Most nutrition debates frame metabolism as a choice: glucose or fat, carbs or keto, fed or fasted. That framing misses something more fundamental.

The body does not choose fuels based on preference or ideology. It follows a hierarchy — a structured, rule-based system that determines which fuel is used, when, and why. Understanding that hierarchy explains far more than any single diet ever could.

When you understand how the body prioritizes glucose, glycogen, fat, and ketones, a lot of confusion falls away. Fat storage stops looking like failure. Ketones stop looking extreme. Insulin stops looking like an enemy. And chronic metabolic issues start to look less mysterious.

This article will walk you through that hierarchy step by step — not to tell you what to eat, but to show you how the system actually works. You’ll learn why the body is designed to switch fuels, why modern life often prevents that from happening, and why metabolic health depends less on choosing the “right” fuel and more on restoring the ability to change gears.

If you’ve ever wondered why so many health debates feel contradictory, or why doing “everything right” still doesn’t feel right, this framework will make the rest of metabolism finally make sense.

What follows is not another diet argument — it’s the operating logic underneath all of them.

The Body’s Fuel Hierarchy: Glucose vs. Fat

When people ask whether the body prefers glucose or fat as fuel, they are usually asking the wrong question.

The body does not choose fuels based on preference or availability alone. It follows a fuel hierarchy designed to solve a specific physiological problem: keeping blood glucose within a narrow, safe range while ensuring a continuous supply of energy.

This may sound technical and unremarkable, but this constraint governs how energy is managed in the body, and much of what we call metabolic health — and dysfunction — follows downstream from it.

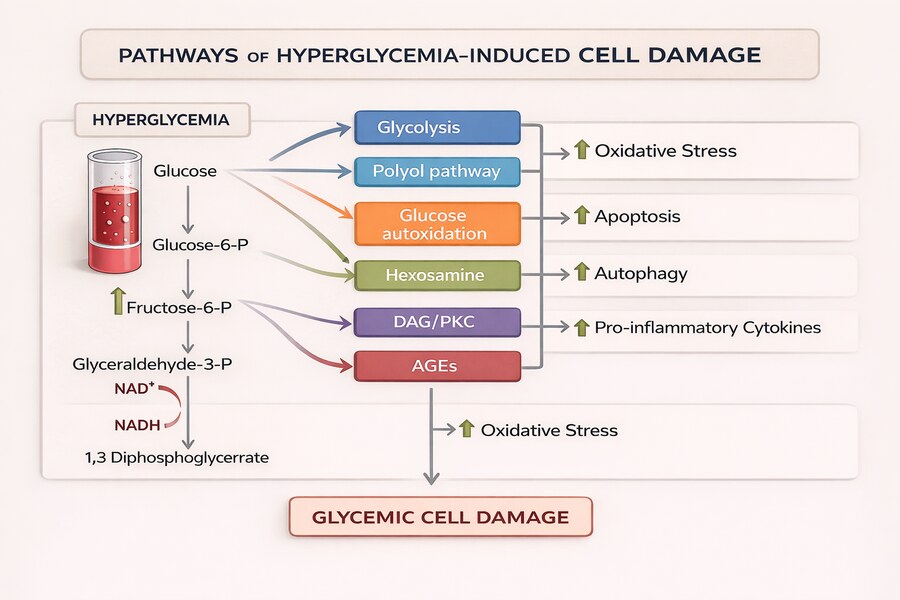

Glucose is a uniquely powerful fuel, but even beneficial things become harmful in excess. Too little glucose compromises brain and red blood cell function; too much damages tissues. Because of this, blood glucose must be maintained within a narrow “Goldilocks” range — not too low, not too high. The body’s entire fuel system is organized around this constraint.

This sensitivity to glucose exposure is not theoretical. Large population studies show that long-term blood sugar levels predict disease risk even below the threshold for diabetes. In one major analysis, individuals with glycated hemoglobin levels between 5.5 and 6.0 percent—still considered non-diabetic—had nearly double the risk of developing diabetes and a significantly higher risk of cardiovascular disease compared to those with lower levels. Importantly, these associations remained strong even after accounting for fasting glucose, suggesting that chronic glucose exposure, not isolated spikes, is what drives long-term damage.

