivation. Overnight fasting, prolonged gaps between meals, illness, extended periods of low activity followed by exertion, and sustained energy demand can all reduce liver glycogen enough to promote ketone production. A metabolically healthy person should produce some ketones every night, even eating carbs throughout the day. In this sense, ketones are a normal response to changing energy conditions, not a marker of starvation.

That said, the timeline for ketone production varies widely between individuals. Some people may produce small amounts of ketones overnight, while others may not produce measurable ketones for days or even weeks, despite making genuine metabolic improvements. Factors such as insulin resistance, habitual carbohydrate intake, activity level, and overall metabolic health all influence how quickly this shift occurs. For this reason, the presence or absence of ketones at any given moment should always be interpreted in context, rather than treated as a verdict on progress or success.

How Ketones Are Used for Energy

Once ketones are produced and released into the bloodstream, they’re taken up by tissues and used for energy. At this point, it’s easy to fall into a common trap: focusing too closely on blood ketone numbers as if higher always means better. In reality, what matters far more is which tissues are using those ketones and under what conditions. Ketones aren’t a universal fuel that every cell suddenly prefers, and blood levels on their own don’t tell you whether they’re being used efficiently or supporting good metabolic health. Ketone measurements can be useful, but only when they’re viewed alongside other signals, not treated as a standalone metric.

Ketones and the Brain

The brain is one of the main reasons ketones exist at all. Under normal conditions, it relies heavily on glucose for energy, but it can’t store much of it and it can’t use fatty acids directly. That limitation is enforced by the blood–brain barrier, which protects the brain but also restricts its fuel options.

This is where the familiar claim that the brain “needs” about 130 grams of glucose per day comes from. That number was based on measurements in glucose-dependent individuals and later adopted by the Institute of Medicine as a reference intake. Even then, the authors were clear that this glucose doesn’t have to come from dietary carbohydrates — only that the brain requires access to glucose when glucose is the primary fuel.

What often gets left out is that this requirement isn’t fixed. When ketones are available, the brain uses them readily, and its glucose needs drop substantially. In fasting or ketone-adapted states, studies show the brain may use closer to 40–44 grams of glucose per day, with ketones supplying much of the rest. Glucose doesn’t disappear, but it stops doing all the work.

Ketones cross the blood–brain barrier easily, which makes them a reliable way to keep the brain fueled when glucose intake falls or glycogen runs low. This helps stabilize brain energy without pushing blood sugar to extremes. It’s not an on–off switch, but a shared workload: glucose and ketones are used together, with their roles shifting based on availability and metabolic context.

Ketones and Muscle Tissue

Skeletal muscle is much more flexible than the brain when it comes to fuel. It can run on glucose, fat, or ketones, and it constantly shifts between them based on what’s available and how hard it’s working. During low to moderate effort — walking, working, steady exercise — muscle tends to rely mostly on fat, especially in people who are used to burning it efficiently. Fat is slow-burning and plentiful, which makes it ideal for sustained activity.

Muscles can use ketones too, particularly when they’re circulating in higher amounts. But as muscle becomes better at accessing fat directly, it often doesn’t need to rely on ketones as much. Instead of “preferring” ketones, muscle uses them when it makes sense and bypasses them when it doesn’t, depending on the situation.

That’s why blood ketone numbers can be misleading. Seeing higher ketones doesn’t automatically mean your muscles are burning more fat or running on ketones as their main fuel. In fact, in many trained or metabolically adapted people, muscles may use mostly fatty acids and leave ketones available for tissues that need them more.

The Heart and Other High-Energy Organs

The heart is one of the most metabolically flexible organs in the body. It operates continuously, with extremely high energy demands, and it readily uses whatever fuel is most efficient and available at the time. Under normal conditions, the heart relies heavily on fatty acids, but it can also use glucose, lactate, and ketones as and when it needs.

When ketones are present, the heart readily takes them up and oxidizes them for energy. From a metabolic standpoint, ketones are an efficient oxidative fuel, providing a high yield of energy relative to the oxygen required to metabolize them. This efficiency helps explain why ketone use increases in tissues with constant and demanding energy needs, such as the heart and brain.