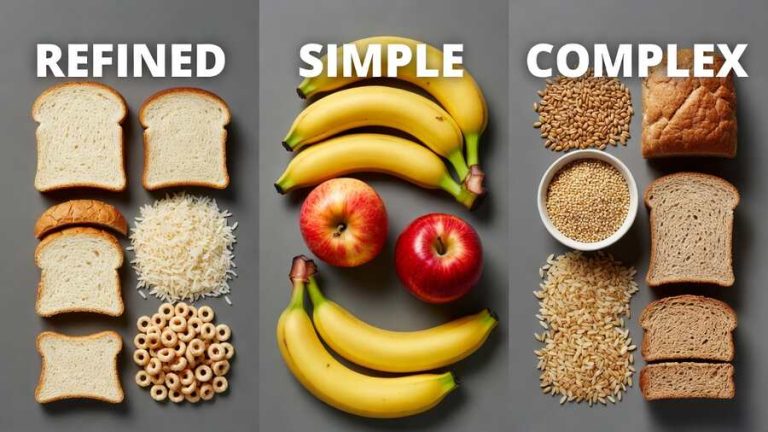

At a high level, the body prioritizes fuels in the following order:

- Glucose (circulating blood sugar)

- Glycogen (stored glucose)

- Fat (dietary and stored)

- Ketones (fat-derived fuel under low-glucose conditions)

This is not a hierarchy of “better” or “worse” fuels. It is a risk-management system.

Glucose is addressed first because it must be controlled precisely. Glycogen follows because glucose storage capacity is limited and exists primarily to buffer short-term fluctuations in blood sugar. Fat is deprioritized because it is stable, energy-dense, and safe to store in large amounts without disrupting blood chemistry. Ketones appear only when glucose availability and insulin signaling fall low enough that fat becomes the dominant energy source.

This hierarchy governs whether the body burns glucose or fat at any given moment. It explains why glucose is cleared first, why fat is stored so readily, and why shifting between fuels depends on specific metabolic conditions rather than dietary intent.

With this framework in place, we can now walk through the hierarchy step by step — beginning with glucose, the most tightly regulated fuel in the human body.

The Fuel Hierarchy

| Fuel | Primary Role | Speed of Availability | Storage Capacity | Main Risk if Overused |

| Glucose | Immediate energy & signaling | Very fast | Very limited (blood) | Tissue damage, inflammation |

| Glycogen | Short-term glucose stability | Fast | Limited | Depletion → instability |

| Fat | Long-term energy storage | Slow | Very large | Over-storage if unused |

| Ketones | Extended fat-based fuel | Conditional | Produced as needed | None inherently (context-dependent) |

Glucose — The First Fuel to Be Cleared

Glucose sits at the top of the fuel hierarchy for a simple reason: it’s the most tightly controlled fuel in the human body.

It’s also a uniquely powerful one. Glucose is fast, versatile, and essential — but even beneficial things become harmful when they fall outside their safe range. Too little glucose compromises brain and red blood cell function; too much damages tissues. Because of this, blood glucose has to be kept within a narrow “Goldilocks” zone — not too low, not too high. The body’s entire fuel system is organized around maintaining that balance.

Unlike fat, glucose circulates directly in the bloodstream. That makes it immediately available to tissues, but it also means any rise or fall affects the whole body at once. As a result, even modest changes in blood glucose trigger a coordinated response.