Other high-energy organs, including the kidneys and parts of the gut, also utilize ketones to varying degrees depending on metabolic state. As with the brain and muscle, ketones do not replace other fuels entirely. Instead, they expand the range of usable energy sources, allowing these tissues to maintain function across changing conditions.

Fuels by tissue

| Tissue / Organ | Glucose Use | Fatty Acid Use | Ketone Use | Notes |

| Brain | High (baseline) | None | High (when available) | Ketones reduce, but never eliminate, glucose needs |

| Skeletal muscle (rest / low intensity) | Low–moderate | High | Low–moderate | Prefers fatty acids when demand is steady |

| Skeletal muscle (high intensity) | High | Low | Minimal | Rapid ATP demand favors glucose |

| Heart | Moderate | High | High | Extremely flexible; readily uses ketones |

| Liver | Some (self-use) | High (oxidation) | Produces ketones | Does not use ketones it produces |

| Adipose tissue | Minimal | Stores/releases fat | None | Highly insulin-sensitive |

| Kidneys | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Can use ketones, especially during fasting |

| Red blood cells | 100% | None | None | No mitochondria; glucose only |

Ketones in the Blood vs Ketones Being Used

One of the most common sources of confusion around ketones comes from assuming that blood ketone levels directly reflect what the body is doing with fat. They don’t. Blood ketones tell you that ketones are present in circulation, but they say far less about how much fat is being burned or how effectively ketones are being used by tissues. Understanding this distinction is essential for interpreting ketone measurements correctly, and is where a lot of low-carb dieters get misled early on in their journey to better metabolic health.

High Ketone Levels Don’t Automatically Mean Fat Loss

Ketones appear in the blood when production exceeds immediate use. That point is often overlooked. Elevated blood ketones do not necessarily mean that the body is burning more fat than they would normally be, losing weight, or operating more efficiently. They simply indicate that ketones are being made faster than they are being consumed.

Fat loss depends on overall energy balance and fat mobilization over time, not on how many ketones happen to be circulating at a given moment. It is entirely possible to have high blood ketones while burning very little body fat, just as it is possible to burn substantial amounts of fat without seeing high ketone readings.

This comes down to supply and demand. Ketone production represents supply; tissue uptake and oxidation represent demand. When supply outpaces demand, ketones accumulate in the bloodstream. When demand rises — for example, as tissues become better adapted to using ketones — blood levels may actually fall, even though fat-derived energy use has increased. It’s a bit like fuel sitting in the tank — seeing more of it doesn’t tell you how fast the engine is actually running.

This is why chasing higher ketone numbers can be misleading. In many cases, lower or modest ketone levels reflect more efficient utilization, not metabolic failure.

Why Ketones Can Accumulate in the Blood

There are several reasons ketones may rise in the bloodstream, and not all of them reflect improved metabolic health or increased fat loss.

One reason is reduced ketone use. If tissues are not yet efficient at oxidizing ketones — which is common early in metabolic adaptation — ketones may build up simply because they are not being consumed quickly. As adaptation improves, blood ketone levels often decline despite continued ketone production, simply because the body is becoming more efficient at using them.

Another reason is increased ketone production. This can occur when insulin levels are very low, fatty acid delivery to the liver is high, or dietary intake is reduced. In these situations, the liver may produce ketones at a rate that temporarily exceeds tissue demand, leading to higher circulating levels.

Ketones can also accumulate during illness, physiological stress, or periods of very low food intake. In these contexts, elevated ketones reflect changes in energy availability and hormone signaling rather than intentional fat loss or metabolic optimization. This is another reason blood ketone readings should always be interpreted alongside broader context, including diet, activity level, health status, and overall energy intake.

The key takeaway is that blood ketones are more a snapshot of circulation, not necessarily a sign of success in themselves without a greater context. They reflect balance (or imbalance) between production and use.

Ketosis vs Ketoacidosis

Ketosis and ketoacidosis are often mentioned in the same breath, but they are fundamentally different states. Confusing the two has created unnecessary fear around ketones and has led many people to assume that any rise in ketones is dangerous. In reality, the distinction between them comes down to regulation — specifically, the presence or absence of insulin.

Nutritional Ketosis Is a Regulated State

Nutritional ketosis occurs when ketones rise in response to lower insulin levels, not the absence of insulin. Even in ketosis, insulin remains present and continues to regulate energy release, ketone production, and blood glucose. This hormonal control keeps ketone levels within a narrow physiological range and prevents them from rising unchecked.

Because insulin is still functioning, nutritional ketosis remains stable and self-limiting. The body adjusts ketone production based on demand, and tissues increase their ability to use ketones over time. This is why nutritional ketosis can occur during fasting, carbohydrate restriction, or prolonged energy demand without compromising safety in otherwise healthy individuals.

Ketoacidosis Is a Pathological Failure

Ketoacidosis is a medical emergency that occurs when insulin is absent or nearly absent, most commonly in people with untreated or poorly managed type 1 diabetes. Without insulin, ketone production is no longer regulated, blood glucose rises dramatically, and ketones accumulate to dangerous levels, leading to severe acid–base imbalance.

This is not a state that healthy individuals “slip into” through diet or fasting. As long as insulin is present and functioning, the body retains control over ketone production. Ketoacidosis reflects a breakdown of metabolic regulation, not an extension of nutritional ketosis.

Understanding this distinction is important. Ketosis is a controlled metabolic state that reflects fuel adaptation, while ketoacidosis is a loss of control driven by insulin failure. Conflating the two obscures both the safety of normal ketone production and the seriousness of true ketoacidosis.

Are Ketones “Better” Than Glucose?

This common question regarding ketones and glucose as competing fuels misses how the body actually uses energy, and therefore misses the greater point of metabolic health.

The question is not whether one fuel is superior in all circumstances, but how different fuels are prioritized, combined, and deployed depending on demand. Both glucose and ketones can support high levels of performance and normal physiology. The differences lie in speed, context, and constraint, not in inherent quality.

Different Fuels for Different Contexts

Glucose has one feature that sets it apart from other fuels: it has to be tightly controlled in the bloodstream. When blood sugar rises, the body must deal with it immediately, either by using it right away or storing it as glycogen. That’s why glucose is often burned first when it’s available. It isn’t always the most efficient fuel, but it is the most urgent one.

This urgency matters most during repeated, high-intensity efforts — sprinting, rapid changes of direction, or closely spaced near-maximal lifts. These efforts depend on very rapid ATP production through glycolysis, which fat and ketone metabolism cannot match for speed. Classic muscle studies showed that as exercise intensity rises, glycogen use increases dramatically, with glycogen depletion occurring 2–7× faster at workloads above ~60–80% of maximal aerobic capacity, and even more rapidly during supramaximal efforts.

What’s equally important is what happens when glycogen becomes limited. In controlled experiments by Bangsbo et al., peak power during a single maximal effort was not improved by starting with very high glycogen stores. However, when the same maximal effort was repeated after partial glycogen depletion, time to exhaustion fell, energetic stress markers rose, and performance broke down sooner — especially when muscle glycogen dropped below critical levels. In other words, glycogen didn’t raise maximal output, but it strongly influenced the ability to repeat maximal efforts without rapid fatigue.

Similarly, in endurance exercise and sustained resistance training, research shows that once keto-adaptation has occurred, performance is largely preserved. In one of the earliest controlled studies, Phinney and colleagues found that after several weeks in nutritional ketosis, participants maintained their ability to perform prolonged exercise despite consuming very little carbohydrate. More recent work, including the FASTER study, reinforced this finding in trained endurance athletes, showing no loss of aerobic capacity or endurance performance after long-term adaptation.

What changed was not performance, but fuel use. In the FASTER study, keto-adapted athletes burned fat at rates exceeding 2 grams per minute, roughly double that of high-carbohydrate athletes, while maintaining access to muscle glycogen when intensity increased. Muscles relied more heavily on fatty acids during steady output, ketones contributed where appropriate, and glucose was effectively conserved for moments when demand rose.