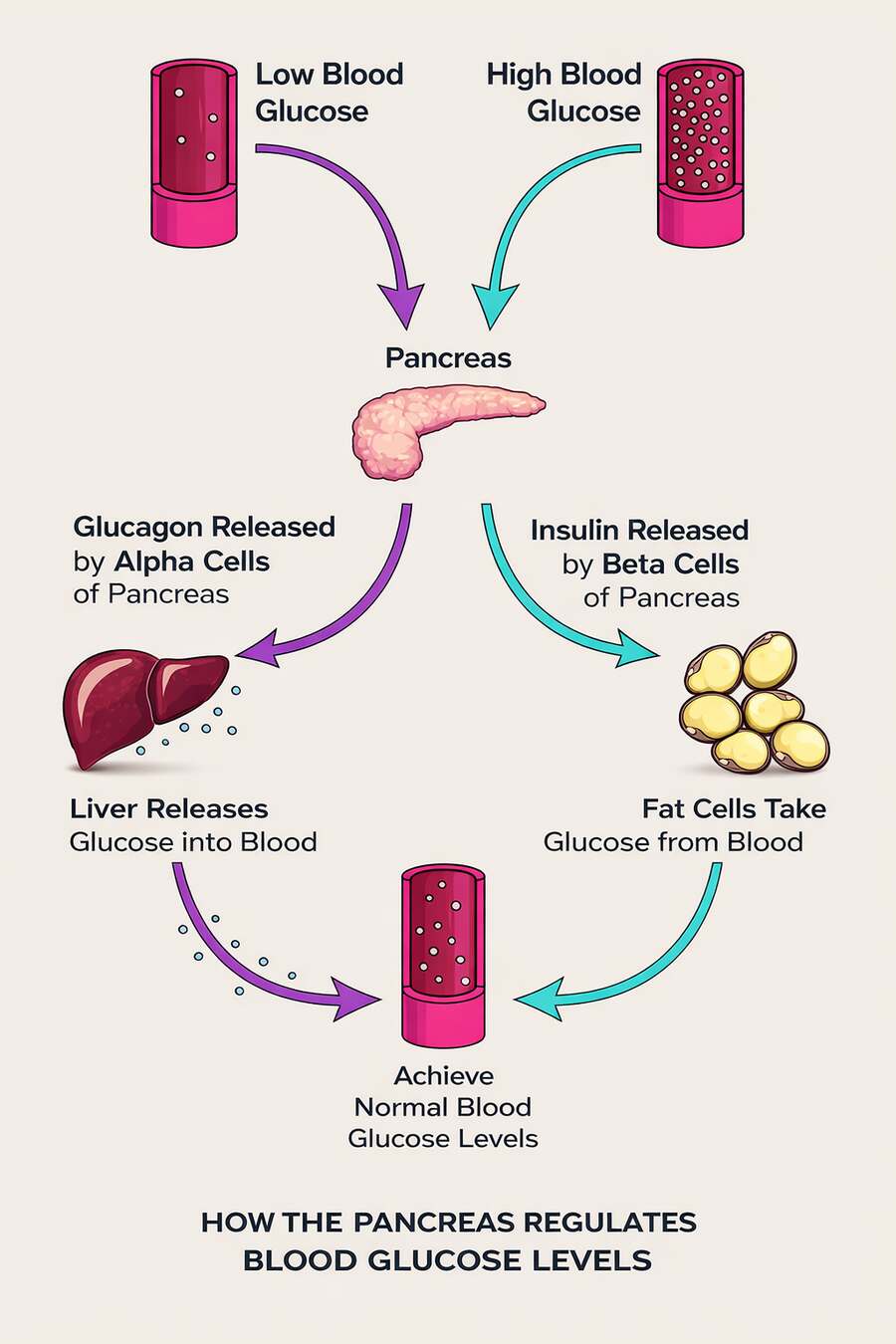

When glucose enters the bloodstream, sensors detect the shift and hormonal signals quickly come into play. Insulin is central here, signaling that glucose is available and helping direct it where it’s needed. Some tissues use glucose continuously, while others are more flexible and can switch between fuels depending on the situation.

For an in-depth look at exactly what insulin does in the body and how its so central to metabolic health, see this article here.

The goal in this moment isn’t to get rid of glucose — it’s to keep it under control. Excess glucose is routed into structured pathways: used for energy where appropriate, stored temporarily, or converted for longer-term storage. All of this happens with one priority in mind: returning blood glucose to its safe range.

It’s also important to understand that blood glucose doesn’t come only from food. Even when you haven’t eaten carbohydrates, your body still maintains glucose availability. It can release glucose from stored glycogen, and it can produce new glucose through a process called gluconeogenesis, primarily in the liver.

For a full look at exactly what happens when you significantly reduce carbohydrate intake, see this article here.

These production pathways are regulated just as carefully as glucose uptake. Insulin acts as a brake when glucose is abundant, suppressing both glycogen breakdown and gluconeogenesis. Other signals — including glucagon, stress hormones, and simple energy demand — push glucose production in the opposite direction when supply runs low. Together, these systems keep glucose available without letting levels drift too far in either direction.

This is why glucose is always addressed first when multiple fuels are present. Clearing glucose doesn’t mean burning it recklessly; it means bringing it back into balance. Once that’s done, the body has room to make longer-term energy decisions without risking instability.

From there, the hierarchy moves on to its short-term buffer: glycogen.

Glycogen — The Short-Term Buffer

Once blood glucose has been brought back into its safe range, the body still faces an ongoing problem: glucose must remain stable even as food intake and energy demand change.

Meals are intermittent. Activity is unpredictable. Yet certain tissues require a continuous supply of glucose, and blood levels cannot be allowed to rise or fall sharply in response to every change. Relying on immediate food intake alone would make glucose availability erratic, while switching straight to fat-based fuels would be too slow and too disruptive.

This is the problem glycogen exists to solve.

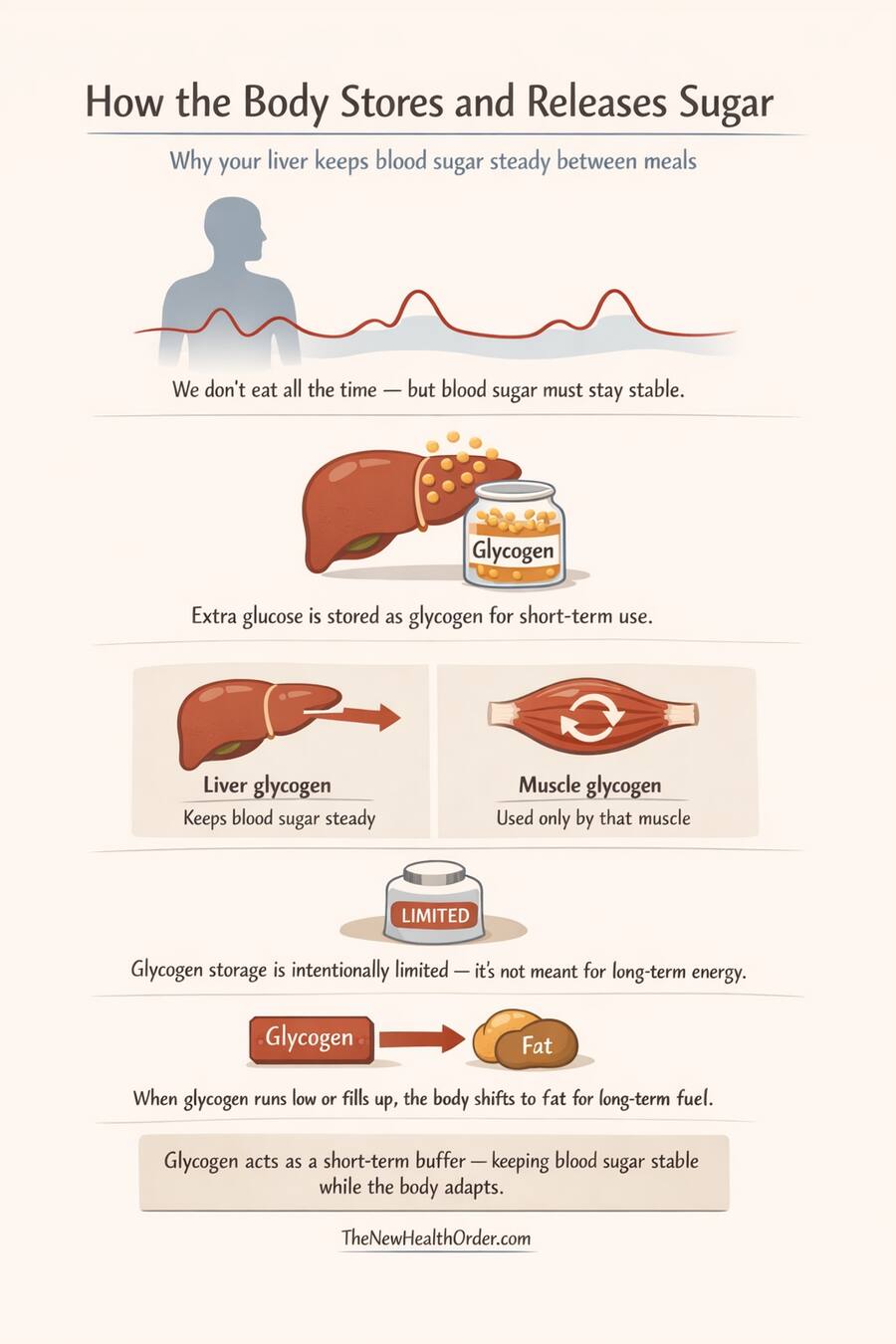

Glycogen is the stored form of glucose, held primarily in the liver and muscles. Rather than allowing excess glucose to linger in the bloodstream, the body converts it into glycogen, creating a short-term reserve that can be accessed quickly when needed. This allows blood glucose to be stabilized in real time, without forcing an immediate shift to longer-term fuel sources.