In real-world terms, the performance advantage of carbohydrates applies to a relatively small subset of the population engaging in very specific activities. It does not imply that glucose is universally superior, nor that ketones are limiting under most conditions.

Metabolic Flexibility Matters More Than Fuel Choice

The body doesn’t jump straight from running on blood sugar to running on fat and ketones. There’s a sequence. When glucose from a recent meal isn’t available, the first fallback is liver glycogen — stored glucose that can be released quickly to keep blood sugar steady. It’s fast, efficient, and that’s why the body uses it first.

For a deeper walkthrough of this sequence — including how the body prioritizes glucose, glycogen, fat, and ketones — we break it down step by step in our article on the body’s fuel hierarchy.

Only as those glycogen stores run down does the body lean more heavily on fat and ketones to keep energy flowing. That order isn’t about preference or diet style — it’s about efficiency. Glycogen is easy to access in the short term; fat-based fuels are better suited for going the distance. A healthy metabolism moves through these stages smoothly, without strain or disruption.

This is where metabolic flexibility really matters. A flexible system can handle glucose when it’s there, tap into glycogen when needed, and shift toward fat and ketones as conditions change. Ketones aren’t a replacement for glucose, and they aren’t meant to be a permanent destination. They’re part of a layered system that keeps energy available without requiring constant carbohydrate intake.

Problems arise when this flexibility is lost. Being stuck in one fuel mode — especially a glucose-only one — makes the system fragile. Energy regulation becomes harder, recovery suffers, and metabolic health slowly degrades. Ketones matter not because they’re “better” than glucose, but because the ability to produce and use them reflects a metabolism that can adapt.

The Bigger Picture

By this point, ketones should no longer feel mysterious, extreme, or ideological. They are not a diet trend to adopt or avoid, and they are not a metabolic state to chase. They are a normal part of human energy metabolism — one that becomes relevant when the body needs flexibility rather than constant dependence on a single fuel.

The most important takeaway is not whether ketones are “good” or “bad,” or whether you personally produce a certain amount of them. It’s understanding why they exist at all. Ketones solve a real biological problem: how to keep energy flowing when glucose availability changes, without compromising the function of vital organs. Seeing them in this light replaces fear and hype with clarity.

This understanding also changes how you interpret signals from your own body. Blood glucose, glycogen, fatty acids, and ketones are not competing forces — they are parts of a coordinated system. The body prioritizes clearing glucose when it is present, draws on glycogen when needed, and turns to fat and ketones as conditions shift. None of these steps are failures. They are expressions of adaptability.

For many people, especially those dealing with insulin resistance or long-standing metabolic dysfunction, this context matters deeply. Progress is not always visible through a single number or test. The absence of ketones at one moment does not mean nothing is improving, just as their presence does not guarantee success. What matters is whether the system as a whole is becoming more resilient and responsive over time.

Ultimately, understanding ketones is less about choosing a fuel and more about developing metabolic literacy. It’s learning how the body adapts, why rigid rules often fail, and why flexibility is a better long-term goal than control. This perspective doesn’t tell you what to eat or how to live — it gives you a framework for making sense of metabolic signals as your circumstances, activity levels, and health change.

If this article has done its job, it hasn’t given you answers to memorize. It’s given you better questions to ask. From here, exploring concepts like metabolic flexibility, insulin resistance, and fat storage becomes far more productive — not as isolated problems to fix, but as parts of an interconnected system designed to adapt.

That understanding is where meaningful, sustainable metabolic health begins.

FAQs

What exactly are ketones, and why does the body make them?

Ketones are water-soluble molecules made in the liver from fat when insulin is low. They allow fat-derived energy to reach tissues—like the brain—that can’t use fatty acids directly.

Does having higher ketones mean you’re burning more fat?

Not necessarily. High blood ketones reflect production, not usage. Efficient tissues may use ketones quickly, resulting in lower readings despite substantial fat-derived energy use.

Is ketosis safe, or is it the same as ketoacidosis?

Nutritional ketosis is a controlled, insulin-regulated state seen in fasting or low-carb intake. Ketoacidosis occurs only when insulin is absent, typically in uncontrolled diabetes.