The liver plays a central role here. Liver glycogen is specifically dedicated to maintaining blood glucose for the body as a whole. When blood glucose begins to fall, the liver can release glucose within minutes, smoothing the gap between meals or periods of increased demand. Muscle glycogen, by contrast, is reserved for local use and cannot be shared with the bloodstream.

Importantly, glycogen storage is intentionally limited. The liver can store only a modest amount, and even combined with muscle glycogen, total capacity is small compared to fat stores. This limitation is not a flaw. It prevents the body from treating glucose as a long-term storage fuel and ensures that excess energy is eventually routed elsewhere.

Glycogen therefore acts as a temporal stabilizer. It decouples blood glucose availability from immediate food intake, buying time before deeper metabolic changes are required. It allows the body to maintain glucose stability without prematurely committing to fat-dominant or ketone-dominant states.

When glycogen stores begin to fill, excess energy can no longer be held safely as glucose. When glycogen stores are depleted, the body cannot rely on glucose buffering alone. In both cases, the hierarchy moves forward.

At that point, short-term stabilization gives way to long-term energy management — and the body turns to fat.

Fat — The Long-Term Storage Solution

Once short-term glucose stability has been handled, the body still has a bigger question to answer: what to do with the surplus energy that isn’t needed right now.

Glucose and glycogen can’t solve this problem. Blood glucose has to remain tightly controlled, and glycogen storage is intentionally limited. Neither is suitable for holding large or sustained energy surpluses. At that point, the body needs a storage system designed for capacity rather than speed.

That system is fat.

Fat is used for long-term energy storage because it does what glucose cannot. It is highly energy-dense, chemically stable, and safe to store in large amounts. Unlike glucose, fat does not need to circulate in the bloodstream, and storing more of it does not destabilize blood chemistry. From a regulatory standpoint, it is the least risky place to put excess energy.

Contrary to what many believe, fat storage is not a sign that regulation has failed. It is what happens after regulation has succeeded.

Energy enters the system, blood glucose is stabilized, short-term needs are buffered through glycogen, and only then is surplus energy committed to fat. In that sense, fat storage is the end point of energy handling, not the starting point.

Fat is also slow by design. Releasing and burning fat requires specific hormonal conditions and time. That slowness is often portrayed as a disadvantage, but it’s precisely what makes fat reliable. It prevents rapid swings in energy availability and allows the body to maintain substantial reserves without constant turnover.

This system covers all bases – glucose is managed minute by minute, glycogen smooths fluctuations over hours, and fat supports energy needs over days, weeks, or longer.

Without fat, long-term survival would be impossible. Periods of low intake, illness, or sustained demand would quickly become life-threatening.

But storing fat and using fat are not the same thing. Even when fat reserves are abundant, the body does not automatically burn them. Whether fat is accessed depends on the same hierarchy and signaling rules already in place. As long as glucose and glycogen are available, fat tends to remain in reserve.

Which brings us to the next step in the story: when, and under what conditions, does the body shift from storing fat to burning it?

Fuel Use Across Time Scales

| Time Scale | Dominant Fuel | What the Body Is Solving |

| Minutes | Glucose | Immediate energy & stability |

| Hours | Glycogen | Between meals, short gaps |

| Days–Weeks | Fat | Sustained energy availability |

| Prolonged low glucose | Ketones | Reduced glucose dependence |

When and How the Body Shifts Toward Fat Burning

Fat burning does not begin at a single moment, and it does not require an all-or-nothing metabolic switch. It emerges gradually, as the signals that prioritize glucose and glycogen begin to weaken.

The first thing to understand is that the body is always burning a mix of fuels. Even in a fed state, some fat is being oxidized. The question is not whether fat is burned, but how much of total energy demand it supplies at any given time.

That balance shifts as short-term fuels are drawn down.

After a meal, blood glucose rises and insulin increases. Under these conditions, glucose use is favored, glycogen stores are replenished, and fat release from storage is restrained. As digestion ends and glucose input slows, insulin levels begin to fall. This removes the brake on fat mobilization, allowing fatty acids to enter circulation.

Glycogen bridges this transition. Liver glycogen typically supports blood glucose for several hours between meals, depending on liver size, prior intake, activity level, and metabolic health. As liver glycogen is gradually depleted, reliance on fat oxidation increases in parallel. There is no abrupt handoff — fat use ramps up as glycogen contribution tapers down.

In practical terms, fat burning begins to rise meaningfully within a few hours after eating, and continues to increase overnight as glycogen stores are drawn down further. By morning, most people are already relying heavily on fat for energy, even if they consume a carbohydrate-rich diet.

This process varies substantially between individuals.

People who are metabolically flexible — meaning their tissues respond efficiently to insulin and can switch fuels easily — tend to transition smoothly. They suppress fat use when glucose is abundant and increase it quickly as glucose availability falls. In these individuals, overnight fat oxidation can be substantial.

Those who are metabolically inflexible experience a narrower operating range. Fat release may be slower, insulin levels may remain elevated longer, and the shift toward fat burning can be delayed or blunted. In these cases, the body remains more dependent on glucose even as availability declines.

Dietary context also matters, but not in absolute terms. Someone following a low-carbohydrate or ketogenic diet often spends more time in a low-insulin state, which lowers the threshold for fat release and increases baseline fat oxidation — including overnight. That does not mean fat burning is “on” all the time; it means the system is biased toward it.

At the same time, people eating higher-carbohydrate diets still burn fat regularly. Whenever energy expenditure exceeds intake — during fasting, between meals, overnight, or during prolonged activity — fat oxidation increases. This is true regardless of macronutrient composition. Fat burning is governed by energy balance and hormonal context, not dietary labels.

What changes across diets and metabolic states is how easily and how completely the body can shift its fuel mix.

As glucose and glycogen availability continue to fall, fat can become the dominant fuel source. When that dominance is sustained, the body may extend fat use further by producing ketones — not as a replacement for fat oxidation, but as a way to support tissues that cannot rely on fatty acids alone.

That final adaptation completes the hierarchy.

Ketones — Completing the Hierarchy

Ketones are not a separate or special fuel system. They are the final extension of fat-based energy use when glucose availability remains low for long enough.

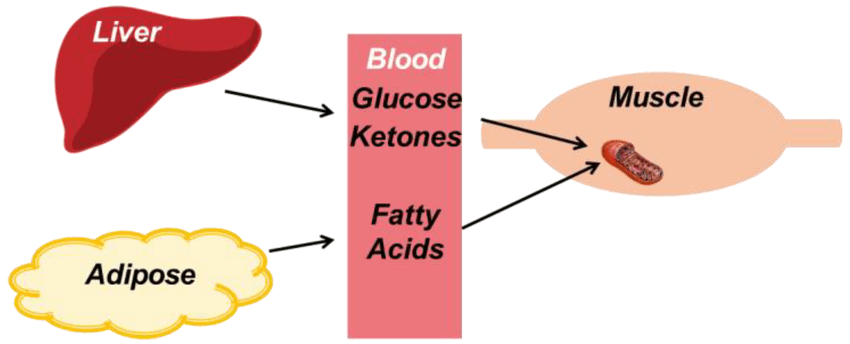

When fat burning increases, most tissues can meet their energy needs directly by oxidizing fatty acids. However, not all tissues can rely on fat in this way. Fatty acids do not cross the blood–brain barrier efficiently, and some cells require a water-soluble fuel that can circulate easily.

This is where ketones come in.

Ketones are produced in the liver from fat when glucose availability is low and insulin signaling remains suppressed. They act as a portable, fat-derived fuel, allowing energy stored in fat to be delivered to tissues that cannot use fatty acids directly.

Importantly, ketone production does not begin the moment carbohydrate intake drops or fat burning increases. It emerges after short-term glucose needs have been met, glycogen buffering has been drawn down, and fat oxidation has become dominant. In that sense, ketones sit at the bottom of the fuel hierarchy — not because they are inferior, but because they are conditional.

Ketones reduce the body’s dependence on glucose, but they do not eliminate it. Even in sustained ketosis, some glucose is still required, and the liver continues to produce it through gluconeogenesis. Ketones are therefore a supporting fuel, not a replacement for glucose metabolism.

This shift becomes especially clear when looking at the brain’s energy demands. Under normal glucose-dependent conditions, the brain requires roughly 120 grams of glucose per day. During sustained fat-based metabolism, however, this requirement drops dramatically—to approximately 30–40 grams per day—as ketones begin supplying a large portion of the brain’s energy needs. This reduction is not incidental. By lowering glucose demand, ketones spare muscle protein that would otherwise be broken down to support gluconeogenesis, allowing the body to maintain energy availability without sacrificing lean tissue.

This distinction matters. Ketosis is often framed as a dramatic metabolic switch, but in reality it is an adaptive extension of an existing process. The body does not “enter ketosis” as a goal; ketone production increases because conditions make it useful.

Like fat burning itself, ketone use varies widely between individuals. People who are metabolically flexible tend to produce and use ketones more readily when glucose availability is low. Others may require more prolonged or consistent conditions before ketone levels rise meaningfully.

Seen in context, ketones are neither exotic nor extreme. They are part of the same coordinated system that governs glucose, glycogen, and fat — activated only when earlier layers of the hierarchy are no longer sufficient.

With the hierarchy complete, the final question becomes less about which fuel is being used, and more about how easily the body can move between them.

Fuel Hierarchy and Metabolic Health

Understanding the fuel hierarchy changes how you see modern health problems.

In theory, glucose and fat are both essential fuels. In practice, however, most people spend nearly all their time in glucose-dominant mode. Meals are frequent, carbohydrates are constant, insulin rarely falls, and the body is almost never allowed to move beyond the top layers of the hierarchy.

See this article here for a more in-depth look at what is happening to your body when you constantly rely on carbohydrates for fuel.

The result is not just impaired fat burning — it is a persistent inflammatory state.

Glucose-dominant metabolism is not inherently harmful. It becomes harmful when it is uninterrupted. When insulin remains chronically elevated and glucose is always available, the signals that support repair, recycling, and cellular housekeeping are consistently suppressed. The body stays in a fed, growth-oriented state, even when no growth is required.

Fat- and ketone-dominant states are different. They are associated with lower insulin signaling, reduced inflammatory tone, and a shift away from constant storage toward maintenance and repair. This does not mean glucose is “bad,” but it does mean that never leaving glucose mode comes at a cost.

Many modern metabolic issues make more sense through this lens. Chronic inflammation, poor metabolic resilience, unstable energy, and impaired recovery are not necessarily caused by eating the wrong foods, but by never giving the system a reason to transition.

In a healthy metabolism, fuel use changes naturally over time. Glucose rises and falls. Glycogen is filled and drawn down. Fat is stored and accessed. Ketones appear when conditions persist. The system breathes.

In a metabolically rigid system, it does not.

This is why metabolic health is less about maximizing one fuel and more about restoring range. A healthy system can use glucose when it is abundant, then move away from it without stress. It can tolerate periods of lower intake, lower insulin, and deeper reliance on stored energy without triggering dysfunction.

For the reader, the takeaway is not a diet rule, but a question:

Does your metabolism ever get the chance to move down the hierarchy — or is it kept permanently at the top?

You do not need to fear glucose. But you may need to reconsider how often you keep your body in a state that never allows the deeper layers of metabolism — fat use, ketone production, and repair-oriented signaling — to engage.

From here, the most important shift is not what you eat, but how much metabolic contrast your body experiences. Long stretches of constant intake, constant insulin, and constant glucose demand keep the system locked in one mode. Creating space — whether through time, activity, or structure — allows the hierarchy to function as intended.

Once you see metabolism this way, many debates lose their force. Fat storage stops looking like failure. Ketones stop looking extreme. And glucose stops looking like the only fuel the body knows how to use.

What matters most is whether your metabolism still remembers how to change gears.

FAQs

How does the body decide whether to burn glucose or fat?

The body prioritizes fuel use based on glucose availability and insulin signaling. When blood glucose is high and insulin is elevated, glucose is used first and fat release is restrained. As glucose availability declines and insulin falls, fatty acids are released from storage and fat oxidation increases. This shift is gradual, not binary, and both fuels are often used simultaneously in different proportions.

Does burning fat mean you are in ketosis?

No. Fat burning and ketosis are related but distinct processes. Fat oxidation begins as soon as insulin levels drop and fatty acids are released, which happens daily between meals and overnight. Ketosis occurs only when fat oxidation is sustained and glucose availability remains low long enough that the liver begins producing ketones to support tissues that cannot use fatty acids directly.

Why does the body make ketones instead of just producing more glucose?

Relying entirely on glucose produced through gluconeogenesis would be metabolically costly and would increase protein breakdown from muscle tissue. Ketones allow the body to deliver fat-derived energy in a water-soluble form, especially to the brain, while reducing glucose demand and sparing lean tissue. Ketone production is therefore a protective adaptation, not a replacement for glucose metabolism.